About this episode

Author-illustrator Victoria Jamieson ("When Stars Are Scattered," "All's Faire in Middle School," "Roller Girl") talks to us about why she loves illustrations in literature, authors that inspired her, and how a dream job rejection inspired her first book.

"I think there's so much you can do. It's so rich because you have words, you have pictures. Sometimes they say the same things, sometimes they say opposite things. There's such an interplay between the two that I feel like there's so many possibilities." - Victoria Jamieson

Victoria Jamieson was always an introverted child, but a move across states in middle school pushed her further inward and made her grasp for familiarity. She quickly found comfort in the local library after her mother became the regular host of their summer reading program. While Victoria was an avid reader, burning through Ramona Quimby stories, she also found herself deeply interested in the Sunday comics in newspapers, and eventually comics such as Calvin and Hobbes.

This lifelong interest in artwork and storytelling would inspire her own career as an author-illustrator. But as Victoria discovered an additional gap in the comic industry for middle-grade literature, she was influenced to take a shot at writing her own graphic novel.

This episode's Beanstack featured librarian is John Henry Evans, a school librarian at Walter T. Helms Middle School at West Contra Costa Unified School District in California. Today, John Henry shares a moving story about a student, a book, and an unexpected post-it note.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - Owner of the library

- Chapter 2 - Ramona and Beezus

- Chapter 3 - From Ramona to Rollergirl

- Chapter 4 - Astrid, The Likable

- Chapter 5 - The allure of Lego manuals

- Chapter 6 - Omar’s Story

- Chapter 7 - Warm Welcomes

- Chapter 8 - Reading Challenge

- Chapter 9 - Beanstack Featured Librarian

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

View Transcript

Hide Transcript

Victoria Jamieson:

My son didn't want to read Ramona, but he loves instructional manuals. He loves reading books about math now. So I really had to live the words I'm saying to people, which is like, it doesn't matter what your kid is reading. I think if they cultivate a joy of reading, that's the most important thing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Graphic novels are often a point of contention among adults and kids' lives. Should we encourage them to read comics? Should we be concerned if they prefer graphic novels to traditional prose? To put it bluntly, pretty much any type of discouragement of reading is bad, but Victoria Jamieson takes the argument further than that. As a graphic novelist herself, she understands the unique value that this type of literature offers kids.

Victoria Jamieson:

One thing that makes me feel very connected to graphic novels is that feeling of being invited into somebody's house because in a graphic novel, I don't describe where they are, but I need to decide, okay, what does her house look like? What does her bedroom look like? What kind of posters are on her wall? So I always picture it like I'm just like peeking in through somebody's window and getting to see where they live.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Vicki is the creator of the beloved Newbery Honor book Roller Girl, the harrowing real life story told a National Book Award finalist, When Stars are Scattered and various other graphic novels and picture books. In this episode, she unpacks the underrecognized value of graphic novels in children's literature, the dream job rejection that inspired her to create Roller Girl and the delicate act of honestly presenting trauma in a story for kids. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. What were you like as a kid? Younger, first? Younger, then we can get to middle school, but elementary school age?

Victoria Jamieson:

Elementary school, I was very shy, very quiet. I think people just thought I didn't talk, especially in... In school, I had my best friend, so I always talked to my best friend. I felt like I was good with one friend. But when I went to family functions or was in larger groups, I was just very quiet.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Were you one of many siblings or just you?

Victoria Jamieson:

I have an older brother and a younger brother, so I'm the middle child, but I was the only girl, so I never felt like I had middle child syndrome. I always had plenty of attention, but I'd just always like to go off of my own imagination, I think. I had lots of stuffed toys that I played with and I was pretty content on my own to not be bothered by my brothers. I could just entertain myself for a good long time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And then so in middle school was sort of same thing, you were more to yourself or always had one or two good friends?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I think everything got exacerbated in middle school like it does for most kids. My family moved from Pennsylvania to Florida when I was in seventh grade. So I'd stayed in the same town up until then, so I knew everybody. We knew all our neighbors. I had my comfort, but we moved to a new state and everything totally changed. Everything I thought I knew about being cool or making friends just didn't work. And then I definitely... That's really when the shyness kicked in. I was just so embarrassed, so self-conscious, so afraid to talk to anybody. But as a kid, I read a ton. My mom took us to the library all the time. It was kind of our second home. She wasn't a certified librarian, but after a while, we went there for so long, she just started working at the library.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Really?

Victoria Jamieson:

It's like, "You're here all the time anyway, just work here." She was a stay-at-home mom when we were younger, and she was always volunteering, she organized the summer reading program at the library, so just always felt like it was part of our lives. I had kind of an ownership, I felt like, over the library. So yeah, I read all the time. My favorite books were Ramona. I loved the Ramona Quimby books. They're the ones I read over and over and over and over again.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you find, when you were in middle school, were you still in the library a lot, into books a lot in middle school? Did things shift when you moved or were you always kind of bookish throughout?

Victoria Jamieson:

No, I actually had kind of a pause in my reading life in middle school and even high school. When I moved, I was so afraid to do anything. I don't remember going to the library that often with class and middle school. It was just kind of a room there. I wish I'd had that safety and comfort of being able to go to the library. I just never did. I think school, I was very academic. I was always concerned about getting good grades. So through middle school and definitely to high school, I just read what we read in class, focused on my grades and reading for pleasure took a backseat. The things I did read for pleasure were rereading. I loved Anne of Green Gables as I got into middle school and that was something I reread a lot for comfort because I felt so awkward and uncomfortable at school. It really was nice to have that comfortable world to slip into.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I've read that you didn't read comics, you weren't into comics when you were young. Is that true?

Victoria Jamieson:

I wasn't into comic books, so I never read Spider-Man, X-Men, Superman just because it felt like that wasn't my interest. I loved books like Ramona that was talking about real kids, real families. But I did love the Sunday comics. I read Calvin and Hobbs, loved Calvin and Hobbs and the books that they put together of Calvin and Hobbs. For Better or For Worse was one of my favorites because that was about real kids, and those kids were kind of the same age as me and my brothers, so I just felt a weird parallel between those families. My mom and I kept reading that well until when I ta off to college. She would send me clip out newspaper clippings and send me the latest latest For Better or For Worse and we'd gossip about them as if they're real people.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay. So you did find yourself interested in comic strips, but comic books, at least as they were then, were not something that you gravitated towards.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I would check out like Peanuts collections or Calvin and Hobbs collections or Far Side. I love The Far Side too. For me, I really became aware of graphic novels for kids with Raina Telgemeier, and honestly, I feel like she really changed the landscape for a lot of kids' creators. There were plenty of graphic novels before that. I'm not saying Raina Telgemeier was the first graphic novelist, but I feel like Smile made such a big sensation and it was the first time I saw graphic novels being welcomed into school libraries. I was always more on the publishing side, like book side rather than comics, and that was the first time I saw such a big crossover where comics really became integrated into traditional publishing and school libraries.

Beezus opened the basement door and gently set Picky-Picky on the top step. "Nighty-night." she said tenderly. "Young lady," began Mr. Quimby. "Young lady," again. Now Beezus was really going to catch it. "You're getting all together too big for your britches lately. Just be careful how you talk around this house." Still, Beezus did not say she was sorry. She did not burst into tears. She simply stalked off to her room. Ramona was the one who burst into tears. She didn't mind when she and Beezus quarreled. She even enjoyed a good fight now and then to clear the air, but she could not bear it when anyone else in the family quarreled. And those awful things Beezus said, were they true? "Don't cry, Ramona." Mrs. Quimby put her arm around her younger daughter. "We'll get another pumpkin." "But it won't be as big," sobbed Ramona who wasn't crying about the pumpkin at all.

