About this episode

If Nina LaCour were a drink, she would be a cozy cup of tea. You’re not rushing to finish a conversation with Nina. Rather, you are spending time exploring the details. And that is exactly what we did in this episode.

"I spend a lot of time trying to hope that I'll remember little things and how a certain simple thing felt. … Writing is one way of trying to capture that feeling, even if I'm fictionalizing it still.” - Nina LaCour

The world moves fast. Usually faster than we’d like it to. But writing can gift us the ability to slow a moment down, to digest and analyze at a more intentional pace. For Nina LaCour, writing starts with observing the world around you, getting ready to break it down into words and unravel the meaning on a page.

As a new writer, Nina found it best to share those observations through young adult literature after falling in love with it in college. She has since written a picture book, “Mama, Mommy and Me in the Middle,” and returned to an adult novel she shelved early in her career (“Yerba Buena”). She recently released "The Apartment House on Poppy Hill," the sweetest chapter book.

Nina’s work is notably thoughtful and gentle. Her complex topics have resonated deeply with young readers and adults alike (including our own recent guest, Mark Oshiro). She’s best known for her novels such as “Hold Still,” "Everything Leads to You," and "We Are Okay," which received the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature.

In this episode, she shares her journey to falling in love with young adult literature and how Virginia Woolf helped her find the love of her life. She also explores writing's capacity to uncover the depth within every moment and discusses the importance of queer family representation in literature.

As a new writer, Nina found it best to share those observations through young adult literature after falling in love with it in college. She has since written a picture book, “Mama, Mommy and Me in the Middle,” and returned to an adult novel she shelved early in her career (“Yerba Buena”). She recently released "The Apartment House on Poppy Hill," the sweetest chapter book.

Nina’s work is notably thoughtful and gentle. Her complex topics have resonated deeply with young readers and adults alike (including our own recent guest, Mark Oshiro). She’s best known for her novels such as “Hold Still,” "Everything Leads to You," and "We Are Okay," which received the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature.

In this episode, she shares her journey to falling in love with young adult literature and how Virginia Woolf helped her find the love of her life. She also explores writing's capacity to uncover the depth within every moment and discusses the importance of queer family representation in literature.

***

Connect with Jordan and The Reading Culture @thereadingculturepod and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

***

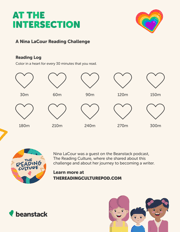

In her reading challenge, At the Intersection, Nina has curated a list of books at the intersection of queerness and family.

You can find her list and all past reading challenges at thereadingculturepod.com/nina-lacour

This episode's Beanstack Featured Librarian is Faith Rice Mills, librarian at Nelda Sullivan Middle School in Pasadena, Texas. She tells us a heartwarming story to remind librarians of the importance of their work, even when that impact isn't obvious.

Contents

-

Chapter 1 - The Outsider…

-

Chapter 2 - …Becomes the Observer

-

Chapter 3 - Mrs. Dalloway

-

Chapter 4 - On Being Gentle

-

Chapter 5 - Bang Bang

-

Chapter 6 - At the Intersection

-

Chapter 7 - Beanstack Featured Librarian

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

View Transcript

Hide Transcript

Nina LaCour:

How do you create a quiet moment on a page is such a hard lesson to learn, I think, because you have to fill it with words but you also want it to have this feeling.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour never rushes through a moment. Instead, she encourages her readers to linger in the space to contemplate and to fully experience each second. She invites us to be deep observers of the world, which is exactly what she believes makes a great writer.

Nina LaCour:

I did a few little free events for kid writers through the San Francisco Library, and I would take them on a little walk and tell them, "We're going to look and we're going to see what you want to put in your stories and we're going to listen and we're going to eavesdrop and we're going to spy on people." And that is how you become a writer, by paying attention to the world.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour's gentle and thoughtful approach to deep and complex topics have resonated with young readers and adults alike. She's known for her novels such as Hold Still, Everything Leads to You, and We Are Okay, which received the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. In this episode, she'll tell us how and why she fell in love with YA, about her admiration for writing's ability to bring out the depth in every second, and she reveals which classic 20th century novel not only influenced her writing style, but also led to her very own meet cute with a storybook ending. And of course, she tells us the origin story of her signature bangs.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators about ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways, @thereadingculturepod, and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter. All right, onto the show.

Okay. So Nina, you grew up in the Bay Area but not quite San Francisco, right? It's close by. Can you just describe what life was like for you growing up there?

Nina LaCour:

I was born and raised in a small Bay Area suburb called Moraga. It is right through the tunnel from Oakland, California. It's a really, really little town. It doesn't have a freeway exit. At first, I think I felt pretty comfortable there. And as I got older, I just felt isolated and confined by it and really longed for anonymity. So as soon as I could, I moved to San Francisco and started college there when I was 17 and went to San Francisco State, which was the opposite where I was from. It was still the Bay Area but a big public school, largely a commuter school. It was super diverse in every way possible, and the big lecture hall settings where I could just be one person in a theater listening to someone really smart talk about something they were passionate about. And it was exactly where I wanted to be.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When you're growing up, it felt, did you feel like very known like, "Hey, there's Nina"? Is that what the kind of community it was?

Nina LaCour:

Definitely. It was really small. I went largely with the same kids from elementary school through high school. I never felt like I really belonged there even though I was known there, and I'm still unpacking that and exploring why. There were some very obvious reasons. It's a very, very affluent town. It's a town where almost everybody owns their own homes. My parents moved there when my mom was pregnant with me. They had no roots there. We didn't buy a house. We rented a couple apartments over the years, and there was even a term "apartment kids" and I was one of the apartment kids. There were that few apartments there. So I definitely felt on the outskirts in that way. It was very country clubby. And then also kids did sports and I never did sports, but that was a real source of community there too. And I was just this quiet outsider feeling artsy, dreamy kid. And even though I knew everybody, I didn't quite feel like I knew where I belonged.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Where you bullied as a kid or did you just feel outside of it? I don't know. Was school a safe space for you?

Nina LaCour:

I wasn't bullied, no. I always had a close friend or a few more. I wouldn't say I was picked on, but I think that I was very, very shy, incredibly shy, and had trouble talking in class. And I also struggled academically in school, which made me feel inadequate and kind of confused. I'm certain I have some undiagnosed learning disabilities that just flew under the radar because I didn't do poorly enough. I didn't fail things, but I certainly did not excel. It's been very interesting. I have a 10-year-old, and so looking back on elementary school and what that was like and seeing some similar experiences reflected has been just very fascinating. And as you, for all of your listeners and you who have children, I feel like it's this portal to reexamining what we were like at that age. It just brings me closer to childhood all the time, having her and witnessing her experiences.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You said you had maybe some learning differences that were never diagnosed, but were you a big reader and writer? Did you like to do those things from a young age?

