About this episode

Zetta Elliott (Dragons in a Bag series) shares how her experience growing up Black in suburban Canada impacted her reading, and ultimately her writing voice. She'll tell us about discovering her heritage, finding her voice, and disrupting the world of children's literature.

"When you're a kid, and if you love to read, you love stories, you aren't always aware of the fact that you're being erased from those stories, or you don't yet have the expectation that you should be in those books." - Zetta Elliott

Zetta Elliott knows the damage being left out of the stories you consume as a kid can have. Growing up Black in suburban Canada in the 80s meant rarely having the opportunity to see herself in her reading. It wasn't until she was a young adult that she realized this erasure's impact on her voice as a writer.

While she is best known for her Dragons in a Bag series, Elliott has had a full career fighting for fairness and representation in children's literature. She tells us about how she found and reclaimed her voice and her struggles with publishing as a Black author.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - Getting to Know Zetta Elliott (2:02)

- Chapter 2 - Being Left Out of Literature (5:50)

- Chapter 3 - Zetta Finds Her Voice (10:46)

- Chapter 4 - Won't You Celebrate With Me? (14:49)

- Chapter 5 - Self-Publishing (18:03)

- Chapter 6 - The Future Depends on Now (23:15)

- Chapter 7 - Beanstack Featured Librarian (27:10)

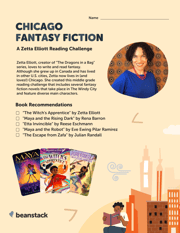

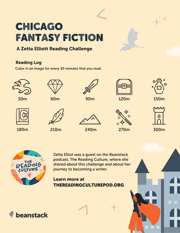

Zetta's Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

Zetta Elliott: I do hope that more and more kids are seeing themselves. But you know, it all depends on who green-lights the projects. And we haven't made much progress in terms of diversifying the professionals that work in publishing. So until we do that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Representation in children's literature is a matter of life and death. That's what Zetta Elliot wrote in a 2009 blog post where she advocated for the industry to take the issue seriously. She knows personally how isolating it is to not see yourself in the books you read as a kid and the impact that can have long term.

Zetta Elliott: There are times when I write something, or even with poetry, I write something, I'm like, God, that's so formal. Like, why is that so formal? I'm like, Oh, it sounds British. Why does it sound British? It's like, Well, what were you reading? You know, what were you feeding your imagination for all those years when you were in your formative stages?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Zetta is a children's author, a poet, an essayist, and an advocate for diverse representation in the publishing industry. She's perhaps best known for her 2008 book Bird and more recently for her Dragons in a Bag series. In this episode of the Reading Culture, Zetta shares her story about growing up Black in suburban Canada and how that experience sent her on a journey to rediscover her heritage, find her voice, and write for children what she wishes she had for herself. And stick around at the end to hear about Zetta's reading challenge for you and how you can participate. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is the Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Today we're joined by Zetta Elliot.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: One thing I was really struck by when I went to your website, Zetta, was that the first thing I saw were all these pictures of your family and your history, and I think it's unusual for... And telling. So I thought I'd maybe ask you first to just talk about the importance of connecting your history and your past to your present. That seems like something that's really important to you.

Zetta Elliott: That is, what a fantastic question. So if I were to open the door of my office in the hallway, I always have in every apartment I live in an ancestor wall and I am really fortunate that I seem to be the designated, person in my family who gets all the best photos. And so somebody will dig up an old Black and white photo of a great, great, great grandparent and they'll send it to me. So I have this amazing collection of photographs and when it came time to design my website, I didn't want a whole lot of pictures of me. I think I had just had my first photo shoot and was like sort of horrified by the results and just thought, you know, I do write a lot about history, about ancestry. I very much wanna make the past feel present and to feel relevant to young readers.