She was crying about important things like her father being cross so much now that he wasn't working and his lungs turning black and Beezus being so disagreeable when before she'd always been so polite to grownups and anxious to do the right thing. "Come on, let's all go to bed and things will look brighter in the morning," said Mrs. Quimby. "In a few minutes." Mr. Quimby picked up a package of cigarettes he had left on the kitchen table, shook one out, lit it, and sat down, still looking angry. Were his lungs turning black this very minute, Ramona wondered? How would anyone know when his lungs were inside him? She let her mother guide her to her room and tuck her into bed. "Now don't worry about your jack-o-lantern. We'll get another pumpkin. It won't be as big, but you'll have your jack-o-lantern." Mrs. Quimby kissed Ramona goodnight. "Nighty-night," said Ramona in a muffled voice.

As soon as her mother left, she hopped out of bed and pulled her old panda bear from under the bed and tucked it under the covers beside her for comfort. The bear must have been dusty because Ramona sneezed. "Gesundheit," said Mr. Quimby, passing by her door. "We'll carve another Jack Lantern tomorrow. Don't worry." He was not angry with Ramona. Ramona snuggled down with her dusty bear. Didn't grownups think children worried about anything but jack-o-lanterns? Didn't they know children worried about grownups?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Beverly Cleary was born in 1916 and released her first novel in 1950. The first time Ramona Quimby was introduced was in 1955. Amazingly, what Cleary tapped into nearly 70 years ago still feels relevant and fresh. Ramona's run lasted 44 years. But the impact on generations of readers and writers continues to this day. You may remember one of my earlier guests, Renee Watson, whose Ryan Hart series was inspired by Ramona. There are many reasons why Cleary's readers have felt such a deep connection with Ramona. For Vicki, it was all about the raw realness of the character. It was the way that Cleary was able to put on paper exactly how it feels to be a kid in that messy, confusing and gritty kind of way.

Victoria Jamieson:

I think the reason I loved Ramona so much was that I felt like she, I guess it was Beverly Cleary, but I feel like Ramona was saying things I felt all the time. I worried about things all the time. I remember that feeling of grownups thinking we had it easy. I remember my dad saying things like, "You kids have it made in the shade. You don't have to work. You don't have to pay taxes. You've got nothing to worry about." And I was like, "I worry all the time." I worried about robbers breaking into our house.

I worried about hurricanes coming and blowing our house down. I think these worries and fears kids have are just as real as grownups fears, and in many ways they're stronger because now when I hear a noise at night, I'm like, it's probably the wind. I'm not going to worry about it. Go back to sleep. But as a kid, I'd hear a noise and I'd be like, that's someone breaking into my house and they're going to come in and kill my entire family. I think as grownups, I have that life experience to know it's probably not someone breaking into my house, but as a kid, it just felt like anything could happen. I didn't have that experience to tell me it's probably okay.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, that's such a good point. And I definitely remember those stories of Ramona. That makes complete sense. So Beverly Cleary and Ramona have obviously had this really strong impact on your life, on your reading life. Do you feel like Ramona has an equal impact on your storytelling as a writer?

Victoria Jamieson:

Definitely. So one part of my early career, I think every book I've written has aspired to be Ramona. And my whole career I've been like, "Yeah, I was really inspired to be a writer and illustrator because of Ramona." And an early story, early in my career before I wrote Roller Girl, I had just wanted to be an illustrator. I hadn't really written that many things before. So one day, I actually got an email from Harper Collins and I'd sent them postcards with samples of my work and they said, "We're reissuing Ramona and looking for a new illustrator. Would you like to be up for the job?" I was like, "This is my dream come true." This is what I was born to do. I really felt this was my calling, my destiny. I'd finally made it. And so I took all the books out of the library.

I reread them again for the first time, I'd say, in 10 years. I carefully put together my package of samples and I sent it to the publisher. I made it through the first round of cuts, but I didn't make it through the second round of cuts. They went with somebody else and I was devastated because I really thought this was what I was meant to do. I was super broke. I was working part-time jobs, trying to become a children's author and illustrator, but that was also the same time I had started playing roller derby. So I think some of that strength for Ramona had to come out then where I was like, okay, I won't be doing Ramona, so I'll just need to do my own thing, create my own characters and try to channel Ramona that way. And so that's when I really dug into making Roller Girl. That's what really inspired me, I think, to really said about creating my own stories was that rejection.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was it that made you just say, I feel prepared, ready to also write, to actually create something in its entirety and not just a part of it? Was it that rejection that led you to that or where did that link happen?

Victoria Jamieson:

I think I started writing my own stories because it stemmed from drawing. I often tell kids that when I write a story, it always starts with drawing for me. I think other authors obviously work differently, but when I started off in my career, I started working at a publisher. I was working at Harper Collins as a book designer, and I was pretty bad at that job. A big part of my job was taking notes during meetings. I was also bad at that part of my job because that's when I started drawing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Were you doodling them?

Victoria Jamieson:

I was doodling, not even doodling to what they were talking about. It was in my own head, like doodling a pig doing gymnastics.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The best book I love. Okay, but go ahead.

Victoria Jamieson:

So that was the impetus for my first book because I kept drawing this pig like ice skating just because I thought it was funny to just amuse myself. That really was the inspiration to write a story because I'd worked in publishing enough to see how illustrators were hired. So I was like, do I wait for someone else to write a story about a pig in the Olympics and then they somehow picked me to illustrate it? That's a one in a 10 billion chance. That would never happen. I just need to write these stories so I can draw a pig doing gymnastics. That was really how I started writing and illustrating, because I had things in my head I wanted to draw, so I'd write the stories to go along with it. And then for my first graphic novel, I had only done picture books up to that point, maybe two, maybe three picture books.

I was playing roller derby and I was obsessed with it. I was like, how can I make a picture book about roller derby? And my derby friends and I were trying to come up with ideas and they were all terrible because it's a violent sport. It's not really picture book material. That was when I read Smile. Smile had just come out and I read it and I thought, okay, now I can tell a story with pictures, it can be longer, it can be a little more grown up in subject matter. Just seemed like the perfect fit.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Graphic novels, specifically of the sort that Vicki creates, are rapidly becoming a more popular and accepted medium for young readers of all ages. As we heard from Vicki, when she was a kid, this type of content simply wasn't around. She just cited Raina Telgemeier's, Smile, as the first time she even became aware of this niche, but even that came out as recently as 2010. With Roller Girl hitting shelves in 2015, Vicki became a bit of a pioneer of the format, though she's hesitant to call herself that.

Victoria Jamieson:

It's exciting to see how it's growing. I definitely don't feel like a pioneer. I always feel, like I said, I think Raina Telgemeier, Cece Bell, especially Raina, I think she really opened the doors for all the books that we see today.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Roller Girl's main character is a feisty 12 year old girl named Astrid. Astrid's story begins when she decides to go to roller derby camp and to her surprise, her best friend opts to go to ballet camp instead. The situation provides her with the opportunity to discover who she is outside of her best friend and learn important lessons about growing up and doing the right thing. Astrid is an incredibly relatable character, especially for young girls. Sometimes she gets things right, sometimes she doesn't, but she always strives to do her best. While the story and writing on their own are wonderful, the medium of a graphic novel is a major reason why this character is so effective.