Nina LaCour:

Yes, definitely. I loved reading. And as soon as I could read, I was reading constantly. And writing was always my thing. Storytelling always was. I would dictate stories before I knew how to write them. I wrote poetry all the time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What do you mean you dictate them?

Nina LaCour:

To my parents. I would say, "Here's my story," and I would say it out loud and they would write it down. But storytelling has just been the way that I engage with the world, and reading too. It's always been a core part of who I am.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Got it, okay. And so were your parents big readers?

Nina LaCour:

They were readers, for sure. In the apartment where I grew up, we had our dining room table and this little alcove off the kitchen and living room, and the whole wall was a bookshelf. And there were always books coming in and out, but there were also books that just were fixtures on this bookshelf and I would stare at them and think about them and pick them off the shelves and when I got older, start reading them. And I feel like because we were a sit down at the dinner table type family and that every night of my childhood I'd be staring at these books as the backdrop to dinner. And I can remember their spines so clearly, that impacted me. They both read. My mom read novels all the time. My dad read the newspaper every single morning, the San Francisco Chronicle, and would also read novels sometimes and nonfiction books. And yeah, we were a big reader family, for sure.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I like that image of you of the breakfast books coming in by osmosis. Did you have any teachers who could tell that you were a good writer? I heard you tell a story. It was a heartbreaking story that you told your teacher was about to read your story and you knew that she was going to reveal that you're this great writer to the class.

Nina LaCour:

That was fifth grade. And by that time I don't remember really getting feedback on my creative writing because I think I don't remember ever being singled out as a good writer or anything like that. But yeah, fifth grade, we had a short story assignment and I was just elated. I've just been waiting for a short story assignment. All I did was do creative writing. At that time, I was reading Anna of Green Gables and The Secret Garden and all of these older books that really are very heavy in description and very wordy, and I still remember it so well. I had this vision for this story of this elderly woman sitting up in a house with a lace curtain looking down and seeing this man, approaching a young man. And I think she was going to tell him the story of her life.

So I was a fifth grader. This was a grand story that I was conceptualizing here, and I was just setting up the beginning. And I remember my teacher read it aloud and I was just terrified and so excited and I had just put so much effort into every detail and I had such a clear image in my head. And then she said, "Okay, so this is an example of too much detail." And it was so crushing. I didn't do sports. I was not an especially strong student in any way. I was not popular. What I had was that I was a reader and a writer. That was my identity. That's the only thing I ever felt good at. So having her use my story in that way was really crushing, I'm sure far more crushing than she ever would have imagined.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. But still, that's a little harsh. All right, let's move on to some of your reading life as a kid. Can you talk a little bit about some of the books that you were really drawn to when you were younger throughout elementary or middle school?

Nina LaCour:

I remember reading the Barbara Kingsolver books like The Bean Trees and Pigs in Heaven. Those were two that were on the shelf. And my dad one time in high school pulled down this anthology or I guess just a collected stories of Raymond Carver's who was a very well-respected short story writer in the '80s, and they're full of smoking and drinking and working hard and really dysfunctional relationships, and I just loved them. They're full of this sort of feeling of discontent and of almost desperation but very quiet at the same time, and there's a lot of uncertainty and ambiguity in them and they're super spare, which really drew me in. And once my dad introduced me to those stories, I just read them over and over and over again and studied them, and I feel like they were my first lessons in creative writing that were my own.

I had taken in year high, I took creative writing and stuff like that, but this was the first time that high school age where I was like, "I want to write like this. How do I do it? How does he do this? How does he create this sort of feeling?" There's a lot of really quiet moments. How do you create a quiet moment on a page is such a hard lesson to learn, I think, because you have to fill it with words but you also want it to have this feeling. And so I studied him and then I wrote all these short stories that were just Raymond Carver rip-offs, which are, it's very funny. But some of his style, I think, still does linger in my work in some ways.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's not hard to see that inspiration in Nina's work. In each page, paragraph, and sentence, there is an active choice to be sparse, to be intentional with every word. There's no over-complicating or diluting the power of the moment, allowing us to slow down and appreciate the depth of it. Nina's skill in this style is evident. It made me wonder if this careful and intentional observant behavior is something that goes back to her childhood. I asked her about it.

Nina LaCour:

Oh yes, yes. I feel like all I did was observe. I feel like I really had trouble just understanding what was happening in the world. I just felt like a lost... I was just searching for cues constantly. And my favorite thing to do would be to just sit and write and look at the world and write and slowly get ideas and be inspired. And I loved eavesdropping and hearing how people spoke to each other and engaged with each other. And recently, I've been doing, I did a few little free events for kid writers through the San Francisco Library and I would take them on a little walk and tell them, "We're going to look and we're going to see what you want to put in your stories and we're going to listen and we're going to eavesdrop and we're going to spy on people." That is how you become a writer, by paying attention to the world, and that's definitely what the majority of my time was spent doing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I do think that that's so much of your work. I'm thinking about, I think it's Watch Over Me. When Lee brings her breakfast, she actually speaks those words to herself, "Remember these things." And I think that is the feeling you have maybe of reading your books is like, "Remember this thing happened and that thing happened," and everything gets its own little explanation so you're not forgetting those things.

Nina LaCour:

Yeah. Thank you so much. That's such a beautiful reading of my work and what I try to do. I really appreciate that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina is acclaimed for bringing those carefully observed details and personal experiences to young adult fiction, building a world for adolescent characters that feels genuine and lived in. As it turns out, writing that way and even writing for young readers at all came about only after a discouraging misstep early in her career when she tried writing an adult book with characters much older than herself.

Nina LaCour:

I was in college, a creative writing major, and I wrote a lot of short stories. And my writing was very succinct and I didn't know how to write a novel yet at all, but I knew I wanted to write one. And I started writing these scenes and they were for an adult novel. They were adult characters. It was multi-generational. I had all these scenes. I didn't know how to turn them into a novel yet, but they did get me into Mills College where I went for grad school. And I then had the task of having to put together 40 consecutive pages for a workshop and I was like, "That is more than I've ever written." I was writing these 10 to 15-page short stories, and so I did and it wasn't good. It had some moments, but mostly it wasn't good. And it was just a horrible experience for me, just emotionally.

I held it together and then I went into the restroom and I sobbed and during the break and then I went back in and did the next person's workshop. I just felt humiliated and exposed as a fraud. It was really, really hard. And I put that novel aside for a while and I think I just wasn't ready to write it. It was too complicated for my skillset at the time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You were a baby too. You needed then... Didn't you need your life experience to write about people having a life experience?

Nina LaCour:

Totally, absolutely. Yeah, I was 21. I didn't know anything about what I was trying to write about. And so I set it aside and then I took a young adult literature class, which was great because as we were just talking about, there wasn't that much YA that was out there when I was a teenager, and I then got to go back and read the things that had been published during that time. And it was during the time in between and it was such a cool class, and I was really drawn to adolescent literature and I started writing what turned into my first novel, Hold Still, while I was in that class. And then I just kept writing YA novels.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Years later, Nina finally did get back to that original adult novel now titled Yerba Buena, thanks of all things to the COVID pandemic. And this time, with the wisdom of a few more years, she nailed it.