Zetta Elliott: It feels very relevant to me. I think about my ancestors a lot and because I do walk past a wall of them every single day, I'm very aware of sort of the debt that I owe and how much they sacrificed and how different their lives and their dreams were from mine. My grandmother, my maternal grandmother, was deeply invested in genealogy because she believed herself to be a descendant of Bishop Richard Allen of one of his brothers, really, who left the Philadelphia area and came to Canada probably in the 1830s and settle on some land and sort of became committed to integration, which meant they intermarried deliberately and then they weren't trying to pass for white, but they stopped talking about their Black ancestry because...

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Oh my God, it's like the vanishing half like...

Zetta Elliott: Basically like you know, like if you thought you were descended from a bishop, one of the most significant Black figures in the US you'd probably be talking about that a lot. But in my grandmother's family there was sort of this pact that said, we're not gonna talk about it. And so, you know, my great-grandfather, he always checked colored. I mean nobody was saying we're white. But over a couple of generations they started to look white. So even my mother, you know, my mother is technically an Octa Roon, so she's one-eighth Black, but she presents as white, identifies as white. Her mother, my grandmother was a Quad roon presented as white, but identified as negro. So it's kind of this complicated history, but also one that's marked by silence and shame. And it's so interesting 'cause people will say, Oh, your ancestors must be so proud. And I'm like, some of them, not all of them, it's a few of them who wish, you know, my mother hadn't brought Blackness back into the family by marrying an Afro-Caribbean man. But it's a complicated history and I think I feel so grateful that my grandmother, you know, said to her father, I'm not gonna be quiet.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I think it's so interesting you have these really strong connections to your past because, you oftentimes like refer to yourself and you are like a futurist, you know, and you're writing about the, like all, a lot of your work is, that it's always like bringing the past into the future, which I think is a pretty fascinating thing.

Zetta Elliott: Yeah, I think a lot of people, you know, are so enamored with Afrofuturism and I don't always feel like I belong because I do tend to be backward looking. But that is part of Afrofuturism is that you look back in order to go forward, which is also the Sankofa principle. And so yeah, you can't build a future if you haven't understood how the foundation we're standing on was built. So yeah, it's important.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Zetta's journey to rediscovering her history is one that she's deeply committed to. In her early young adult years she made the bold decision to move away from her childhood home in search of a more genuine connection to her community and her roots. Zetta grew up partly in a small town outside Toronto, Canada named Pickering, and partly in a Toronto suburb named Scarborough. But while Canada provided a safe and stable life, Zetta was finding it difficult to connect to her identity as a Black girl. As she reached adulthood, she began to understand what had been missing from her reading experiences in her youth and how that impacted her voice.

Zetta Elliott: I felt pretty blessed to grow up in Pickering, again, I think because my parents were teachers, that was definitely an advantage. My mother loved Ezra Jack Keats. I think if she hadn't, I wouldn't have had any books with Black characters. So because she used those books in her classroom, I had those... Exposure to those books in the classroom as well. There was nothing at the library that had Black children in it, I mean, just nothing. And I remember reading books that were really old, like from the 1930s, maybe 1940s, 1950s. And of course, they seemed new to me, but they were, it was sort of Dick and Jane, little blonde hair, blue eye children with lollipops. Like it was really sort of this kind of vintage children's literature and lots of books about animals. And then because Canada's a British... Former British colony, there was a lot of British content that I was reading as well.

Zetta Elliott: When you're a kid and if you love to read, you love stories, you aren't always aware of the fact that you're being erased from those stories or you don't yet have the expectation that you should be in those books. So I think I did have kind of a golden era of reading where I just loved to read and I would read anything that I could get my hands on. And then maybe by the time I was 10 I started to notice that there was a problem and that when I went to the library, the public library, the librarian would pick a book, you know, by Virginia Hamilton or Walter Dean Meyers and sort of be like, You should read this. And then I resented, you know, being handed a book with some weird 1970s Black kid on the cover and you know, why is she giving this to me.