Victoria Jamieson:

I think for graphic novels in general, one thing that makes me feel very connected to graphic novels is that feeling of being invited into somebody's house. Because in a graphic novel, I don't describe where they are, but I need to decide, okay, what does her house look like? What does her bedroom look like? What kind of posters are on her wall? So I always picture it like I'm just peeking in through somebody's window and getting to see where they live. And for me, that creates a really intimate reading experience because you're just in their house, you're invited into their house, into their families, into their bedroom, and that makes you feel connected right away. As for Astrid in general, I think for all of my books, they all go back to my experiences, things that happened to me when I was a kid. My feelings, I try and remember as honestly as I can, the way I felt.

A big part of Roller Girl, I don't think Astrid is very much like me, but one thing she was like me in was that she really loves her best friend. I think that's where a lot of the feeling for that book came from because when I moved to Florida, I left my best friend, Nicole, who lived in Pennsylvania. I just remember that hurt and how bad it felt. And again, where grownups sometimes don't take the issues of kids very seriously, grownups will be like, "Oh, you're going to make new friends. It'll be fine." But that was a big loss for a kid. It was the first real loss, I think, I had. And so I wanted to really dive into that and how she would feel if she had this loss and felt this betrayal and how hurt she would be and the way she would react honestly, if those things happened.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Despite the unique qualities graphic novels offer young readers, the medium has still faced a bit of a struggle for validation. Ask any book seller or librarian or me, and they will certainly have stories to share about parents who express concerns that their kids will only ever read comics. While Vicki loves and understands the value of graphic novels, she empathizes with parents who struggle with their children's reading journeys.

Victoria Jamieson:

Before I had kids, I always thought that'd be one of the great pleasures. I couldn't wait to bring them to the library like my mom did with us and do summer reading programs. But even from two years old, when I take my son to the library, he would scream when we went to story time. All he wanted do is leave that room and get out. As he got a little older, we still read a story at bedtime every night. He's eight years old. But I'd say when he was about three or four, the books he would pick out for bedtime stories were Lego manuals. There's no words. It would just be like, "Okay, step 37, put the red brick on top of the yellow brick." I'd have to just read it-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Narrate it?

Victoria Jamieson:

As if it were a story. So I'm really getting a taste of my own medicine because I meet lots of parents and some teachers, but mostly parents who tell me this sort of thing where they're like, "My kid only reads graphic novels. I want them to read other things." And I'll think like, do you know what I do? They know I make graphic novels. But I think kids, they have their own choices. They have their own desires and interests. So my son didn't want to read Ramona, but he loves looking at instructional manuals. He loves reading books about math now. So I really had to live the words I'm saying to people, which is like, "It doesn't matter what your kid is reading. I think if they cultivate a joy of reading, that's the most important thing."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In the end, we all just want what's best for our kids. But in having these blanket ideas such as novels being good, comics being bad, or concerns exclusively about age and reading level, not only are some adults creating a restrictive environment and discouraging reading, but they're also missing out on the value that these different types of reading offer. This fear from parents is understandable. Many of us were raised in a time when there was a constant line in the sand between good reading and bad reading, real literature versus junk. Nowadays, there's a huge body of research showing that these distinctions were both totally arbitrary and completely inaccurate.

Kids benefit most just from reading willingly and reading often, but it's hard for many parents to recognize and cast off the outdated biases that were drilled into us. A related concern parents sometimes have, especially with quick reads like comic books or graphic novels, is that kids develop a habit of rereading the same content over and over as opposed to moving on to new or more complex stories. Vicki mentioned earlier the emotional comforts of a good reread, but she feels the benefits go well beyond familiarity.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. I just keep reminding myself, I reread books all the time and I got something from it. At a certain point when I was in elementary school, my librarian stopped me from taking out Ramona. She's like, "You're a good reader. You've read this too many times. It's time for you to branch out and read something else."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh really?

Victoria Jamieson:

And I get that impetus, I do, but I read one other book and I was like, "Okay, now can I read Ramona again?" And so maybe it's hard for us as grownups to see what they're getting out of it. I know my librarian wanted me to branch out and see new things, but I was getting something out of rereading Ramona. My son is getting something out of rereading Batpig or a Dog Man, which is another book series I love. I think those books are a lot more complex than often grownups give them credit for. Dog Man does something I love to do in my books where you'll see something in the art, but then the character will say, "No, that's not what you're seeing. I'm not doing that. I'm not building an evil robot."

And you're like, "Oh, I can see it." So those are life skills. You see something with your own eyes, but people are telling you something else. So you're constantly making judgment calls in graphic novels. What's true? The art or the words? And making sense out of the two together. And I think that's a life skill you can learn from Dog Man and you can apply later in life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Kids definitely reread. I think it's akin to writing the first draft, just the first draft. Right? Everything happens in the revisions. It's probably similar to that in reading.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. And with graphic novels, you've got so many details in the art that the artist spends a lot of time making. So I'm always honored when kids reread it and ask about little things I've drawn that shows they're really paying attention.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Have you had somebody ask you about something that surprised you? "Oh, they noticed it. Nobody notices that."

Victoria Jamieson:

That there were two in All's Faire. One was, I drew Astrid in a little tiny scene in a crowd scene and a few kids have written and said, "Is that Astrid in the crowd in the Renaissance fair?" And then another kid, there's a teacher in All's Faire who has a mustache. In one panel, I just forgot to draw his mustache and so an eagle-eyed reader sent me an email.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I could look for that. They know. It's like the movies. It's fun when you notice something like, no, they weren't there. Yeah, there's something. Actually, I marked it. I love this scene when she sees her friend being like, "She seems fine. I'm just going to leave her." Imogene said, "I'm just going to let her be. She can defend herself alone." But then she looks a little closer and then you see she's almost crying. She's shaking a little. I thought that was kind of a meta thing because that is what the book... If you're just looking... I think graphic novels, the format, sort of makes you just look a little closer because you're not going to get it all if you just read the words on the page.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. And I think that's another reason I'm really drawn to graphic novels because as a shy kid or I see with my own son who's not really shy, but they can't always verbalize what they're thinking. I certainly didn't always express all my feelings in words. So sometimes with my son, I need to look, see how he is reacting, see what his body language is doing because maybe kids don't have the vocabulary or the... I don't know. I didn't have the confidence to say everything I was feeling, so I kept a lot inside. So I think that's something else I love about graphic novels. You can show a lot happening in the pictures and the kid is just saying, "I'm fine," but you see everything else crashing around them.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

These techniques and possibilities unique to graphic novels have allowed Vicki to merge her passion for drawing and her passion for storytelling to create relatable characters in stories and kids love them. My daughter, Florence, is one of those kids. Flo tells me that Roller Girl is one of the most popular books in her school library and to get it, you have to be put on a wait list. In 2020, Vicki brought a much deeper and emotional story to the panels to truly test their capabilities. When Stars are Scattered is a true account of Omar Mohamed's journey fleeing Somalia and living at a refugee camp in Kenya with his younger brother, Hassan. Omar, himself, was a co-author. As with Roller Girl, When Stars are Scattered hooked Florence. She had her own question for Vicki about the writing process.