Nina LaCour:

I was working as a high school teacher and I had no time to just pick up this project that was not a contracted project. And so even though those characters kept living in my mind and I kept thinking, "I really do want to go back to them," I would do it a little bit between projects and then realize, "Okay, I've got to write the next real book." And then during the pandemic, suddenly there was so much time because we weren't going anywhere and I was just like, "I'm going to work on this." And I just had a few incredibly prolific months where I worked on that book. And then I wrote The Apartment House in Poppy Hill, my first chapter book, and everyone coped with that time differently and I coped with it by just writing nonstop, basically.

"She stood by the fireplace talking in that beautiful voice, which made everything she said sound like a caress to Papa who had begun to be attracted rather against his will. He never got over lending her one of his books and finding it soaked on the terrace, when suddenly she said, 'What a shame to sit indoors.' And they all went out onto the terrace and walked up and down. Peter Walsh and Joseph Breitkopf went on about Wagner. She and Sally fell a little behind. Then came the most exquisite moment of her whole life, passing a stone urn with flowers in it. Sally stopped, picked a flower, kissed her on the lips. The whole world might've turned upside down. The others disappeared. There she was, alone with Sally, and she felt that she had been given a present, wrapped up, and told just to keep it, not to look at it, a diamond, something infinitely precious wrapped up, which as they walked up and down, up and down, she uncovered or the radiance burnt through the revelation, the religious feeling.

When old Joseph and Peter faced them, 'Stargazing,' said Peter, it was like running one's face against a granite wall in the darkness. It was shocking. It was horrible, not for herself. She felt only how Sally was being mauled already, maltreated. She felt his hostility, his jealousy, his determination to break into their companionship. All this she saw as one sees a landscape in a flash of lightning. And Sally, never had she admired her so much, gallantly taking her way vanquished. She laughed. She made old Joseph tell her the names of the stars, which he liked doing very seriously. She stood there, she listened, she heard the names of the stars."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow, what a passage. Virginia Woolf really knew how to make a moment last. This passage is from her beloved work, Mrs. Dalloway, a novel that takes place over the course of a single day. By the way, Nina and her wife actually met in a course on Virginia Woolf during college.

Nina LaCour:

We had actually met a year prior, but she didn't remember me but I remembered her. She walked into a room and I was like, "Who is that?" And it was over for me. And then I waited and waited, but it's an enormous school, San Francisco State, and we didn't intersect for a year. And then she walked into Virginia Woolf class and I was elated because I had just been hoping to have another chance. We have a big poster of a painting of Virginia Woolf in our entryway.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Virginia Woolf puts the world in slow motion. In real life, time is fixed. We can be intentional about appreciating every moment as much as possible, but the frustrating part is that it will always pass just the same. It's only in retrospect that we're able to analyze and appreciate each second for what it is. In writing, we can break down a moment, put the world on pause, reflect deeply on every word, every movement. It was through encountering works like Woolf's that Nina learned to appreciate this unique ability of writing.

Nina LaCour:

Virginia Woolf is very challenging and I was trying my best to understand. And still when I read her, it takes efforts. But the thing that I just got from studying her and from reading so many, almost all of her writing in this class, was just how she does take a moment and all of these different moments, and some of them are so brief like this one, like a fleeting kiss on the lips. I picture it as such a fast, just a tiny, tiny fraction of a second, but that stays with her in a central almost to this entire book. It was the happiest moment of her life. And now we have Clarissa Dalloway in middle age throwing this party and she's remembering her youth. And this is the moment.

And there are other moments in the book and in Virginia Woolf's other novels too, where it's a very subtle thing. And not a kiss, like a feeling that passes between people or some image or something, but that's so meaningful. And I really took that with me I think in my writing and I continue to just try to reveal some of these moments in life that just change everything or make us understand things in a way that we hadn't before.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it's so true, that that is definitely reminiscent of your writing and just that deep, deep exploration. But then that moment, that landscape, that's just how fast it is but also how fast we can as people, how we, if we let ourselves, how you can dwell on or really think through something that is just a brief moment, how it can change things. You do, I think in a lot of your writing, look for those, something that is seemingly small but actually is a life-changing moment that a person realizes then or in retrospect.

Nina LaCour:

I love that you brought up that breakfast scene in Watch Over Me because I think that something like that, just being cared for, can be such an incredible moment too, and wanting to remember. I think I spend a lot of time trying to hope that I'll remember little things and how a certain simple thing felt, and writing is one way of trying to capture that feeling. Even if I'm fictionalizing it still, it's like I'm trying to capture the feeling in a way that will last.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I love that. And I love the phrase "a certain simple thing felt", it really comes across in your novels. And actually I'm curious because you've also done a picture book. Well, what led to the picture book? And did that notion, that idea of a simple thing felt, did that also still play a role in a book for a much younger audience?

Nina LaCour:

I was teaching at Hamlin University. We had so many wonderful lecturers who worked there on the faculty, and I was listening to these lectures from Phyllis Root and Jacqueline Briggs Martin, and they are just these phenomenal children's book writers. I wanted to do what they do. I really wanted to learn from them. And so I attended their lectures and I did their exercises and in a circuitous way, it led me to my first picture book called Mommy and Mama and Me in the Middle. Oh, actually it's called Mama and Mommy and Me in the Middle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I admit that I was afraid to say it because I'm like, "I don't remember which one comes first," so I'm just like, "Your picture book." But then you mess it up so it makes you feel better.

Nina LaCour:

Yes, I did.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay, go ahead. We'll link to the actual book.

Nina LaCour:

Yeah, it was called Me in the Middle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, really?

Nina LaCour:

Originally. But I love that they wanted to change it because they wanted to be very-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Clear that, yes.

Nina LaCour:

... recognizably queer parents. So it was funny because even though I've taught writing for so long and I'm always telling my students, "The way that you see the world is what you bring to your work. You don't have to write anybody else. You don't have to tell a new story. There is no such thing. It's just the way that you see the world is what makes your work special and worthy." And yet, for my own picture book, I was like, "I need to have a big concept. I need to tell the story of something big and important." And I went on this deep exploration. We had a brief time where my family lived in Martinez, California, which is where John Muir lived, the naturalist and conservationist. So we went to the John Muir house and I was learning about his daughters, and I thought, "Okay, this is great. I'm going to write a book about John Muir going out in the world and his daughters missing him."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, interesting.