Zetta Elliott: And you know, I read the Bronte's. So yeah, it was so messed up. But by the time I got to college, you know, university in Canada, then I was exposed to post-colonial literature and Jamaica Kincaid and Tony Morrison. And then you start to understand that there's this whole other storytelling tradition, of which you can participate and appreciate and well, that's when you get angry. 'Cause then you're like, there are all these other books out there, right? Like, What was wrong with my library? What was wrong with my school? What was wrong with my parents? Like, why, why wasn't I given these options? And then you blame yourself because I chose to study British Victorian poetry. I could have been studying something else.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Did you always wanna write, by the way, was that a thing that you liked doing when you were younger? Were you always...

Zetta Elliott: I liked stories and I liked storytelling. I didn't... I wrote... You wrote for school, right? 'Cause you had to, but I wouldn't have been writing at home until I was a teenager. And then I had an English teacher that said, You could be a writer. But up until then, I just... I liked having an audience. So if you're a good storyteller, you can get an audience in the schoolyard. So I learned to tell stories that way.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Do you remember any of the ones that you told?

Zetta Elliott: Absolutely, because it was all ripped from the headlines of my life and my parents had divorced and my father... My parents both grew up in the Pilgrim Holiness Church. So, you know, girls can't wear pants and no secular music. It was pretty extreme. And then, you know, my dad sort of like discovered RnB and he had like a Black power moment and then he went back to his Black girlfriend from, you know, high school. So it got really complicated really quickly. And then my mom sued for divorce.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: How old were you when that happened?

Zetta Elliott: Seven or eight. So that's one of the reasons, I often write about kids who are 7, 8, 9, 10 years old is that was a really kind of hectic moment for me. And that's when storytelling kicked into full mode because you know, we had to go spend weekends with my dad and it was just chaos. It was almost always chaos. And he would be introducing people that I did not want in my life and I would be confronting them and then I would be confronting him. And I had been a daddy's girl and so then suddenly he saw me as disloyal. And so yeah, I, you know, every Monday kids would be like, Ooh, how was your weekend? 'Cause you know, these were white middle-class kids.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Like gather around the Zetta campfire.

Zetta Elliott: Basically. Basically.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: We're about to hear some stories.

Zetta Elliott: Have some Black pathology for your entertainment. So yeah, looking back on it, I wish I maybe hadn't embellished as much as I did, but I didn't have to embellish much because it was crazy.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Like a lot of young creatives searching for culture and opportunity, Zetta was drawn to New York City. Even as a kid, she felt the the power of its community.

Zetta Elliott: I went to New York when I was I think six and was like, whoa, this is a lot. And that was my first majority-Black environment.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: New York is where as an adult, Zetta would find her craft, her voice and the stories she wanted to tell. But finding that voice was something she would struggle with for a long time. She had a lot of unlearning to do about the world of literature she had been exposed to, the world of literature that nearly erased her and her identity.

Zetta Elliott: It's a strange thing to sort of grapple with your own hybridity and to say, I wanna write like Dickens and then realize Dickens had no great love for Black people and so why are you trying to sound like someone who doesn't actually have much respect or interest in you and your history and your communities and grappling with the history of colonialism and sharing my writing with a friend for the first time. She's from Detroit, this Black woman, and she's like, Oh my god, you sound so British. And you know, five years earlier that would've been the hugest compliment. And then I was just like mortified and like, oh my God, I sound British, what am I gonna do? And so trying to sound like an African American from Georgia, I am not an African American from Georgia, so.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: What did you do?

Zetta Elliott: Well, Jane Cortez has this great poem where she says, find your own voice and use it. Use your own voice and find it. And I think that's really sort of just what you have to do is write your way through it. Just keep writing and writing and writing and then read it out loud and listen to yourself and see if you hear your actual authentic voice. It is, it takes a long, long time. There are still moments... I'm working on book five of the Dragon series right now and there are times when I write something or even with poetry, I write something, I'm like, God, that's so formal. Like why is that so formal? I'm like, Oh it sounds British, why does it sound British? It's like, well what were you reading? You know, what were you feeding your imagination for all those years when you were in your formative stages? So I can't uproot all of those early influences, but I can at the very least be aware of them and then engage them in some ways, if not erase them.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: What do you think about kids today who are similarly, like how you are coming from these varieties of backgrounds and growing up in this world. Do you think that it seems like children's literature and the world around us has made that, an easier thing to accept and to like fully understand and self realize earlier for kids who are hybrids or mixed?