Florence:

What was it like writing someone else's story since your other books are mostly about your own experiences?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, it was very different. I talked before about how I was very shy as a kid. I'm more outgoing now, but I'm still a pretty introverted person, I think a lot of authors are, where I spent a lot of time in my own own little studio making up my own stories in my head. This was the first time I worked with a co-author. I felt uncomfortable sometimes because I had to ask Omar very personal questions, hard questions about some of the hardest points in his life. I felt bad sometimes asking these questions, but I felt very lucky in having Omar as my co-author because he's a very warm person. He's very funny and very welcoming. The only reason I made this book in the first place was because he wanted to tell his story. So anytime I started to worry about that, about asking those questions or apologize for asking him to elaborate on some difficult part of his story, he'd say, "Don't worry. Thank you for asking these questions. I want my story to be out there. You're helping me tell my story."

But it did take some getting used to. I also had to learn to really remove myself as much as possible in the story. That was a learning process for me. I was used to just writing fiction so I could make things up. So in the early stages of When Stars are Scattered, if I reached a point where I didn't know what would happen next, I would try and make something up, but it would never work and it was wrong. I'd show it to Omar and he's like, "No, that's not what happened. Here's what actually happened." It was a much better for the story and I had to learn that oh, this is not my story at all. My job was not to put myself into it in any way as much as I could. My job was to listen and to write down what Omar is saying and try to remove myself as much as possible from the equation. I tried to be more of a reporter than anything else, which was new for me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Do you remember some of the things that you would have to ask him or certain scenes in the book that you realize I need more?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, and actually I never had done any reporting or interviewing really before. So I asked a friend of mine, who is a journalist, if she had any tips. One of her tips was, you often get the best answer when you ask two or three follow-up questions. So ask the question once and then ask another question about it, another one. So I remember in one meeting, he told me that his brother, Hassan, who is non-verbal, he said he only ever made noises and maybe one word. And so I asked, "What was that word?" And he said the word was Hooyo. And I said, "Well, what does Hooyo mean?" And he said, "Hooyo means mama." Even now I get goosebumps when I say that because I remember him telling me that. I think I held it together for the rest of our meeting.

But I was like, "Okay, thanks, Omar. I think that's good for today. See you in two weeks." I got in my car and I had to pull off the highway. I was just sobbing. I was crying so hard because at the time, my son was about four and he was a late talker. He had speech delays, but he always said, mama. So just that feeling of this kid who only said one word his whole life and it's mama, it's something like that I would never have been able to make up. It was so impactful to me. Now actually, Hassan is a grownup and he actually says a second word, which is aye, which also means mama. So now he says two words, but they both mean mama.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh my God, I'm crying.

Victoria Jamieson:

I can see you're crying.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay. Was there difficulty in having him go back and revisit memories that he probably didn't want to?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, and that was something we had to discuss in writing the book because no one becomes a refugee because your life is easy. Lots of difficult things happened to Omar. One of the scenes we struggled with how to portray in the book was Omar saw his father killed in front of him. That's why he ran. But how do you show that in a book for children meant for young writers, for young readers and be honest, but not be graphic or overwhelming? So there were lots of details like that that we had to really navigate carefully because we wanted to be honest because the truth was, he was a kid. Most refugees in the world are children, so children all over the world live these realities, but not to present it in a way that's overwhelming or terrifying to children in the US who have the luxury, the privilege of not facing those things in lives, hopefully.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I think, like you said, graphic novels give you this intimacy because you really are seeing something as you're reading it and you get this, I liked how you described it, you're peering into the window. In this case, you're like peering into the window of someone's life and story. This type of story would be something that maybe would be very difficult for kids, of certain ages, certainly to read to otherwise consume. But I think that when stars are scattered makes it possible to really share an experience with younger kids.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I hear that from teachers a lot, that graphic novels is kind of a way to introduce hard complex subjects to younger readers, but honestly, I don't think about how it's going to be received while I'm writing it. I never really thought, oh, I'll write it as a graphic novel because more kids will read it that way. I thought a graphic novel was good for Omar's story, for myself, just because I was unfamiliar with what a lot of things look like. Our imagination is limited by our experiences. So one example is when Omar told me he and his brother lived in a tent for 15 years, I picture a tent you buy at a camping store or you see in cartoons. I'd never seen tents that people made themselves or how they used sticks to bind them together and then they used tarps from the United Nations to put on top.

Or school, I didn't know what school in a refugee camp looked like. So as a graphic novel, I could show what life looked like, what homes looked like, bathrooms, what the camp looked like. That's something I had no experience with, so I didn't know what it looked like until I looked up photographs of it. So I think it's a bonus that kids love graphic novels, that it's more accessible for them. But for me, it just felt like the best way to tell Omar's story and it's the way I love telling stories. I think there's so much you can do. It's so rich because you have words, you have pictures. Sometimes they say the same things, sometimes they say opposite things. There's such an interplay between the two that I feel like there's so many possibilities.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yes, so many possibilities. Let's talk now about the connection that you are forming with your kids through your writing. I guess I'd imagine that kids would feel like they know you in a deeper sense because not only are you writing the stories, but they get to see your artwork, not to mention how much of yourself that you're actually putting into your work. So I know you do a lot of school visits and I was wondering if there's anything that stands out to you or anyone that stands out to you is particularly memorable?

Victoria Jamieson:

One that comes to mind, just because it was a few weeks ago, was, I know in your podcast you've talked a lot about book bans and all the challenges librarians are facing and it's just made librarian's jobs so difficult. I went to a school recently in a town that's made national news for book banning, and the librarian had contacted me a few weeks before my visit and she's like, "I'm getting some objections. Do you have list of your awards, so I could say, 'No, we really should have this author here. She's not problematic.'" So I was really nervous about that day because it's a very conservative town. There was some people who objected to my coming and I was like, "This is going to be awful. It's going to be a terrible day."

But then I went to the school and everybody was so warm and so welcoming. The students were so excited, the administration was welcoming, the librarian. I just felt so welcome and so warm all day. So that was a reminder to me that there can be a few voices that are very loud, but they don't speak for everybody. There are a few dissenting voices in the community, but overall my welcome was amazing. I try to keep that in mind with all the challenges facing librarians. I just have a lot of empathy for librarians who are on the frontline facing all of those challenges because it's not easy.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You mean they're objecting to you, your own personal statements to your books, to your work? What is objection?

Victoria Jamieson:

I think these particular objections were Roller Girl uses the word ass, so they had problems with that. And then in All's Faire in Middle School, the word sex is mentioned. I've had very few objections or I have not faced at all the kind of banning that other authors have, but when I received those few emails, it's like, "Well, why did you include the word ass? This is a book for children. Children shouldn't be facing that kind of language." I always try and respond with, "I want to be honest in my books. If you've been near a middle school, you'll hear language that will make your ears bleed." That's just something kids do as they get older. It's trying out new things. And for me, again, in middle school, that was something that shocked and scared the living daylights out of me, all these kids using terrible language. What's happening?