Nina LaCour:

Yes. And at this time, I was spending 10 days at a time in Minnesota away from my daughter and my wife, and they missed me when I was gone. But that was the feeling that I thought that I needed something more important. And so I did all of this research and I had a manuscript and I felt really good about it. And I had read all the journals of John Muir's daughters. And then I just woke up one night and I was like, "Why am I not reading anything about the indigenous people?" And then I started doing research and I'm just like, "Oh, he was terrible to them. He wrote horrible things. In his effort to preserve land, he was also kicking people who had been the stewards of that land for an astronomically longer time than he had been there off the land." And then I was like, "I'm not writing this story." And then I still have this manuscript. And I'm like, "Okay, maybe I just write a story about our family."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They miss me.

Nina LaCour:

It was funny, but it was just like, "Oh wait, all we need is a simple story." All I need is to show a story about a kid who misses one parent while the other parent's away for work. And then once I just embraced it, I realized that's a more powerful story for a kid anyway, more recognizable, just daily life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Throughout Nina's work, the most fitting descriptor for her style, in my opinion, is undoubtedly gentle. She's masterful at digging deep and peeling back layers, but always with a soft, non-abrasive touch. She doesn't shy away from difficult subject matter. Instead, she guides the reader through it delicately and tenderly. I asked her how she felt about the word gentle describing her writing.

Nina LaCour:

The first thing that comes to me is I take writing for teenagers very seriously and for children very seriously. And I have always written about difficult topics. My first book was about suicide. I write about grief, I write about mental health, all sorts of hard things. But I have always also really wanted and cared a lot about showing also the beauty and the gentleness and the love and connection in life at the same time. Sometimes in the saddest moments of the books, I'll purposefully focus on something that's really beautiful or soft or comforting at the same time because I do think that's how life is. It just had the image of sobbing in a soft bed. It's like we don't... We're always, whether it's other people offering us comfort or us trying to comfort ourselves in some way, we find a way. Or we go out and we take a hike and we're in nature and we're feeling tremendous grief or anger or something. But it's like, "Here is the world letting us know that it's got us in some way."

And as an author, I want my readers of any age really, I do feel like, "Okay, I've got you. We're doing this, but we're doing it together." And that's where I go, I guess, as a creative person. I'm trying to not hide from the hard things but I'm also trying to offer some sort of solace at the same time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I'm thinking of so many of your books, that is one thing's happening but something else is that. I guess it's a little different though, a little different writing for adults. Did you find that, or you can be a little... The comfort doesn't have to be as strong?

Nina LaCour:

I did it, yeah. I did find that. And right now I'm nearing the second revision of my next adult novel, and it is a different experience writing for adults. We have a lot of life experience at this point, and I think some of the same tone comes through but I also do feel less of a responsibility. It's like my responsibility becomes to the book and the story and not necessarily the emotional wellbeing of my reader.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Does it feel liberating in some way? I guess-

Nina LaCour:

Oh, absolutely.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

... not feel like you have to take care of the reader as much, yeah?

Nina LaCour:

Yeah, it definitely does.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Is it growing on you, that feeling of-

Nina LaCour:

Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Like, "Let me write another one. I'm going to try this one another time."

Nina LaCour:

I love it all.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina's work has exceptional queer representation, but in an incidental way. It's not the point of the story, but it's there. And given this, I was curious about the reaction she's received from kids who read her work, especially during her school visits.

Nina LaCour:

It's changed so much over time. My first novel came out in 2009, I believe. Back then, my main character in that in Hold Still is not queer but her friend Dylan is. And when I would bring it up in school visits, there would often be an uncomfortable snicker or this feeling that it was taboo in some way. And of course, the kids react in all sorts of different ways when they're just feeling a little self-conscious or nervous or whatever. I didn't take that to be a huge homophobic statement or something. But clearly now when I talk to high schoolers, it's a totally different environment. I think that just understanding of queerness and all of the different ways that young people are identifying and expressing themselves and everything that they're open to has just shifted so much. But my favorite thing recently was I was reading Mama and Mommy and Me in the Middle at the LA Times Book Festival, a festival of books, and I had such an enthusiastic young audience. These kids were so adorable.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Especially if you've been reading the high schoolers for a lot of years.

Nina LaCour:

Exactly, exactly.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You got to do a lot to get them moving.

Nina LaCour:

Yes, yes. And I wasn't used to it at all. And I was like, "Hello, little children." And so I'm reading the book and there are these twin little guys close to the stage, and one of them's hand was just up in the air just waving and waving and waving through the whole book. And the book is just a book about the week. It's a book about missing people. And the family of three is front and center, but it is incidental queerness. It's just two parents once on the trip. The little guy, I finally call on him and he goes, "We have two moms." And he's just exploding with meaning to tell me this and it was just the sweetest thing in the world. I was like, "Yes." And we don't need to get into book banning on this, but that's just one of the things where I'm just like, "This is real life. We are all different, and this is real life. And these kids are not being exposed to anything remotely harmful and just being able to see themselves reflected or see their parents or see their friends' parents."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Their teachers' family structure.

Nina LaCour:

Family structure.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Like, "Yeah, yeah."

Nina LaCour:

Exactly, exactly. Here we are. We are real. We are here. We are not harming anybody. It just filled me with joy being able to receive that comment, hear that from this young reader.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I did have another question for you, one more question, a hard hitter. Have you always had bangs? Bangs are like, that's like your signature, so I need to know what you know.

Nina LaCour:

Yes. Okay, thank you for asking. I feel very passionately about bangs. And I had them as a child and then I think I maybe didn't have them for a while, but then in high school I got them again. And only once have I not had bangs in my adult life once I grew them out. And I used to have a chin length bob for a long time, and it was around that time I grew them out. And then I remember, well, you'll appreciate this because I don't even know where this came from, but because you live in DC. I didn't have them and I got this haircut, and I was like, "I feel like a senator's wife."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They were feathered.

Nina LaCour:

It just was not me. And then I was like, "Okay, think again."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For her reading challenge at the intersection, Nina has curated a list of books at the intersection of queerness and family.

Nina LaCour:

Sometimes when we're looking at children's literature and queerness, I think sometimes the queer family stories can be skipped over. And of course, stories about sexual and gender orientation in children is important, but when children aren't really thinking very much about their own sexuality, seeing the queer family as its own element is so important. And I know for raising our daughter, there are so few depictions of families in the media at all. And so I really wanted that. But then I also thought as we grow, as people grow up, queer families start to look different. And what we even consider family can look different. And so I have started with picture books and then I've gone through adult novels as well.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, I love that.

Nina LaCour:

Because I thought, "Why not have a whole range?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I love it. And what are a couple of the books in there?

Nina LaCour:

So one is Mr. Watson's Chickens. I also wanted to include Brandy Colbert's The Only Black Girls in Town because it's a great story with two dads and it's also very much about family life. And then I have some adult ones. One is Memorial by Brian Washington, which is a fantastic look too at queerness and family. And this one, the queer characters are the adult protagonists, but it's very much about origins and family.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This episode's Beanstack featured librarian is Faith Rice Mills, librarian at Nelda Sullivan Middle School in Pasadena, Texas. She tells us a heartwarming story to remind librarians of the importance of their work even when that impact isn't so obvious.