Zetta Elliott: We're not there yet, but it's certainly a whole lot better. We're definitely not there yet. We have so many realities that are not being represented and publishing tends to go for whatever sells. So they'll get one narrative and stick with it and then they want 20 more examples of that. So it can be pretty difficult to find really original intersectional identities in children's literature still. But I have to say, every once in a while I look and see what's on Netflix and holy cow, like I could never have seen any kind of fantasy film that had so many kids of color in it. And sometimes they're the star of the... Like that's just incredible to me. And there are generation, you know, a whole generation of kids, that's all they know. They would never go back to a film that had an entirely white cast, which was all I had growing up, right. And you prayed, there might be a Billy D. Williams or somebody who got to come on screen and do something besides die.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Like just looking for that one.

Zetta Elliott: The one please and let them live to the end of the film. So, so yeah, I do think in other forms of entertainment we're doing better. Literature, like I said, it's been slow and it may not last. We tend to get these sort of peaks and then they plateau and we go back to the standard traditional representations.

Zetta Elliott: Won't you celebrate with me what I have shaped into a kind of life? I had no model, born in Babylon, both non-white and woman. What did I see to be except myself? I made it up, here on this bridge between star shine and clay, my one hand holding tight, my other hand, come celebrate with me that every day something has tried to kill me and has failed.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: That poem was called Won't You Celebrate With Me by Lucille Clifton from her 1993 book, Book of Light. Clifton was a Black poet and two-time Pulitzer finalist from New York State. Like Zetta, Lucille Clifton was dedicated to discovering her own heritage and forging her way as a proud Black writer. The poem is one that has inspired Zetta immensely throughout her life.

Zetta Elliott: So that's a poem that gets circulated quite a lot. It means a lot to a lot of people, but it's just so brilliant because it feels so true. There's that moment in all of us where we think I wanna be X, but if you haven't actually seen someone else do it, you're not sure that you can. Right? Who did I see to be except myself? So when I was struggling with finding my voice and wanting to be a writer and then all of a sudden I discovered there were all these Black women for centuries who had been telling stories and who had been making art. And then you just realized you're not alone. So even though you're human, I love her reference. You know, we're star-shine in clays, so we're humans.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I saw you reference that too in your other... In one of your poems, right?

Zetta Elliott: I do. Right. So then I'm, you know, riffing off of this poem because there are so many ways in which it echoes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I love that, it's like you're in conversation with all these other poems that are in your book.

Zetta Elliott: It's like sampling. I try to explain that to kids. It's like signifying is a big part of the Black vernacular tradition and it's, you can see it in hip hop, right? And so a lot of times those younger kids, they don't know what the sample is, but we know the original track that's being sampled. And so anyone who knows Lucille's Clifton's poetry will hear the echo of it in some of my work. And I am just so grateful. It's an opportunity for us to look back and say, how did we deal with this in the past? Because we've always dealt with this for Black women, you know, other people trying to control our bodies, that's nothing new. So we have a lot to learn from our ancestors and they left us the blueprint. So we just have to honor it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: You know, hearing you speak about Lucille Clifton and bringing her poetry into your beautiful poetry book, Say Her Name, which we were just discussing, it almost feels like you're building your own written ancestor wall.

Zetta Elliott: Absolutely. Like they're like beacons, right? They're the light. When you're floundering around, you can look across the sea and be like, Oh, somebody found land and they're over there sending me a signal and if I can just get over there, maybe I'll be okay too.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: A theme you'll notice in Zetta's story is pushing through when the world around her is full of barriers. She fought for her heritage, her voice, and she continues to fight for that voice to be heard. Dragons in a Bag is her breakthrough series, but Zetta has been writing children's stories for decades. So Zetta, in your early years as a writer, you had to self-publish because the publishing industry wasn't very receptive to your voice. Now you've won a Caldecott honor and you're in demand and that must be vindicating. So two questions for you here. First, are readers gonna see more of your early work now? And second, should we be celebrating this seeming reversal in the industry?