I don't belong here. But kids are going to face it. If you face it first in a book, if your friend, Astrid, I hope my characters all become friends to my readers, if your friend gets called a bad name and you see how they can react to it, how they can turn it around and not let it define them, I hope that will give kids the confidence to face those own things when they face them, because they're going to face them. It's not an if, if it's a when. So I think books that are honest can help prepare kids for when those things happen to them.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When you go to the school, you said you felt welcome. Do they make you lots of signs? Do you get to meet with everybody all at once? Just certain classes? At the one you went to recently.

Victoria Jamieson:

They do you make signs. It's always nice. Students are often the ones making the artwork, so I love that. Usually, schools have limited funding, so usually I visit, do big assemblies for most of the grades. But one of my favorite parts is always if I can have lunch with students. Sometimes librarians will have contests or make a comic or write an essay about why you want to meet the author. So then it's a group of 15 or 20 kids. That's one of my favorite parts because we can talk about books, talk about writing, and I get to talk to the kids one-on-one.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, they must make you some great comics. I can only imagine.

Victoria Jamieson:

They do. They do. I've got a stack of drawings. I keep them all because I love them, and if I'm having a bad writing day, I can look at a kid's letter and it will cheer me up immediately.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

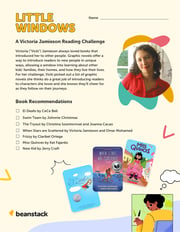

For Vicki's reading challenge, Little Windows, she invites us to embrace graphic novels, to look through some new little windows and discover new characters to fall in love with.

Victoria Jamieson:

So I have always loved books that introduced me to other people. I just am so curious about how other people live. As a kid, I loved hearing about other kids' families and their home lives and how they live their lives. So I picked out a list of graphic novels that I think do a great job of introducing you to different characters, characters you'll love, characters you'll cheer for and follow on their journeys. Yeah, so just a selection of graphic novels that I love. One of my favorites of all time is El Deafo by Cece Bell, which I'm sure a lot of your listeners have read already, but it's one of my favorites. I included on every list along with newer books like Swim Team by Johnnie Christmas and The Tryout by Christina Soontornvat was my favorite recent graphic novels. There's so many great ones to choose from these days. It's a wealth of great graphic novels.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You can check out Vicki's challenge and all of our author reading challenges at the readingculturepod.com. And before we sign off, let's hear from another amazing educator working to build a strong culture of reading at their school. Today's featured librarian is John Henry Evans, a school librarian at Walter T. Helms Middle School at West Contra Costa Unified District in California. John Henry shared a moving story about a student, a book, and an unexpected post-it note.

John Henry Evans:

So when I think about what a strong library can do for students and how important it is to protect freedom of reading, I really think about this thing that happened to me last year when a student came in and checked out the novel Gender Queer, which if you haven't read the novel, it's about a person who's transitioning. When they returned it, as I was checking it in, a lot of times people will leave things behind. So I go to pull it out and I realize this student has left a Post-it on the front page that said, "This is my name, and if you check out this book, come and find me and tell me about what encouraged you to read it, because I want to talk to you." I think it just really struck me that this book had done something so powerful for a student that they wanted it to continue. That's why I do this work because I want that to happen for as many students as possible.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture. You've been listening to our conversation with Victoria Jamieson. Again, I'm your host Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading The House of Eve by Sadeqa Johnson and Moon Flower by Kacen Callender. If you've enjoyed today's show, please show some love and rate, subscribe and share The Reading Culture among your friends and networks. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beansstack.com and join us on social media at The Reading Culture Pod for some awesome giveaways. Be sure to check out the Children's Book podcast with teacher and librarian Matthew Winner. It's a podcast made for kids ages six to 12 that explores big ideas and the way that stories can help us feel seen, understood, and valued. You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josia Lamberto-Egan. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode. Thanks for joining and keep reading. All right, that should do

My son didn't want to read Ramona, but he loves instructional manuals. He loves reading books about math now. So I really had to live the words I'm saying to people, which is like, it doesn't matter what your kid is reading. I think if they cultivate a joy of reading, that's the most important thing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Graphic novels are often a point of contention among adults and kids' lives. Should we encourage them to read comics? Should we be concerned if they prefer graphic novels to traditional prose? To put it bluntly, pretty much any type of discouragement of reading is bad, but Victoria Jamieson takes the argument further than that. As a graphic novelist herself, she understands the unique value that this type of literature offers kids.

Victoria Jamieson:

One thing that makes me feel very connected to graphic novels is that feeling of being invited into somebody's house because in a graphic novel, I don't describe where they are, but I need to decide, okay, what does her house look like? What does her bedroom look like? What kind of posters are on her wall? So I always picture it like I'm just like peeking in through somebody's window and getting to see where they live.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Vicki is the creator of the beloved Newbery Honor book Roller Girl, the harrowing real life story told a National Book Award finalist, When Stars are Scattered and various other graphic novels and picture books. In this episode, she unpacks the underrecognized value of graphic novels in children's literature, the dream job rejection that inspired her to create Roller Girl and the delicate act of honestly presenting trauma in a story for kids. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. What were you like as a kid? Younger, first? Younger, then we can get to middle school, but elementary school age?

Victoria Jamieson:

Elementary school, I was very shy, very quiet. I think people just thought I didn't talk, especially in... In school, I had my best friend, so I always talked to my best friend. I felt like I was good with one friend. But when I went to family functions or was in larger groups, I was just very quiet.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Were you one of many siblings or just you?

Victoria Jamieson:

I have an older brother and a younger brother, so I'm the middle child, but I was the only girl, so I never felt like I had middle child syndrome. I always had plenty of attention, but I'd just always like to go off of my own imagination, I think. I had lots of stuffed toys that I played with and I was pretty content on my own to not be bothered by my brothers. I could just entertain myself for a good long time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And then so in middle school was sort of same thing, you were more to yourself or always had one or two good friends?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I think everything got exacerbated in middle school like it does for most kids. My family moved from Pennsylvania to Florida when I was in seventh grade. So I'd stayed in the same town up until then, so I knew everybody. We knew all our neighbors. I had my comfort, but we moved to a new state and everything totally changed. Everything I thought I knew about being cool or making friends just didn't work. And then I definitely... That's really when the shyness kicked in. I was just so embarrassed, so self-conscious, so afraid to talk to anybody. But as a kid, I read a ton. My mom took us to the library all the time. It was kind of our second home. She wasn't a certified librarian, but after a while, we went there for so long, she just started working at the library.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Really?

Victoria Jamieson:

It's like, "You're here all the time anyway, just work here." She was a stay-at-home mom when we were younger, and she was always volunteering, she organized the summer reading program at the library, so just always felt like it was part of our lives. I had kind of an ownership, I felt like, over the library. So yeah, I read all the time. My favorite books were Ramona. I loved the Ramona Quimby books. They're the ones I read over and over and over and over again.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you find, when you were in middle school, were you still in the library a lot, into books a lot in middle school? Did things shift when you moved or were you always kind of bookish throughout?

Victoria Jamieson:

No, I actually had kind of a pause in my reading life in middle school and even high school. When I moved, I was so afraid to do anything. I don't remember going to the library that often with class and middle school. It was just kind of a room there. I wish I'd had that safety and comfort of being able to go to the library. I just never did. I think school, I was very academic. I was always concerned about getting good grades. So through middle school and definitely to high school, I just read what we read in class, focused on my grades and reading for pleasure took a backseat. The things I did read for pleasure were rereading. I loved Anne of Green Gables as I got into middle school and that was something I reread a lot for comfort because I felt so awkward and uncomfortable at school. It really was nice to have that comfortable world to slip into.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I've read that you didn't read comics, you weren't into comics when you were young. Is that true?