Faith Rice Mills:

A few years ago, we had this book club for just girls called the Rebel Girls Book Club, and we called it that based on the book Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls, which is a collection of one-pagers about women who made a difference in history. And of course, we didn't exclude boys. I told them they were welcome to join if they wanted to. We didn't exclude anybody from any gender, but it was girls who showed up. Throughout the year, we read three books. They would go home and read and then we'd talk about it. And for example, one of them was One for the Murphys which is about a girl who goes into foster care.

So there was a student who came every time but she didn't really talk. I couldn't get much out of her. So I didn't know if she liked the book club, if she was learning anything. I couldn't tell because she just didn't talk. She didn't really talk to the other girls but she was there every time. So at the end of the book club, I gave them an index card and said, "Write your opinions of the book club, just giving me feedback what I can do differently next year or what you want to continue, especially if you're a fifth grader and you're coming again next year." I got the index cards back and hers said, I wrote this down, "I love this book club. It's really nice to be somewhere I can do the things I love." You don't always realize what kind of impact you're having on those kids, and I didn't think she was getting anything out of it but that is what her card said.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Nina LaCour. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading The House of Hidden Meanings by RuPaul on audiobook, which is so good, and Camp Sylvania by Julie Murphy. If you enjoyed today's episode, please show some love and give us a five-star review. It just takes a second and really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, check out all of our resources at beanstack.com and remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and bonus content. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josiah Lamberto Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.

How do you create a quiet moment on a page is such a hard lesson to learn, I think, because you have to fill it with words but you also want it to have this feeling.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour never rushes through a moment. Instead, she encourages her readers to linger in the space to contemplate and to fully experience each second. She invites us to be deep observers of the world, which is exactly what she believes makes a great writer.

Nina LaCour:

I did a few little free events for kid writers through the San Francisco Library, and I would take them on a little walk and tell them, "We're going to look and we're going to see what you want to put in your stories and we're going to listen and we're going to eavesdrop and we're going to spy on people." And that is how you become a writer, by paying attention to the world.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour's gentle and thoughtful approach to deep and complex topics have resonated with young readers and adults alike. She's known for her novels such as Hold Still, Everything Leads to You, and We Are Okay, which received the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. In this episode, she'll tell us how and why she fell in love with YA, about her admiration for writing's ability to bring out the depth in every second, and she reveals which classic 20th century novel not only influenced her writing style, but also led to her very own meet cute with a storybook ending. And of course, she tells us the origin story of her signature bangs.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators about ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways, @thereadingculturepod, and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter. All right, onto the show.

Okay. So Nina, you grew up in the Bay Area but not quite San Francisco, right? It's close by. Can you just describe what life was like for you growing up there?

Nina LaCour:

I was born and raised in a small Bay Area suburb called Moraga. It is right through the tunnel from Oakland, California. It's a really, really little town. It doesn't have a freeway exit. At first, I think I felt pretty comfortable there. And as I got older, I just felt isolated and confined by it and really longed for anonymity. So as soon as I could, I moved to San Francisco and started college there when I was 17 and went to San Francisco State, which was the opposite where I was from. It was still the Bay Area but a big public school, largely a commuter school. It was super diverse in every way possible, and the big lecture hall settings where I could just be one person in a theater listening to someone really smart talk about something they were passionate about. And it was exactly where I wanted to be.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When you're growing up, it felt, did you feel like very known like, "Hey, there's Nina"? Is that what the kind of community it was?

Nina LaCour:

Definitely. It was really small. I went largely with the same kids from elementary school through high school. I never felt like I really belonged there even though I was known there, and I'm still unpacking that and exploring why. There were some very obvious reasons. It's a very, very affluent town. It's a town where almost everybody owns their own homes. My parents moved there when my mom was pregnant with me. They had no roots there. We didn't buy a house. We rented a couple apartments over the years, and there was even a term "apartment kids" and I was one of the apartment kids. There were that few apartments there. So I definitely felt on the outskirts in that way. It was very country clubby. And then also kids did sports and I never did sports, but that was a real source of community there too. And I was just this quiet outsider feeling artsy, dreamy kid. And even though I knew everybody, I didn't quite feel like I knew where I belonged.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Where you bullied as a kid or did you just feel outside of it? I don't know. Was school a safe space for you?

Nina LaCour:

I wasn't bullied, no. I always had a close friend or a few more. I wouldn't say I was picked on, but I think that I was very, very shy, incredibly shy, and had trouble talking in class. And I also struggled academically in school, which made me feel inadequate and kind of confused. I'm certain I have some undiagnosed learning disabilities that just flew under the radar because I didn't do poorly enough. I didn't fail things, but I certainly did not excel. It's been very interesting. I have a 10-year-old, and so looking back on elementary school and what that was like and seeing some similar experiences reflected has been just very fascinating. And as you, for all of your listeners and you who have children, I feel like it's this portal to reexamining what we were like at that age. It just brings me closer to childhood all the time, having her and witnessing her experiences.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You said you had maybe some learning differences that were never diagnosed, but were you a big reader and writer? Did you like to do those things from a young age?

Nina LaCour:

Yes, definitely. I loved reading. And as soon as I could read, I was reading constantly. And writing was always my thing. Storytelling always was. I would dictate stories before I knew how to write them. I wrote poetry all the time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What do you mean you dictate them?

Nina LaCour:

To my parents. I would say, "Here's my story," and I would say it out loud and they would write it down. But storytelling has just been the way that I engage with the world, and reading too. It's always been a core part of who I am.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Got it, okay. And so were your parents big readers?

Nina LaCour:

They were readers, for sure. In the apartment where I grew up, we had our dining room table and this little alcove off the kitchen and living room, and the whole wall was a bookshelf. And there were always books coming in and out, but there were also books that just were fixtures on this bookshelf and I would stare at them and think about them and pick them off the shelves and when I got older, start reading them. And I feel like because we were a sit down at the dinner table type family and that every night of my childhood I'd be staring at these books as the backdrop to dinner. And I can remember their spines so clearly, that impacted me. They both read. My mom read novels all the time. My dad read the newspaper every single morning, the San Francisco Chronicle, and would also read novels sometimes and nonfiction books. And yeah, we were a big reader family, for sure.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I like that image of you of the breakfast books coming in by osmosis. Did you have any teachers who could tell that you were a good writer? I heard you tell a story. It was a heartbreaking story that you told your teacher was about to read your story and you knew that she was going to reveal that you're this great writer to the class.