Zetta Elliott: A place inside of Me is a book that came out in 2020 and I wrote that 20 years ago. So there are still stories. If we can get an editor... Yeah, if we can get an editor to look at some of the stories I wrote when I started writing for kids in 2001, if we can even get them in front of an editor, sometimes they sell and then, you know, 20 years later.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Sometimes they win big awards.

Zetta Elliott: Like a Caldecott Honor, right? And it's just, it's really frustrating 'cause that I think people, because of the success of the Dragon Books, people think of me as sort of a new author and I'm like, Oh, new to you. [laughter] I've been doing this a very long time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Right. It's that old thing of like people who are like, overnight success, and you're like, no, it's not an overnight success.

Zetta Elliott: And it's what my professor used to call the problem of exemplarity. He was talking about Frederick Douglas. So Frederick Douglas is this enslaved individual who frees himself, teaches himself, he's self-educated. And then he writes this brilliant narrative and it ends up almost becoming used as a defense of slavery because it says, look, we have this system that produced a genius like Frederick Douglas. It's like, whoa, that is not what we're arguing for here, we're arguing for the abolition of slavery. But people look at my self-published books, especially the ones that are selling well and they'll say, well Zetta it's just wonderful the way that you turned, you know, lemons into lemonades and you made the best of a bad situation. It's like, no, I should not have had to self-publish 20 of my books.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: It shouldn't be that way. And how many people did we lose? Like how many people like were lost and didn't have that wherewithal or... It's not even wherewithal, who just didn't...

Zetta Elliott: Absolutely.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Couldn't for whatever reason, you know, continue and...

Zetta Elliott: We'll never know all the stories we've lost because they were rejected and the doors were closed so many times that somebody just said, it must be me, I'm not cut out for this.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: You've written a lot of stories in your career and seem to have a good understanding of what publishers are willing to work with and what they're not. Does this knowledge now inform your writing at all?

Zetta Elliott: So I would say if I have... I have 25 unpublished picture book manuscripts on my computer and I could divide that list of 25 into two piles and I know which ones I will absolutely have to self-publish because there is no way an editor working today is gonna acquire and publish that. They'll either see it is being, you know, do a cost-benefit analysis and say it's too niche or it's too sad or all these things that I hear, and then I could, you know, look at the other list, the other pile and say, I think these are really sellable. In fact, I think this is highly commercial. You know, we see a lot of books about animals and cute little animal stories being written by white men and they're best selling huge, hugely successful books, but it's never... Black people aren't allowed to tell those stories. So people will say to me, Oh, you write such, you know, heartfelt, serious stories about addiction and police brutality and I'm like, I write fart stories like I write all kinds of books, but you're seeing...

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I can be all of it.

Zetta Elliott: Is what gets through the gate. Yeah, you know, we could do everything. I think Phil Nell is a scholar, white male scholar based in Kansas and he said, you know, genre is the new Jim Crow riffing off of Michelle Alexander's book. And there's a way in which the door opens to say, okay, more Black authors, you can come in, but we still want you to write picture book biographies, historical fiction, realistic fiction about gun violence. And now they're expanding a little bit more to fantasy, but it needs to be African fantasy based on West African mythology. And so you still end up being very limited by what these white editors are curating, which is exactly what it is. It's curation. So you can't actually say that what has been traditionally published accurately reflects African American interests because those are simply the books that got green-lit. So if anybody wanted to see my full "range," they would have to look at the 40 books that I have published, two-thirds of which are self-published. And then you would really need to look at the self-published books to say, well that's what's getting rejected by the traditional publishing industry. You know, I do lamb and calf but butts. I bet I'm gonna have to self-publish that because I bet no editor is gonna want it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: In 2009, Zetta wrote a blog post titled something like an Open Letter to the Children's Publishing Industry. In it she pleaded with the industry to take the lack of representation in books seriously. She wrote, What I'm trying to say to children's publishers is that the lack of books for children in our communities is a matter of life and death. I'm not asking you to level the playing field as a favor to people of color. I'm asking you to work with us in our efforts to transform children's lives. Isn't that why you chose this field in the first place? 2009 is as of this recording 13 years ago. And while a lot of progress has been made since then, there's still a long way to go. Book bands and challenges, especially those targeting stories with Black and brown main characters are increasing and the politicization of libraries and the industry writ large is threatening the progress we've seen. Zetta has seen this battle ongoing for decades, most often at the front lines herself. I was curious about what she predicts for the future. I asked her if we were gonna continue to see doors open for diverse writers and characters and this is what she said.

Zetta Elliott: I wish I were that optimistic. I'm not. I think no, we're gonna... We have this blip and then it's gonna plateau. I think where I feel a bit more optimistic is in the technology that makes it possible for us to have other avenues to tell our stories. There is still a lot of stigma against self-publishing and it's still a huge challenge to get even independent bookstores that are, you know, trying to champion authors. You know, they often won't support Indie authors, so libraries won't Indie titles if they haven't been reviewed and Review Atlas won't review Indie titles. So we still have a lot of structures that need to be broken down, but in the midst of that, people are finding ways. I was at a book fest last month organized here by a bookstore owned by a Latina, Nina Sanchez and she, you know, pulled together 20, you know, self-published authors here in Chicago. We're everywhere. We don't get invited, we don't get asked to the table. And then she just created her own event. So that's fantastic. And I think if we start to see more of that and people realize you don't need a big record label to tell you what to listen to. You don't need a radio station to tell you what you listen to. Right. Kids don't even listen every... I don't even know if they listen to radio stations anymore.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: No, they're like listening to TikTok, which it's like kind of similar, right? Like they're listening to and then that's now those record labels are all like figuring out what's... What to do this way. So I guess that could be like a...

Zetta Elliott: Scrambling.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: That's right. But that could be like a foreshadowing of what's... Of what could, what is possible.

Zetta Elliott: It's that disruption, right? All we need is that kind of disruption that sets people to thinking, oh wow, we need to do things differently. And then people become aware that there are alternatives 'cause so many people don't even know that Black-authored books are published by Random House or Simon and Schuster or Harper Collins 'cause they don't market books to Black readers. And so if these kinds of book fairs and book festivals and Indie authors, if they can have a direct access to their own audience, then they don't need anyone to give them the stamp of approval or to open the gate or greenlight their project. And I think, I hope in 20 years, we'll be seeing more of that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: That again was Zetta Elliot, children's author, poet, and essayist. Zetta's Beanstack reading challenge is for middle-grade fantasy novels set in Chicago. You can learn more about that and how you can participate by visiting thereadingculturepod.com. Check it out and let us know what you think. And now it's time to celebrate this episode's Beanstack featured librarian. Today we have Kelly McDaniel, assistant director for the Piedmont Regional Library System in northeast Georgia. We had her spill her secrets on how she gets kids excited about reading.

Kelly McDaniel: I think the secret sauce to getting kids really excited about reading kind of contains three main points. I think enthusiasm is really important. I love to hear people speak about something that they are enthusiastic about. So I try to share with children what I'm reading, what I've enjoyed lately, what really excites me about books. I also think modeling is really important. I read, they see me reading. I want them to know that I read and we talk about books. The third trick is letting them quit. I heard about a two-chapter rule. As long as they're willing to read two chapters and then they decide they don't like the book, they can quit it and put it down and never read it ever, ever again. I really want children to read books that they like. I think that is what gets them hooked for life on reading. So if we can find something they like, great. If they get a little bit into it, decide they don't like it, they get to put it away forever.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: This has been the Reading Culture. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey. And currently, I'm reading Solito by Javier Zamora and the Inquisitor's Tale by Adam Gidwitz. If you enjoy today's show, please show some love and rates, subscribe and share the Reading Culture among your friends and networks. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script-edited by Josiah Lamberto Egan. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode of the show. Thanks for joining and keep reading.