Victoria Jamieson:

I wasn't into comic books, so I never read Spider-Man, X-Men, Superman just because it felt like that wasn't my interest. I loved books like Ramona that was talking about real kids, real families. But I did love the Sunday comics. I read Calvin and Hobbs, loved Calvin and Hobbs and the books that they put together of Calvin and Hobbs. For Better or For Worse was one of my favorites because that was about real kids, and those kids were kind of the same age as me and my brothers, so I just felt a weird parallel between those families. My mom and I kept reading that well until when I ta off to college. She would send me clip out newspaper clippings and send me the latest latest For Better or For Worse and we'd gossip about them as if they're real people.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay. So you did find yourself interested in comic strips, but comic books, at least as they were then, were not something that you gravitated towards.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I would check out like Peanuts collections or Calvin and Hobbs collections or Far Side. I love The Far Side too. For me, I really became aware of graphic novels for kids with Raina Telgemeier, and honestly, I feel like she really changed the landscape for a lot of kids' creators. There were plenty of graphic novels before that. I'm not saying Raina Telgemeier was the first graphic novelist, but I feel like Smile made such a big sensation and it was the first time I saw graphic novels being welcomed into school libraries. I was always more on the publishing side, like book side rather than comics, and that was the first time I saw such a big crossover where comics really became integrated into traditional publishing and school libraries.

Beezus opened the basement door and gently set Picky-Picky on the top step. "Nighty-night." she said tenderly. "Young lady," began Mr. Quimby. "Young lady," again. Now Beezus was really going to catch it. "You're getting all together too big for your britches lately. Just be careful how you talk around this house." Still, Beezus did not say she was sorry. She did not burst into tears. She simply stalked off to her room. Ramona was the one who burst into tears. She didn't mind when she and Beezus quarreled. She even enjoyed a good fight now and then to clear the air, but she could not bear it when anyone else in the family quarreled. And those awful things Beezus said, were they true? "Don't cry, Ramona." Mrs. Quimby put her arm around her younger daughter. "We'll get another pumpkin." "But it won't be as big," sobbed Ramona who wasn't crying about the pumpkin at all.

She was crying about important things like her father being cross so much now that he wasn't working and his lungs turning black and Beezus being so disagreeable when before she'd always been so polite to grownups and anxious to do the right thing. "Come on, let's all go to bed and things will look brighter in the morning," said Mrs. Quimby. "In a few minutes." Mr. Quimby picked up a package of cigarettes he had left on the kitchen table, shook one out, lit it, and sat down, still looking angry. Were his lungs turning black this very minute, Ramona wondered? How would anyone know when his lungs were inside him? She let her mother guide her to her room and tuck her into bed. "Now don't worry about your jack-o-lantern. We'll get another pumpkin. It won't be as big, but you'll have your jack-o-lantern." Mrs. Quimby kissed Ramona goodnight. "Nighty-night," said Ramona in a muffled voice.

As soon as her mother left, she hopped out of bed and pulled her old panda bear from under the bed and tucked it under the covers beside her for comfort. The bear must have been dusty because Ramona sneezed. "Gesundheit," said Mr. Quimby, passing by her door. "We'll carve another Jack Lantern tomorrow. Don't worry." He was not angry with Ramona. Ramona snuggled down with her dusty bear. Didn't grownups think children worried about anything but jack-o-lanterns? Didn't they know children worried about grownups?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Beverly Cleary was born in 1916 and released her first novel in 1950. The first time Ramona Quimby was introduced was in 1955. Amazingly, what Cleary tapped into nearly 70 years ago still feels relevant and fresh. Ramona's run lasted 44 years. But the impact on generations of readers and writers continues to this day. You may remember one of my earlier guests, Renee Watson, whose Ryan Hart series was inspired by Ramona. There are many reasons why Cleary's readers have felt such a deep connection with Ramona. For Vicki, it was all about the raw realness of the character. It was the way that Cleary was able to put on paper exactly how it feels to be a kid in that messy, confusing and gritty kind of way.

Victoria Jamieson:

I think the reason I loved Ramona so much was that I felt like she, I guess it was Beverly Cleary, but I feel like Ramona was saying things I felt all the time. I worried about things all the time. I remember that feeling of grownups thinking we had it easy. I remember my dad saying things like, "You kids have it made in the shade. You don't have to work. You don't have to pay taxes. You've got nothing to worry about." And I was like, "I worry all the time." I worried about robbers breaking into our house.

I worried about hurricanes coming and blowing our house down. I think these worries and fears kids have are just as real as grownups fears, and in many ways they're stronger because now when I hear a noise at night, I'm like, it's probably the wind. I'm not going to worry about it. Go back to sleep. But as a kid, I'd hear a noise and I'd be like, that's someone breaking into my house and they're going to come in and kill my entire family. I think as grownups, I have that life experience to know it's probably not someone breaking into my house, but as a kid, it just felt like anything could happen. I didn't have that experience to tell me it's probably okay.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, that's such a good point. And I definitely remember those stories of Ramona. That makes complete sense. So Beverly Cleary and Ramona have obviously had this really strong impact on your life, on your reading life. Do you feel like Ramona has an equal impact on your storytelling as a writer?

Victoria Jamieson:

Definitely. So one part of my early career, I think every book I've written has aspired to be Ramona. And my whole career I've been like, "Yeah, I was really inspired to be a writer and illustrator because of Ramona." And an early story, early in my career before I wrote Roller Girl, I had just wanted to be an illustrator. I hadn't really written that many things before. So one day, I actually got an email from Harper Collins and I'd sent them postcards with samples of my work and they said, "We're reissuing Ramona and looking for a new illustrator. Would you like to be up for the job?" I was like, "This is my dream come true." This is what I was born to do. I really felt this was my calling, my destiny. I'd finally made it. And so I took all the books out of the library.

I reread them again for the first time, I'd say, in 10 years. I carefully put together my package of samples and I sent it to the publisher. I made it through the first round of cuts, but I didn't make it through the second round of cuts. They went with somebody else and I was devastated because I really thought this was what I was meant to do. I was super broke. I was working part-time jobs, trying to become a children's author and illustrator, but that was also the same time I had started playing roller derby. So I think some of that strength for Ramona had to come out then where I was like, okay, I won't be doing Ramona, so I'll just need to do my own thing, create my own characters and try to channel Ramona that way. And so that's when I really dug into making Roller Girl. That's what really inspired me, I think, to really said about creating my own stories was that rejection.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was it that made you just say, I feel prepared, ready to also write, to actually create something in its entirety and not just a part of it? Was it that rejection that led you to that or where did that link happen?

Victoria Jamieson:

I think I started writing my own stories because it stemmed from drawing. I often tell kids that when I write a story, it always starts with drawing for me. I think other authors obviously work differently, but when I started off in my career, I started working at a publisher. I was working at Harper Collins as a book designer, and I was pretty bad at that job. A big part of my job was taking notes during meetings. I was also bad at that part of my job because that's when I started drawing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Were you doodling them?

Victoria Jamieson:

I was doodling, not even doodling to what they were talking about. It was in my own head, like doodling a pig doing gymnastics.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The best book I love. Okay, but go ahead.