Nina LaCour:

That was fifth grade. And by that time I don't remember really getting feedback on my creative writing because I think I don't remember ever being singled out as a good writer or anything like that. But yeah, fifth grade, we had a short story assignment and I was just elated. I've just been waiting for a short story assignment. All I did was do creative writing. At that time, I was reading Anna of Green Gables and The Secret Garden and all of these older books that really are very heavy in description and very wordy, and I still remember it so well. I had this vision for this story of this elderly woman sitting up in a house with a lace curtain looking down and seeing this man, approaching a young man. And I think she was going to tell him the story of her life.

So I was a fifth grader. This was a grand story that I was conceptualizing here, and I was just setting up the beginning. And I remember my teacher read it aloud and I was just terrified and so excited and I had just put so much effort into every detail and I had such a clear image in my head. And then she said, "Okay, so this is an example of too much detail." And it was so crushing. I didn't do sports. I was not an especially strong student in any way. I was not popular. What I had was that I was a reader and a writer. That was my identity. That's the only thing I ever felt good at. So having her use my story in that way was really crushing, I'm sure far more crushing than she ever would have imagined.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. But still, that's a little harsh. All right, let's move on to some of your reading life as a kid. Can you talk a little bit about some of the books that you were really drawn to when you were younger throughout elementary or middle school?

Nina LaCour:

I remember reading the Barbara Kingsolver books like The Bean Trees and Pigs in Heaven. Those were two that were on the shelf. And my dad one time in high school pulled down this anthology or I guess just a collected stories of Raymond Carver's who was a very well-respected short story writer in the '80s, and they're full of smoking and drinking and working hard and really dysfunctional relationships, and I just loved them. They're full of this sort of feeling of discontent and of almost desperation but very quiet at the same time, and there's a lot of uncertainty and ambiguity in them and they're super spare, which really drew me in. And once my dad introduced me to those stories, I just read them over and over and over again and studied them, and I feel like they were my first lessons in creative writing that were my own.

I had taken in year high, I took creative writing and stuff like that, but this was the first time that high school age where I was like, "I want to write like this. How do I do it? How does he do this? How does he create this sort of feeling?" There's a lot of really quiet moments. How do you create a quiet moment on a page is such a hard lesson to learn, I think, because you have to fill it with words but you also want it to have this feeling. And so I studied him and then I wrote all these short stories that were just Raymond Carver rip-offs, which are, it's very funny. But some of his style, I think, still does linger in my work in some ways.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's not hard to see that inspiration in Nina's work. In each page, paragraph, and sentence, there is an active choice to be sparse, to be intentional with every word. There's no over-complicating or diluting the power of the moment, allowing us to slow down and appreciate the depth of it. Nina's skill in this style is evident. It made me wonder if this careful and intentional observant behavior is something that goes back to her childhood. I asked her about it.

Nina LaCour:

Oh yes, yes. I feel like all I did was observe. I feel like I really had trouble just understanding what was happening in the world. I just felt like a lost... I was just searching for cues constantly. And my favorite thing to do would be to just sit and write and look at the world and write and slowly get ideas and be inspired. And I loved eavesdropping and hearing how people spoke to each other and engaged with each other. And recently, I've been doing, I did a few little free events for kid writers through the San Francisco Library and I would take them on a little walk and tell them, "We're going to look and we're going to see what you want to put in your stories and we're going to listen and we're going to eavesdrop and we're going to spy on people." That is how you become a writer, by paying attention to the world, and that's definitely what the majority of my time was spent doing.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I do think that that's so much of your work. I'm thinking about, I think it's Watch Over Me. When Lee brings her breakfast, she actually speaks those words to herself, "Remember these things." And I think that is the feeling you have maybe of reading your books is like, "Remember this thing happened and that thing happened," and everything gets its own little explanation so you're not forgetting those things.

Nina LaCour:

Yeah. Thank you so much. That's such a beautiful reading of my work and what I try to do. I really appreciate that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina is acclaimed for bringing those carefully observed details and personal experiences to young adult fiction, building a world for adolescent characters that feels genuine and lived in. As it turns out, writing that way and even writing for young readers at all came about only after a discouraging misstep early in her career when she tried writing an adult book with characters much older than herself.

Nina LaCour:

I was in college, a creative writing major, and I wrote a lot of short stories. And my writing was very succinct and I didn't know how to write a novel yet at all, but I knew I wanted to write one. And I started writing these scenes and they were for an adult novel. They were adult characters. It was multi-generational. I had all these scenes. I didn't know how to turn them into a novel yet, but they did get me into Mills College where I went for grad school. And I then had the task of having to put together 40 consecutive pages for a workshop and I was like, "That is more than I've ever written." I was writing these 10 to 15-page short stories, and so I did and it wasn't good. It had some moments, but mostly it wasn't good. And it was just a horrible experience for me, just emotionally.

I held it together and then I went into the restroom and I sobbed and during the break and then I went back in and did the next person's workshop. I just felt humiliated and exposed as a fraud. It was really, really hard. And I put that novel aside for a while and I think I just wasn't ready to write it. It was too complicated for my skillset at the time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You were a baby too. You needed then... Didn't you need your life experience to write about people having a life experience?

Nina LaCour:

Totally, absolutely. Yeah, I was 21. I didn't know anything about what I was trying to write about. And so I set it aside and then I took a young adult literature class, which was great because as we were just talking about, there wasn't that much YA that was out there when I was a teenager, and I then got to go back and read the things that had been published during that time. And it was during the time in between and it was such a cool class, and I was really drawn to adolescent literature and I started writing what turned into my first novel, Hold Still, while I was in that class. And then I just kept writing YA novels.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Years later, Nina finally did get back to that original adult novel now titled Yerba Buena, thanks of all things to the COVID pandemic. And this time, with the wisdom of a few more years, she nailed it.

Nina LaCour:

I was working as a high school teacher and I had no time to just pick up this project that was not a contracted project. And so even though those characters kept living in my mind and I kept thinking, "I really do want to go back to them," I would do it a little bit between projects and then realize, "Okay, I've got to write the next real book." And then during the pandemic, suddenly there was so much time because we weren't going anywhere and I was just like, "I'm going to work on this." And I just had a few incredibly prolific months where I worked on that book. And then I wrote The Apartment House in Poppy Hill, my first chapter book, and everyone coped with that time differently and I coped with it by just writing nonstop, basically.

"She stood by the fireplace talking in that beautiful voice, which made everything she said sound like a caress to Papa who had begun to be attracted rather against his will. He never got over lending her one of his books and finding it soaked on the terrace, when suddenly she said, 'What a shame to sit indoors.' And they all went out onto the terrace and walked up and down. Peter Walsh and Joseph Breitkopf went on about Wagner. She and Sally fell a little behind. Then came the most exquisite moment of her whole life, passing a stone urn with flowers in it. Sally stopped, picked a flower, kissed her on the lips. The whole world might've turned upside down. The others disappeared. There she was, alone with Sally, and she felt that she had been given a present, wrapped up, and told just to keep it, not to look at it, a diamond, something infinitely precious wrapped up, which as they walked up and down, up and down, she uncovered or the radiance burnt through the revelation, the religious feeling.

When old Joseph and Peter faced them, 'Stargazing,' said Peter, it was like running one's face against a granite wall in the darkness. It was shocking. It was horrible, not for herself. She felt only how Sally was being mauled already, maltreated. She felt his hostility, his jealousy, his determination to break into their companionship. All this she saw as one sees a landscape in a flash of lightning. And Sally, never had she admired her so much, gallantly taking her way vanquished. She laughed. She made old Joseph tell her the names of the stars, which he liked doing very seriously. She stood there, she listened, she heard the names of the stars."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow, what a passage. Virginia Woolf really knew how to make a moment last. This passage is from her beloved work, Mrs. Dalloway, a novel that takes place over the course of a single day. By the way, Nina and her wife actually met in a course on Virginia Woolf during college.

Nina LaCour:

We had actually met a year prior, but she didn't remember me but I remembered her. She walked into a room and I was like, "Who is that?" And it was over for me. And then I waited and waited, but it's an enormous school, San Francisco State, and we didn't intersect for a year. And then she walked into Virginia Woolf class and I was elated because I had just been hoping to have another chance. We have a big poster of a painting of Virginia Woolf in our entryway.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Virginia Woolf puts the world in slow motion. In real life, time is fixed. We can be intentional about appreciating every moment as much as possible, but the frustrating part is that it will always pass just the same. It's only in retrospect that we're able to analyze and appreciate each second for what it is. In writing, we can break down a moment, put the world on pause, reflect deeply on every word, every movement. It was through encountering works like Woolf's that Nina learned to appreciate this unique ability of writing.

Nina LaCour:

Virginia Woolf is very challenging and I was trying my best to understand. And still when I read her, it takes efforts. But the thing that I just got from studying her and from reading so many, almost all of her writing in this class, was just how she does take a moment and all of these different moments, and some of them are so brief like this one, like a fleeting kiss on the lips. I picture it as such a fast, just a tiny, tiny fraction of a second, but that stays with her in a central almost to this entire book. It was the happiest moment of her life. And now we have Clarissa Dalloway in middle age throwing this party and she's remembering her youth. And this is the moment.

And there are other moments in the book and in Virginia Woolf's other novels too, where it's a very subtle thing. And not a kiss, like a feeling that passes between people or some image or something, but that's so meaningful. And I really took that with me I think in my writing and I continue to just try to reveal some of these moments in life that just change everything or make us understand things in a way that we hadn't before.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it's so true, that that is definitely reminiscent of your writing and just that deep, deep exploration. But then that moment, that landscape, that's just how fast it is but also how fast we can as people, how we, if we let ourselves, how you can dwell on or really think through something that is just a brief moment, how it can change things. You do, I think in a lot of your writing, look for those, something that is seemingly small but actually is a life-changing moment that a person realizes then or in retrospect.

Nina LaCour:

I love that you brought up that breakfast scene in Watch Over Me because I think that something like that, just being cared for, can be such an incredible moment too, and wanting to remember. I think I spend a lot of time trying to hope that I'll remember little things and how a certain simple thing felt, and writing is one way of trying to capture that feeling. Even if I'm fictionalizing it still, it's like I'm trying to capture the feeling in a way that will last.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I love that. And I love the phrase "a certain simple thing felt", it really comes across in your novels. And actually I'm curious because you've also done a picture book. Well, what led to the picture book? And did that notion, that idea of a simple thing felt, did that also still play a role in a book for a much younger audience?

Nina LaCour:

I was teaching at Hamlin University. We had so many wonderful lecturers who worked there on the faculty, and I was listening to these lectures from Phyllis Root and Jacqueline Briggs Martin, and they are just these phenomenal children's book writers. I wanted to do what they do. I really wanted to learn from them. And so I attended their lectures and I did their exercises and in a circuitous way, it led me to my first picture book called Mommy and Mama and Me in the Middle. Oh, actually it's called Mama and Mommy and Me in the Middle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I admit that I was afraid to say it because I'm like, "I don't remember which one comes first," so I'm just like, "Your picture book." But then you mess it up so it makes you feel better.

Nina LaCour:

Yes, I did.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay, go ahead. We'll link to the actual book.

Nina LaCour:

Yeah, it was called Me in the Middle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, really?

Nina LaCour:

Originally. But I love that they wanted to change it because they wanted to be very-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Clear that, yes.

Nina LaCour:

... recognizably queer parents. So it was funny because even though I've taught writing for so long and I'm always telling my students, "The way that you see the world is what you bring to your work. You don't have to write anybody else. You don't have to tell a new story. There is no such thing. It's just the way that you see the world is what makes your work special and worthy." And yet, for my own picture book, I was like, "I need to have a big concept. I need to tell the story of something big and important." And I went on this deep exploration. We had a brief time where my family lived in Martinez, California, which is where John Muir lived, the naturalist and conservationist. So we went to the John Muir house and I was learning about his daughters, and I thought, "Okay, this is great. I'm going to write a book about John Muir going out in the world and his daughters missing him."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, interesting.

Nina LaCour:

Yes. And at this time, I was spending 10 days at a time in Minnesota away from my daughter and my wife, and they missed me when I was gone. But that was the feeling that I thought that I needed something more important. And so I did all of this research and I had a manuscript and I felt really good about it. And I had read all the journals of John Muir's daughters. And then I just woke up one night and I was like, "Why am I not reading anything about the indigenous people?" And then I started doing research and I'm just like, "Oh, he was terrible to them. He wrote horrible things. In his effort to preserve land, he was also kicking people who had been the stewards of that land for an astronomically longer time than he had been there off the land." And then I was like, "I'm not writing this story." And then I still have this manuscript. And I'm like, "Okay, maybe I just write a story about our family."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They miss me.

Nina LaCour:

It was funny, but it was just like, "Oh wait, all we need is a simple story." All I need is to show a story about a kid who misses one parent while the other parent's away for work. And then once I just embraced it, I realized that's a more powerful story for a kid anyway, more recognizable, just daily life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Throughout Nina's work, the most fitting descriptor for her style, in my opinion, is undoubtedly gentle. She's masterful at digging deep and peeling back layers, but always with a soft, non-abrasive touch. She doesn't shy away from difficult subject matter. Instead, she guides the reader through it delicately and tenderly. I asked her how she felt about the word gentle describing her writing.

Nina LaCour:

The first thing that comes to me is I take writing for teenagers very seriously and for children very seriously. And I have always written about difficult topics. My first book was about suicide. I write about grief, I write about mental health, all sorts of hard things. But I have always also really wanted and cared a lot about showing also the beauty and the gentleness and the love and connection in life at the same time. Sometimes in the saddest moments of the books, I'll purposefully focus on something that's really beautiful or soft or comforting at the same time because I do think that's how life is. It just had the image of sobbing in a soft bed. It's like we don't... We're always, whether it's other people offering us comfort or us trying to comfort ourselves in some way, we find a way. Or we go out and we take a hike and we're in nature and we're feeling tremendous grief or anger or something. But it's like, "Here is the world letting us know that it's got us in some way."

And as an author, I want my readers of any age really, I do feel like, "Okay, I've got you. We're doing this, but we're doing it together." And that's where I go, I guess, as a creative person. I'm trying to not hide from the hard things but I'm also trying to offer some sort of solace at the same time.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I'm thinking of so many of your books, that is one thing's happening but something else is that. I guess it's a little different though, a little different writing for adults. Did you find that, or you can be a little... The comfort doesn't have to be as strong?

Nina LaCour:

I did it, yeah. I did find that. And right now I'm nearing the second revision of my next adult novel, and it is a different experience writing for adults. We have a lot of life experience at this point, and I think some of the same tone comes through but I also do feel less of a responsibility. It's like my responsibility becomes to the book and the story and not necessarily the emotional wellbeing of my reader.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Does it feel liberating in some way? I guess-

Nina LaCour:

Oh, absolutely.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

... not feel like you have to take care of the reader as much, yeah?

Nina LaCour:

Yeah, it definitely does.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Is it growing on you, that feeling of-

Nina LaCour:

Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Like, "Let me write another one. I'm going to try this one another time."

Nina LaCour:

I love it all.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina's work has exceptional queer representation, but in an incidental way. It's not the point of the story, but it's there. And given this, I was curious about the reaction she's received from kids who read her work, especially during her school visits.

Nina LaCour:

It's changed so much over time. My first novel came out in 2009, I believe. Back then, my main character in that in Hold Still is not queer but her friend Dylan is. And when I would bring it up in school visits, there would often be an uncomfortable snicker or this feeling that it was taboo in some way. And of course, the kids react in all sorts of different ways when they're just feeling a little self-conscious or nervous or whatever. I didn't take that to be a huge homophobic statement or something. But clearly now when I talk to high schoolers, it's a totally different environment. I think that just understanding of queerness and all of the different ways that young people are identifying and expressing themselves and everything that they're open to has just shifted so much. But my favorite thing recently was I was reading Mama and Mommy and Me in the Middle at the LA Times Book Festival, a festival of books, and I had such an enthusiastic young audience. These kids were so adorable.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Especially if you've been reading the high schoolers for a lot of years.

Nina LaCour:

Exactly, exactly.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You got to do a lot to get them moving.

Nina LaCour:

Yes, yes. And I wasn't used to it at all. And I was like, "Hello, little children." And so I'm reading the book and there are these twin little guys close to the stage, and one of them's hand was just up in the air just waving and waving and waving through the whole book. And the book is just a book about the week. It's a book about missing people. And the family of three is front and center, but it is incidental queerness. It's just two parents once on the trip. The little guy, I finally call on him and he goes, "We have two moms." And he's just exploding with meaning to tell me this and it was just the sweetest thing in the world. I was like, "Yes." And we don't need to get into book banning on this, but that's just one of the things where I'm just like, "This is real life. We are all different, and this is real life. And these kids are not being exposed to anything remotely harmful and just being able to see themselves reflected or see their parents or see their friends' parents."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Their teachers' family structure.

Nina LaCour:

Family structure.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Like, "Yeah, yeah."

Nina LaCour:

Exactly, exactly. Here we are. We are real. We are here. We are not harming anybody. It just filled me with joy being able to receive that comment, hear that from this young reader.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I did have another question for you, one more question, a hard hitter. Have you always had bangs? Bangs are like, that's like your signature, so I need to know what you know.

Nina LaCour:

Yes. Okay, thank you for asking. I feel very passionately about bangs. And I had them as a child and then I think I maybe didn't have them for a while, but then in high school I got them again. And only once have I not had bangs in my adult life once I grew them out. And I used to have a chin length bob for a long time, and it was around that time I grew them out. And then I remember, well, you'll appreciate this because I don't even know where this came from, but because you live in DC. I didn't have them and I got this haircut, and I was like, "I feel like a senator's wife."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They were feathered.

Nina LaCour:

It just was not me. And then I was like, "Okay, think again."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For her reading challenge at the intersection, Nina has curated a list of books at the intersection of queerness and family.

Nina LaCour:

Sometimes when we're looking at children's literature and queerness, I think sometimes the queer family stories can be skipped over. And of course, stories about sexual and gender orientation in children is important, but when children aren't really thinking very much about their own sexuality, seeing the queer family as its own element is so important. And I know for raising our daughter, there are so few depictions of families in the media at all. And so I really wanted that. But then I also thought as we grow, as people grow up, queer families start to look different. And what we even consider family can look different. And so I have started with picture books and then I've gone through adult novels as well.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, I love that.

Nina LaCour:

Because I thought, "Why not have a whole range?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I love it. And what are a couple of the books in there?

Nina LaCour:

So one is Mr. Watson's Chickens. I also wanted to include Brandy Colbert's The Only Black Girls in Town because it's a great story with two dads and it's also very much about family life. And then I have some adult ones. One is Memorial by Brian Washington, which is a fantastic look too at queerness and family. And this one, the queer characters are the adult protagonists, but it's very much about origins and family.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This episode's Beanstack featured librarian is Faith Rice Mills, librarian at Nelda Sullivan Middle School in Pasadena, Texas. She tells us a heartwarming story to remind librarians of the importance of their work even when that impact isn't so obvious.

Faith Rice Mills:

A few years ago, we had this book club for just girls called the Rebel Girls Book Club, and we called it that based on the book Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls, which is a collection of one-pagers about women who made a difference in history. And of course, we didn't exclude boys. I told them they were welcome to join if they wanted to. We didn't exclude anybody from any gender, but it was girls who showed up. Throughout the year, we read three books. They would go home and read and then we'd talk about it. And for example, one of them was One for the Murphys which is about a girl who goes into foster care.

So there was a student who came every time but she didn't really talk. I couldn't get much out of her. So I didn't know if she liked the book club, if she was learning anything. I couldn't tell because she just didn't talk. She didn't really talk to the other girls but she was there every time. So at the end of the book club, I gave them an index card and said, "Write your opinions of the book club, just giving me feedback what I can do differently next year or what you want to continue, especially if you're a fifth grader and you're coming again next year." I got the index cards back and hers said, I wrote this down, "I love this book club. It's really nice to be somewhere I can do the things I love." You don't always realize what kind of impact you're having on those kids, and I didn't think she was getting anything out of it but that is what her card said.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Nina LaCour. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading The House of Hidden Meanings by RuPaul on audiobook, which is so good, and Camp Sylvania by Julie Murphy. If you enjoyed today's episode, please show some love and give us a five-star review. It just takes a second and really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, check out all of our resources at beanstack.com and remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and bonus content. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josiah Lamberto Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.