Victoria Jamieson:

So that was the impetus for my first book because I kept drawing this pig like ice skating just because I thought it was funny to just amuse myself. That really was the inspiration to write a story because I'd worked in publishing enough to see how illustrators were hired. So I was like, do I wait for someone else to write a story about a pig in the Olympics and then they somehow picked me to illustrate it? That's a one in a 10 billion chance. That would never happen. I just need to write these stories so I can draw a pig doing gymnastics. That was really how I started writing and illustrating, because I had things in my head I wanted to draw, so I'd write the stories to go along with it. And then for my first graphic novel, I had only done picture books up to that point, maybe two, maybe three picture books.

I was playing roller derby and I was obsessed with it. I was like, how can I make a picture book about roller derby? And my derby friends and I were trying to come up with ideas and they were all terrible because it's a violent sport. It's not really picture book material. That was when I read Smile. Smile had just come out and I read it and I thought, okay, now I can tell a story with pictures, it can be longer, it can be a little more grown up in subject matter. Just seemed like the perfect fit.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Graphic novels, specifically of the sort that Vicki creates, are rapidly becoming a more popular and accepted medium for young readers of all ages. As we heard from Vicki, when she was a kid, this type of content simply wasn't around. She just cited Raina Telgemeier's, Smile, as the first time she even became aware of this niche, but even that came out as recently as 2010. With Roller Girl hitting shelves in 2015, Vicki became a bit of a pioneer of the format, though she's hesitant to call herself that.

Victoria Jamieson:

It's exciting to see how it's growing. I definitely don't feel like a pioneer. I always feel, like I said, I think Raina Telgemeier, Cece Bell, especially Raina, I think she really opened the doors for all the books that we see today.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Roller Girl's main character is a feisty 12 year old girl named Astrid. Astrid's story begins when she decides to go to roller derby camp and to her surprise, her best friend opts to go to ballet camp instead. The situation provides her with the opportunity to discover who she is outside of her best friend and learn important lessons about growing up and doing the right thing. Astrid is an incredibly relatable character, especially for young girls. Sometimes she gets things right, sometimes she doesn't, but she always strives to do her best. While the story and writing on their own are wonderful, the medium of a graphic novel is a major reason why this character is so effective.

Victoria Jamieson:

I think for graphic novels in general, one thing that makes me feel very connected to graphic novels is that feeling of being invited into somebody's house. Because in a graphic novel, I don't describe where they are, but I need to decide, okay, what does her house look like? What does her bedroom look like? What kind of posters are on her wall? So I always picture it like I'm just peeking in through somebody's window and getting to see where they live. And for me, that creates a really intimate reading experience because you're just in their house, you're invited into their house, into their families, into their bedroom, and that makes you feel connected right away. As for Astrid in general, I think for all of my books, they all go back to my experiences, things that happened to me when I was a kid. My feelings, I try and remember as honestly as I can, the way I felt.

A big part of Roller Girl, I don't think Astrid is very much like me, but one thing she was like me in was that she really loves her best friend. I think that's where a lot of the feeling for that book came from because when I moved to Florida, I left my best friend, Nicole, who lived in Pennsylvania. I just remember that hurt and how bad it felt. And again, where grownups sometimes don't take the issues of kids very seriously, grownups will be like, "Oh, you're going to make new friends. It'll be fine." But that was a big loss for a kid. It was the first real loss, I think, I had. And so I wanted to really dive into that and how she would feel if she had this loss and felt this betrayal and how hurt she would be and the way she would react honestly, if those things happened.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Despite the unique qualities graphic novels offer young readers, the medium has still faced a bit of a struggle for validation. Ask any book seller or librarian or me, and they will certainly have stories to share about parents who express concerns that their kids will only ever read comics. While Vicki loves and understands the value of graphic novels, she empathizes with parents who struggle with their children's reading journeys.

Victoria Jamieson:

Before I had kids, I always thought that'd be one of the great pleasures. I couldn't wait to bring them to the library like my mom did with us and do summer reading programs. But even from two years old, when I take my son to the library, he would scream when we went to story time. All he wanted do is leave that room and get out. As he got a little older, we still read a story at bedtime every night. He's eight years old. But I'd say when he was about three or four, the books he would pick out for bedtime stories were Lego manuals. There's no words. It would just be like, "Okay, step 37, put the red brick on top of the yellow brick." I'd have to just read it-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Narrate it?

Victoria Jamieson:

As if it were a story. So I'm really getting a taste of my own medicine because I meet lots of parents and some teachers, but mostly parents who tell me this sort of thing where they're like, "My kid only reads graphic novels. I want them to read other things." And I'll think like, do you know what I do? They know I make graphic novels. But I think kids, they have their own choices. They have their own desires and interests. So my son didn't want to read Ramona, but he loves looking at instructional manuals. He loves reading books about math now. So I really had to live the words I'm saying to people, which is like, "It doesn't matter what your kid is reading. I think if they cultivate a joy of reading, that's the most important thing."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In the end, we all just want what's best for our kids. But in having these blanket ideas such as novels being good, comics being bad, or concerns exclusively about age and reading level, not only are some adults creating a restrictive environment and discouraging reading, but they're also missing out on the value that these different types of reading offer. This fear from parents is understandable. Many of us were raised in a time when there was a constant line in the sand between good reading and bad reading, real literature versus junk. Nowadays, there's a huge body of research showing that these distinctions were both totally arbitrary and completely inaccurate.

Kids benefit most just from reading willingly and reading often, but it's hard for many parents to recognize and cast off the outdated biases that were drilled into us. A related concern parents sometimes have, especially with quick reads like comic books or graphic novels, is that kids develop a habit of rereading the same content over and over as opposed to moving on to new or more complex stories. Vicki mentioned earlier the emotional comforts of a good reread, but she feels the benefits go well beyond familiarity.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. I just keep reminding myself, I reread books all the time and I got something from it. At a certain point when I was in elementary school, my librarian stopped me from taking out Ramona. She's like, "You're a good reader. You've read this too many times. It's time for you to branch out and read something else."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh really?

Victoria Jamieson:

And I get that impetus, I do, but I read one other book and I was like, "Okay, now can I read Ramona again?" And so maybe it's hard for us as grownups to see what they're getting out of it. I know my librarian wanted me to branch out and see new things, but I was getting something out of rereading Ramona. My son is getting something out of rereading Batpig or a Dog Man, which is another book series I love. I think those books are a lot more complex than often grownups give them credit for. Dog Man does something I love to do in my books where you'll see something in the art, but then the character will say, "No, that's not what you're seeing. I'm not doing that. I'm not building an evil robot."

And you're like, "Oh, I can see it." So those are life skills. You see something with your own eyes, but people are telling you something else. So you're constantly making judgment calls in graphic novels. What's true? The art or the words? And making sense out of the two together. And I think that's a life skill you can learn from Dog Man and you can apply later in life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Kids definitely reread. I think it's akin to writing the first draft, just the first draft. Right? Everything happens in the revisions. It's probably similar to that in reading.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. And with graphic novels, you've got so many details in the art that the artist spends a lot of time making. So I'm always honored when kids reread it and ask about little things I've drawn that shows they're really paying attention.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Have you had somebody ask you about something that surprised you? "Oh, they noticed it. Nobody notices that."

Victoria Jamieson:

That there were two in All's Faire. One was, I drew Astrid in a little tiny scene in a crowd scene and a few kids have written and said, "Is that Astrid in the crowd in the Renaissance fair?" And then another kid, there's a teacher in All's Faire who has a mustache. In one panel, I just forgot to draw his mustache and so an eagle-eyed reader sent me an email.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I could look for that. They know. It's like the movies. It's fun when you notice something like, no, they weren't there. Yeah, there's something. Actually, I marked it. I love this scene when she sees her friend being like, "She seems fine. I'm just going to leave her." Imogene said, "I'm just going to let her be. She can defend herself alone." But then she looks a little closer and then you see she's almost crying. She's shaking a little. I thought that was kind of a meta thing because that is what the book... If you're just looking... I think graphic novels, the format, sort of makes you just look a little closer because you're not going to get it all if you just read the words on the page.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah. And I think that's another reason I'm really drawn to graphic novels because as a shy kid or I see with my own son who's not really shy, but they can't always verbalize what they're thinking. I certainly didn't always express all my feelings in words. So sometimes with my son, I need to look, see how he is reacting, see what his body language is doing because maybe kids don't have the vocabulary or the... I don't know. I didn't have the confidence to say everything I was feeling, so I kept a lot inside. So I think that's something else I love about graphic novels. You can show a lot happening in the pictures and the kid is just saying, "I'm fine," but you see everything else crashing around them.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

These techniques and possibilities unique to graphic novels have allowed Vicki to merge her passion for drawing and her passion for storytelling to create relatable characters in stories and kids love them. My daughter, Florence, is one of those kids. Flo tells me that Roller Girl is one of the most popular books in her school library and to get it, you have to be put on a wait list. In 2020, Vicki brought a much deeper and emotional story to the panels to truly test their capabilities. When Stars are Scattered is a true account of Omar Mohamed's journey fleeing Somalia and living at a refugee camp in Kenya with his younger brother, Hassan. Omar, himself, was a co-author. As with Roller Girl, When Stars are Scattered hooked Florence. She had her own question for Vicki about the writing process.

Florence:

What was it like writing someone else's story since your other books are mostly about your own experiences?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, it was very different. I talked before about how I was very shy as a kid. I'm more outgoing now, but I'm still a pretty introverted person, I think a lot of authors are, where I spent a lot of time in my own own little studio making up my own stories in my head. This was the first time I worked with a co-author. I felt uncomfortable sometimes because I had to ask Omar very personal questions, hard questions about some of the hardest points in his life. I felt bad sometimes asking these questions, but I felt very lucky in having Omar as my co-author because he's a very warm person. He's very funny and very welcoming. The only reason I made this book in the first place was because he wanted to tell his story. So anytime I started to worry about that, about asking those questions or apologize for asking him to elaborate on some difficult part of his story, he'd say, "Don't worry. Thank you for asking these questions. I want my story to be out there. You're helping me tell my story."

But it did take some getting used to. I also had to learn to really remove myself as much as possible in the story. That was a learning process for me. I was used to just writing fiction so I could make things up. So in the early stages of When Stars are Scattered, if I reached a point where I didn't know what would happen next, I would try and make something up, but it would never work and it was wrong. I'd show it to Omar and he's like, "No, that's not what happened. Here's what actually happened." It was a much better for the story and I had to learn that oh, this is not my story at all. My job was not to put myself into it in any way as much as I could. My job was to listen and to write down what Omar is saying and try to remove myself as much as possible from the equation. I tried to be more of a reporter than anything else, which was new for me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Do you remember some of the things that you would have to ask him or certain scenes in the book that you realize I need more?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, and actually I never had done any reporting or interviewing really before. So I asked a friend of mine, who is a journalist, if she had any tips. One of her tips was, you often get the best answer when you ask two or three follow-up questions. So ask the question once and then ask another question about it, another one. So I remember in one meeting, he told me that his brother, Hassan, who is non-verbal, he said he only ever made noises and maybe one word. And so I asked, "What was that word?" And he said the word was Hooyo. And I said, "Well, what does Hooyo mean?" And he said, "Hooyo means mama." Even now I get goosebumps when I say that because I remember him telling me that. I think I held it together for the rest of our meeting.

But I was like, "Okay, thanks, Omar. I think that's good for today. See you in two weeks." I got in my car and I had to pull off the highway. I was just sobbing. I was crying so hard because at the time, my son was about four and he was a late talker. He had speech delays, but he always said, mama. So just that feeling of this kid who only said one word his whole life and it's mama, it's something like that I would never have been able to make up. It was so impactful to me. Now actually, Hassan is a grownup and he actually says a second word, which is aye, which also means mama. So now he says two words, but they both mean mama.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh my God, I'm crying.

Victoria Jamieson:

I can see you're crying.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay. Was there difficulty in having him go back and revisit memories that he probably didn't want to?

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, and that was something we had to discuss in writing the book because no one becomes a refugee because your life is easy. Lots of difficult things happened to Omar. One of the scenes we struggled with how to portray in the book was Omar saw his father killed in front of him. That's why he ran. But how do you show that in a book for children meant for young writers, for young readers and be honest, but not be graphic or overwhelming? So there were lots of details like that that we had to really navigate carefully because we wanted to be honest because the truth was, he was a kid. Most refugees in the world are children, so children all over the world live these realities, but not to present it in a way that's overwhelming or terrifying to children in the US who have the luxury, the privilege of not facing those things in lives, hopefully.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I think, like you said, graphic novels give you this intimacy because you really are seeing something as you're reading it and you get this, I liked how you described it, you're peering into the window. In this case, you're like peering into the window of someone's life and story. This type of story would be something that maybe would be very difficult for kids, of certain ages, certainly to read to otherwise consume. But I think that when stars are scattered makes it possible to really share an experience with younger kids.

Victoria Jamieson:

Yeah, I hear that from teachers a lot, that graphic novels is kind of a way to introduce hard complex subjects to younger readers, but honestly, I don't think about how it's going to be received while I'm writing it. I never really thought, oh, I'll write it as a graphic novel because more kids will read it that way. I thought a graphic novel was good for Omar's story, for myself, just because I was unfamiliar with what a lot of things look like. Our imagination is limited by our experiences. So one example is when Omar told me he and his brother lived in a tent for 15 years, I picture a tent you buy at a camping store or you see in cartoons. I'd never seen tents that people made themselves or how they used sticks to bind them together and then they used tarps from the United Nations to put on top.

Or school, I didn't know what school in a refugee camp looked like. So as a graphic novel, I could show what life looked like, what homes looked like, bathrooms, what the camp looked like. That's something I had no experience with, so I didn't know what it looked like until I looked up photographs of it. So I think it's a bonus that kids love graphic novels, that it's more accessible for them. But for me, it just felt like the best way to tell Omar's story and it's the way I love telling stories. I think there's so much you can do. It's so rich because you have words, you have pictures. Sometimes they say the same things, sometimes they say opposite things. There's such an interplay between the two that I feel like there's so many possibilities.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yes, so many possibilities. Let's talk now about the connection that you are forming with your kids through your writing. I guess I'd imagine that kids would feel like they know you in a deeper sense because not only are you writing the stories, but they get to see your artwork, not to mention how much of yourself that you're actually putting into your work. So I know you do a lot of school visits and I was wondering if there's anything that stands out to you or anyone that stands out to you is particularly memorable?

Victoria Jamieson: