About this episode

Neal Shusterman is best known for his "Unwind Dystology" series, his Printz winning "Scythe" trilogy, and "Challenger Deep," which won the National Book Award for Young People's Literature in 2015. In this episode, he shares how getting immersed in his favorite fictional worlds inspired him to create some of his own, he’ll talk about how and why he prioritizes characters to enhance immersion, and how seriously he takes sticking to the rules of his world.

"I think it comes down to caring about character. When you care about the characters, you care about the world they live in." - Neal Shusterman

When Neal Shusterman was in college, he was told to stop building worlds and start building characters. He listened. And from then on, his worlds became more magical and deeper than ever before. As he says, when you care about characters, you care about the world they live in.

Neal’s career has revolved around incredible and fantastical lands of his creation. In these worlds, he builds rules and structures that he sticks to rigidly, even if that means following a story arc he had no intention of writing, to begin with (he tells us that story in the episode).

Getting immersed in settings unlike (and alike) our own provides crucial lessons about perspective. This outside perspective allows us to shed our preconceptions and witness characters and events in a way we would be unable to otherwise. It’s an incredibly impactful storytelling style for young readers just learning these skills, and Neal is a master at it.

***

Keep up with Jordan and The Reading Culture @thereadingculturepod and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

***

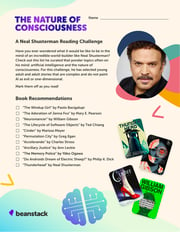

For his reading challenge, "The Nature of Consciousness," Neal wants to send us into various fictional worlds to challenge our perception of a prevailing debate in our world: A.I.

You can find his list and all past reading challenges at thereadingculturepod.com.

This episode’s Beanstack Featured Librarian is Danielle Masterson, assistant director at the Wilmington Public Library in Massachusetts. Danielle shares some wisdom to settle the debate of what qualifies as “reading”.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - The Trouble with Star Trek Blueprints (2:11)

- Chapter 2 - The Jaws of (Neal’s) Life (9:02)

- Chapter 3 - Desktop Quotes (10:32)

- Chapter 4 - Stories From the Cabin (15:14)

- Chapter 5 - No Characters, No World (18:02)

- Chapter 6 - A Sense of Hope (24:10)

- Chapter 7 - The Power of a Teacher (27:12)

- Chapter 8 - The Nature of Consciousness (30:30)

- Chapter 9 - Beanstack Featured Librarian (31:23)

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

View Transcript

Hide Transcript

Neal Shusterman:

When it all makes sense, when it all can be tracked down to something that is logical, I think readers really enjoy that because they could see how the world got there and it doesn't seem as far of a stretch, it doesn't seem like something that's just a flight of fancy. It seems like something that is extrapolated from our world down a direction that we worry it might go, or sometimes we hope it might go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal Shusterman is a masterful world builder and storyteller. His book's venture into the distant future, magical realms and alternate universes, offering readers the chance to challenge their preconceived notions of our own world while getting lost in another. Creating a place that sucks you in is no easy feat, but Neal has found the secret to making it work.

Neal Shusterman:

I think if you're all caught up in the world, you're losing the story and the characters in the story has to come first, and then you can let that world grow around them. And the world does grow. It's not something that just comes fully formed.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal Shusterman is best known for his Unwind Dystology, his Printz winning Scythe series and Challenger Deep, which won the National Book Award for Young People's Literature in 2015. In this episode, he'll tell us how his childhood obsession with details in his favorite sci-fi series ignited his passion for creating immersive settings. He'll explain why writing non fantasy for a while was crucial to his success as a fantasy writer, and he'll share a great life hack for parents and anyone else out there who has trouble coming up with new bedtime stories on demand.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways @TheReadingCulturePod, and you can also subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

I would love to first start off with what your childhood was like. What was it like to be Neal as a kid?

Neal Shusterman:

Well, I grew up in Brooklyn when Brooklyn wasn't the place to be, it was the place that you left. When I was growing up, my dream was to move out to California. I watched shows like The Brady Bunch and I wanted to have that suburban house with the AstroTurf lawn where it's always warm and it never snows and you never have to shovel snow in your driveway. But growing up I always wanted to see other places, and then I got that opportunity when my father came home one day when I was 16 and said, "Guess what? My company has transferred me. We're moving to Mexico." Two weeks later they came, took away our furniture, put us on a plane, and there I was, and I spent my junior and senior year of high school in Mexico City, which was a life-changing experience.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How so?

Neal Shusterman:

When you have an international experience, it changes your whole perspective on the world. I mean, when I first got there, I mean I experienced a lot of culture shock. I didn't speak Spanish, I had taken four years of French. But I had to learn. I went to the American school there, and so classes were taught in English, but socially most people were speaking Spanish, so I really had to pick up the language quickly. And when you've had an international experience I've found that everything else after that feels like it's easy. When I went off to college, I didn't get homesick. I was able to dare to do things that I might not normally had done because I had this experience that sort of opened up the world and didn't make anything feel like it was too difficult to do or too far to go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I've a huge believer in studying abroad and cross-cultural exchange and all of that. Let's go back though for a second. Can you tell me about what school was like for you when you were younger? What was your reading life as an elementary school kid?

Neal Shusterman:

I was a late reader. In third grade, I was the slowest reader in class and I just didn't like reading. But my third grade teacher and I did not get along, and so she used every opportunity she could to get rid of me and throw me out of the classroom. So she would just send me to the library. When she had enough of me, she would just say, "Neal, just go to the library." So I basically became the librarian's pet and the librarian would give me books that I would like. And being a non-reader, I wasn't really into books until she found books that I would like. And then reading became my thing. I would get thrown out of class on purpose to get sent to the library. And by the time that I graduated elementary school, I got the award for the best reader in school. This from a kid who was a total non-reader.

But the stories that really got me first was Roald Dahl. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I remember seeing the movie when I was, I guess, 10 years old, the original one, and then after the movie, I read the book and it occurred to me that none of this existed until Roald Dahl thought of it. He created these characters and the Oompa-Loompas in the chocolate factory and none of it was in the world until he imagined it from his mind, and now it's something that is a part of culture, something that everybody knows, and I remember saying to myself, "I want to do that."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, he was a master of that, huh? I remember Matilda was a book that I was really into. That was definitely my first book that I remember. He had some way of doing that, weaving those. So you were already thinking about that world building and creating an entire alternate reality in terms of your reading as a kid then, huh?

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah. I was always doing that, creating stories and coming up with different worlds and different realities and, "How would time travel work?" And I would come up with these entire treatises of how time travel would work when I was 11 years old, and dealing with the paradoxes and just playing with all of that. And I would write them down like they were actual documents. Every time I read a book that I loved, I would draw things from it. I was always a stickler for trying to figure out what it would look like realistically. It's like with Star Trek, when I was a kid, I would draw the plans of the Enterprise and then they actually came out with actual blueprints, and I was amazed.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How'd you do?

Neal Shusterman:

I think I did pretty good. I actually found some of the plans that I drew up for spaceships from TV shows and when I was a kid, and gosh, I was very meticulous about making sure that everything was right. I think I was more so than the actual set designers, because many times the things that they had in the sets didn't actually make sense, they didn't quite fit in the space that the ship was supposed to take up, and that always infuriated me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Could have been there one of their consultants.

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Sometimes fans, honestly, I'm sure. Have you ever had that where someone points out an inconsistency in any of the worlds you've created?

Neal Shusterman:

Yes. Yes. And my response to that was, "I meant to do that." No, there are times that there were errors. There's one point in Unwind where something that was, I think, a necklace suddenly turned into a bracelet that a character had taken and people were arguing over it about saying, "Well, he intentionally did that to show that reality is subjective." No. No. That was a mistake that nobody caught.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, right. Okay. New question. In the real world, do you believe in multiple dimensions?

Neal Shusterman:

I believe it's all possible. I think the universe is too complex for us to ever understand, and all we can do is come up with theories and come up with ideas, with the understanding that if we can come up with a really cool idea of how the universe works, then that's great because it means that the actual truth of it is even cooler than we've come up with. So when I think of things like how small I am in relation to everything to the universe, a lot of people find that to be disturbing. I find it to be comforting because it means that there's so much more, things are so much bigger than we can possibly imagine, that there is some sort of reality there that we are incapable of comprehending, and that's okay because it means that it's there.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You're the second person who's ever said that to me, and the other person was MT Anderson.

Neal Shusterman:

And I love his stuff.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It probably doesn't surprise you. Yeah, but I remember he said something to me like, "It's a great comfort." And I remember, "The great comfort you get for knowing you're a speck in the universe." And I thought everybody's frightened. He said, "No, no, no." So there you go. It's you and Tobin.

Neal's imagination is a world of its own. As a child, it kept him entertained, conjuring rules, environments, and blueprints for his favorite alternate realities and ones of his own creation. But it was a fictional New York beach he encountered as a preteen that would inspire him to tell the stories from those world.

Jaws Movie Clip:

You're going to need a bigger boat.

Neal Shusterman:

I think it was when I was in eighth grade, I read Jaws because they already had that cover, that poster, the shark coming up and the swimming one, and I got the book before the movie came out because everybody was talking about how it was going to be the big summer hit movie. And I loved the book, went to see the movie on opening day. I remember that they had to have police to block the entrance to the theater because so many people were trying to get in. That movie really defined the concept of a blockbuster movie. And I managed to get into that first matinee showing on Saturday afternoon, and I remember practically jumping over my seat at moments when the shark came out. And I walked out of that theater and I said to myself, "This is what I want to do. I want to be like Steven Spielberg. I want to be able to come up with stories that can capture people's imaginations and keep them on the edges of their seats." So that was really the moment that I really said, "Yeah, I want to do that."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Usually at this point in the show, you'll hear a single passage from a book that has inspired our guest, but Neal had to first explain to us that his brain and his computer desktop have something in common. They're both scattered with bits of information, wild ideas, and the beginnings of stories, characters and worlds. Sometimes the clutter gets in the way.

Neal, are you a person who has a lot of tabs open at one time?

Neal Shusterman:

Oh, yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Neal Shusterman:

My computer desktop has way too many windows open at any given time. When there's all these files and little snippets of things on my desktop, eventually I get very frustrated and so I put it into a file called Desktop Dump.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. There you go.

Neal Shusterman:

And then the Desktop dump has straddle like archeology, all of these things in there. There's a lot of organized disorganization on my computer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Fortunately for us, Neal's organized disorganization system includes a folder full of various quotes from authors who inspire him. He read us a few of his favorites.

Neal Shusterman:

"We do not need magic to transform our world. We carry all the power we need inside ourselves already." That's Cassandra Clare.

"Stories may well be lies, but they are good lies that say true things, and which sometimes pay the rent." That's Neil Gaiman.

"Words are, in my not so humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic." That's JK Rowling.

"Do I dare disturb the universe?", TS Elliot.

"Sometimes it's better to light a flamethrower than curse the darkness.", Terry Pratchett.

"There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.", Maya Angelou.

And the one that I'm going to conclude with is one that I've had for quite a long time, since early in my career, and this one is a quote by Flannery O'Connor that just always reminds me why I do what I do. "My task is by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel. It is before all to make you see. That and no more. And it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your desserts, encouragement, consolation, fear, charm, all you demand, and perhaps also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember when you read that?

Neal Shusterman:

I don't remember when I read it, but what I do remember is that the second that I read it, I said, "That is what I'm going to open up any speech that I give with." And so that was the opening of any presentations that I gave back earlier in my career.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Why? Why did you feel that way when you read it? What about it?

Neal Shusterman:

Just that whole idea of storytelling, being about giving readers all of the emotions, allowing you to experience all these different emotions. But also in the midst of that, have that moment of truth, that thing that transcends the story. Which is what I'm always trying to do is to write a story, I want to tell a good story, but I want something that in some way is going to transcend the words, is going to transcend the particulars of the story that I'm telling. That is always the goal. And whether I achieve that, I mean that's always up to the reader to decide. Although the things that really anchor me I have also on my desktop are some fan letters.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh yeah? Like?

Neal Shusterman:

There is one girl who is a big fan of Everlost and she wrote me to tell me that she was, and that her and her best friend would read these books and would talk about them, and then her friend got into an accident and she was basically with her friend when her friend died. And she said in the days following, she returned to reading the Everlost books and they gave her comfort. That idea that everything and everyone we feel is lost is never truly lost and the universe must somehow have a memory that we can't understand that holds on to everything and everyone, and she said it brought her great comfort. And to know that something that I wrote has comforted somebody in a situation like that. When there are moments when I'm frustrated, when I feel as if I don't know if I have it in me to write another book, I will look at those types of things and remind myself, "This is what it's about. This is why I'm doing it."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you always know that you wanted to write for young people?

Neal Shusterman:

When I was in college, I had gotten a job working as a counselor at my summer camp that I went to when I was a kid. When I came back as a counselor, I started telling stories and I got to be known as the camp storyteller and there is so much power to being a storyteller at a summer camp because the counselors would try to control these kids and they would be bouncing off the walls after they had their evening activity, all the sugar that they ate. All I had to do was walk into a cabin and they would fall silent because they knew they had 10 seconds to calm down or else I would tell my story to another cabin. So it's like my presence in the room commanded absolute silence.

But I had to come up with lots of stories to tell. Sometimes I would tell stories from movies that were out that they weren't getting to see. I remember I told Raiders the Lost Ark because that was during the summer and they didn't get to see it because they were at camp, and so I did a whole storytelling version of that. But then I would also make up my own stories and those are the ones the kids always wanted to hear again. And they would say to me, "Why don't you write that as a book? I would love to read that." And so when I went back to college into my free time, I would write those stories into books. And the first two were never published, but the third one was The Shadow Club, and that was the first book of mine that was published. And that's what got me into writing for teenagers was being a storyteller at summer camp.

To this day, I am still in touch with quite a few of the kids. They're not kids anymore, they're in their 40s and 50s, but I'm still in touch with them. They still remember the stories. One of them actually, I visited him, he lives in Miami now, and he presented to me one of the xerox bound copies of one of those books that I had written that I had just made copies and given it out to them that following summer and he still had it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, that's pretty amazing. That's really the beginning, the opening of your career. Are there some other untold Neal Shusterman stories?

Neal Shusterman:

There was a time travel story that I had come up with my second year, and that was the one that I told a lot, and the thing is, it didn't make any sense. The logic, I was just not very good at world building, and so everything was convenient and I broke the rules whenever it was inconvenient that I set up a rule. In retrospect, looking back, world building is not just something that you just do. You have to learn by error and figure out what works and what doesn't work and what loses readers and what makes your world incomplete, what keeps your world from gelling. A lot of the times with world building? It's not, it's knowing what you've done wrong in the past.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How did you learn that? At school or through practice, through telling stories to your own kids?

Neal Shusterman:

Practice.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay.

Neal Shusterman:

It was the storytelling and the practice. Those first two books and all the stories that I told at camp, with the exception of The Shadow Club, were all science fiction and fantasy stories. I had a professor in college, Oakley Hall, who ran the UCI writing program, which at the time was the premier writing program in the country. But it was a graduate program. I was an undergrad. But my majors were psychology and theater. But even so, I took every single creative writing course that the School of Humanities offered until there was no more creative writing courses for me to take.

And Oakley Hall said, "Well, why don't you sit in and audit my graduate classes?" I got to sort of be mentored by the guru of writing at the UC Irvine writing program, and he told me that I need to stop writing science fiction and stop all this world building. And I asked him why. And he said, "Because that's what you've already been doing. If you want to grow as a writer, you have to be willing to work on the things that you're not as comfortable with. You have to write genres that you've never written before. You have to practice these other aspects of writing and then you'll get better at that."

And sure enough, I followed that. The Shadow Club was not science fiction. My first few novels were not science fiction or fantasy. Then when I came back with The Eyes of Kid Midas to write a story that was a fantastical story, suddenly the characters were much more real, that you cared about them more. It wasn't all about the bells and whistles, it was about ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. I became a much better writer by not world building.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So interesting.

Neal Shusterman:

And then bit by bit, my skill at world building just grew with each book that I wrote that sort of dipped my toe back into it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Sort of like you needed those characters to feel very grounded, like you know who they are, then you can build the world around them.

Neal Shusterman:

I think if you're all caught up in the world, you're losing the story and the characters in the story has to come first, and then you can let that world grow around them. And the world does grow. It's not something that just comes fully formed. Many times, it's asking questions and finding the flaws in the world. Finding, 'Well, if I set up this, then that means that this other thing can't happen." So then I have to change what happened or I have to change what I set up. And sometimes you get stuck with rules that you've set up that you have to figure out how to live with them.

A great example of that is in Everlost. Everlost is a story about these kids, they've had a head-on collision, and so technically they've died and they've gone down that tunnel towards the light, but they bumped into each other, they knocked each other out of the tunnel, and now they're in a world that is in between life and death. I had to create this world in between life and death, and I had to try to make it different from other limbo between life and death types of stories because I didn't want to be anything that was derivative of things we've seen before. So one of the rules in the world is that how you die is how you're stuck. One of the characters was eating chocolate when he died. He ended up with chocolate smudged in his face, and initially it was just a gag. But another rule in Everlost is that the longer you're there, the less you remember about what you look like. And so things start to change, but the things that are stuck with you, the things you can't stop thinking about, those things start to take over.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh wow.

Neal Shusterman:

And I realized that this kid with chocolate on his face, that chocolate is eventually going to take over his entire body.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay.

Neal Shusterman:

And now I was stuck with this rule, how do I deal with that? And it ended up becoming one of the key parts of the story, when it just began as a gag and then something that I was stuck with because of a rule that I set up that I couldn't change because it was already published in the first book, so I couldn't change it. And I figured out how to use it and it became a crucial part of the story.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's interesting because you must have to have so much rigor around knowing exactly what the rules of the world are. And at the same time you have to have so much openness and non discipline or whatever the alternative to that is to see where that's going to take, to allow it to take you someplace.

Neal Shusterman:

I think this all comes back to those drawings of spaceships and making sure that they made absolute perfect sense. If there's something in a world that I'm building that doesn't gel, that doesn't work, I can't let it go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I mean you do pay incredible attention to these details, which obviously with the fan base of teens checking your consistency like that bracelet that you mentioned, it's very important. But I guess do you think that your respect for the rules that you create and the intricacies of these worlds are why your fans are just so attached to your stories?

Neal Shusterman:

I think it comes down to caring about the characters. When you care about the characters, you care about the world that they live in. And when the world makes sense, when everything that's happening in the world, when all the rules come from something, when you see why, "Oh, this is why this is happening in the story." When it all makes sense, when it all can be tracked down to something that is logical, I think readers really enjoy that because they could see how the world got there and it doesn't seem as far of a stretch, it doesn't seem like something that's just a flight of fancy. It seems like something that is extrapolated from our world down a direction that we worry it might go, or sometimes we hope it might go.

The basic idea behind Scythe was to tell a story that was the opposite of a dystopian story, to tell a story about what are the consequences of actually achieving the things we truly and honestly want to achieve. Rather than our worst case scenarios, our best case scenarios. There are going to be consequences to that. How do we deal with the consequences of our best case scenarios?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Speaking of best case scenarios, I've read a lot about how you always strive to keep a sense of hope in your books.

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah, I am definitely not about hopelessness. I get very frustrated with stories that end in futility because, as a writer, I think our point is to bring something into the world that in some small way makes the world better. And to put something that leaves you in a darker place than when you started is not helpful. So if I'm going to take a difficult subject, I'm going to try to find a way to leave you at the end of that story feeling as if, yes, you've gone through the ringer, you've had a difficult experience, but you're better for it. And so it's always in my mind to leave readers with hope.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That holistic approach to world building and this very hopeful lens that you have is a unique combination. And I know that you're Jewish. I am too. And I was curious if you think religion has had an impact at all on your writing?

Neal Shusterman:

I've been told by people that a lot of my books feel very Talmud-ic. Unwind and Scythe, looking at these questions of ethics and morality and consciousness and trying to look at all different angles. I think that's just part of who I am. What excites me about writing is trying to look at things from perspectives that we haven't seen before and trying to just look at a situation, even if it's a fictional or fantastical situation from every possible angle. Because I try to write stories that reflect on our world and our issues that we're facing as a culture and a species, and I try to see it from just as many different angles. Because the more perspective you can gain in a situation, the better your choices and your decisions will be, so I'm always trying to look for that point of view that hasn't been seen.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

On the topic of the Scythe trilogy, my son Cassius blew through those books. In the book's world, humanity has conquered it all, hunger, disease, war, and even death. Individuals called Scythes are those who glean or end others' lives in order to keep the population under control. For all of you Neal fans out here, Cassius drew a new tidbit out of him when he had the chance to ask a question.

Cassius:

Which Scythe do you think would be the best leader of this country or president?

Neal Shusterman:

Oh, that's a great question. I have pat answers for when people ask me, "What Scythe would you be?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You're Vonnegut. You said you're Vonnegut.

Neal Shusterman:

Yes, yes, I'd be Scythe Vonnegut. I have an answer to that question. But what Scythe would be best to lead the world? I would have to say Scythe Faraday because Scythe Faraday was, for me, the model Scythe. He was everything that a Scythe was supposed to be. So I think that would be my answer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You probably get a lot of questions like that because you visit so many classrooms. And I was wondering if you have any experiences with students that have just really stuck with you?

Neal Shusterman:

I do a lot of school visits and it's always rewarding when kids will come up to me and say, "I never liked reading until I read Scythe or Unwind or Full Tilt." And then saying, "And now I can't stop reading." To know that something that I wrote turned kids into readers. I love hearing that. One of my favorite things at a school visit was a student came up to me with a teacher and you could tell the student was hanging very close to the teacher and the teacher said, "TJ wants to ask you a question." I think it was TJ or it was initials. And the kid asked a question, it was about the book Full Tilt, and he asked a question and I responded, and everybody around was amazed and I thought, "Well, what? What's the big deal?" And they say, "No, no, you don't understand. TJ is severely autistic. He doesn't ask anybody questions. But something about your book got him to come forward and actually ask a question to you." I thought, "Wow." The idea that writing words can do things like that, and I never take that for granted.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it really is like a magical power, honestly, when you hear something like that, something that can connect like that. That's incredible. And what a teacher too, for the teacher to provide that sort of level of encouragement. What kind of impact did your teachers have on you and your career?

Neal Shusterman:

I have had teachers all along. My high school art teacher, my ninth grade English teacher, my elementary school librarian, Oakley Hall at UC Irvine. Teachers have had a profound influence over my career and my life, and I think we can all, every single one of us, think back to teachers that changed the course of our life and made a huge difference. But many times we don't hear those stories. The teachers don't hear from those kids that went out and went on to do great things because they were inspired by that teacher. But I think it's important that teachers know that the importance that they have in their students' lives.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it is, it's so important. I taught for a few years, but I think those teachers who I gave a talk one time and I remember my third grade teacher and my sixth grade math teacher, they all came to that when I was in Des Moines, and it was so cool. Really, I'm thinking they did so much and it's so thankless most of the time. So to have a student to know that, "You're the ninth reading English teacher for Neal Shusterman who went on to write..." I don't know how many novels you've written, like 50? How many have you written? How many books have you written?

Neal Shusterman:

53.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

53?

Neal Shusterman:

Up to 53. Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you have a life's goal, is there a number you're going to be like, "You know what?"

Neal Shusterman:

No, I'm going to keep on doing it until they pry that [inaudible 00:30:24] from my cold dead fingers. So whatever number that is.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For Neal's reading challenge, The Nature of Consciousness, he once again encouraged us to dive into Imagine settings in order to explore humanity, this time while also confronting a current prevailing issue in our own world, AI.

Neal Shusterman:

I thought it would be fun to do a reading challenge that was stories about artificial intelligence and also dealt with the nature of consciousness and just pondered those subjects. I tried to pick stories that were not stories that painted the evil AI in this one dimensional way. So the challenge is to read stories that are AI stories and stories about the nature of consciousness. And I try to include also young adults as well as adult.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal has curated a reading list that you can find at thereadingculturepod.com. This episode's Beanstack featured librarian is Danielle Masterson, assistant director at the Wilmington Public Library in Massachusetts. Danielle is one of those clients who has become a friend over the years of working together. She had some wisdom to share about what qualifies as reading, and settles any debate on this topic.

Danielle Masterson:

I remember, I think it was my first year with you guys at Beanstack, we had a family who they came in and they said, "Can we count our audiobooks?" We were doing Read and Bead. And they said, "What we do is we don't watch TV, we read audiobooks, and we will put an audiobook on while the kids are playing or while they're cleaning their rooms." And stuff like that. And I said, "That absolutely counts." So the kids were listening to their audiobooks. They had mom's old radio, it was a CD player. They would pick up their audiobooks. And I remember staff saying to me, "Well, these kids are getting hundreds of hours. It doesn't count." And I said, "No, it counts." Reading is reading, and as long as someone is interacting with a text in some way, they're getting the benefit of reading.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Neal Shusterman. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading Foster by Claire Keegan, recommended by Matt Dellapina, and The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams, by Daniel Nayeri. If you enjoyed today's show, please show some love and give us a five star review. It just takes a second, and it really, really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture. You can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com, and remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and insights. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media, and script edited by Josiah Lamberto-Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.

When it all makes sense, when it all can be tracked down to something that is logical, I think readers really enjoy that because they could see how the world got there and it doesn't seem as far of a stretch, it doesn't seem like something that's just a flight of fancy. It seems like something that is extrapolated from our world down a direction that we worry it might go, or sometimes we hope it might go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal Shusterman is a masterful world builder and storyteller. His book's venture into the distant future, magical realms and alternate universes, offering readers the chance to challenge their preconceived notions of our own world while getting lost in another. Creating a place that sucks you in is no easy feat, but Neal has found the secret to making it work.

Neal Shusterman:

I think if you're all caught up in the world, you're losing the story and the characters in the story has to come first, and then you can let that world grow around them. And the world does grow. It's not something that just comes fully formed.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal Shusterman is best known for his Unwind Dystology, his Printz winning Scythe series and Challenger Deep, which won the National Book Award for Young People's Literature in 2015. In this episode, he'll tell us how his childhood obsession with details in his favorite sci-fi series ignited his passion for creating immersive settings. He'll explain why writing non fantasy for a while was crucial to his success as a fantasy writer, and he'll share a great life hack for parents and anyone else out there who has trouble coming up with new bedtime stories on demand.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways @TheReadingCulturePod, and you can also subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

I would love to first start off with what your childhood was like. What was it like to be Neal as a kid?

Neal Shusterman:

Well, I grew up in Brooklyn when Brooklyn wasn't the place to be, it was the place that you left. When I was growing up, my dream was to move out to California. I watched shows like The Brady Bunch and I wanted to have that suburban house with the AstroTurf lawn where it's always warm and it never snows and you never have to shovel snow in your driveway. But growing up I always wanted to see other places, and then I got that opportunity when my father came home one day when I was 16 and said, "Guess what? My company has transferred me. We're moving to Mexico." Two weeks later they came, took away our furniture, put us on a plane, and there I was, and I spent my junior and senior year of high school in Mexico City, which was a life-changing experience.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How so?

Neal Shusterman:

When you have an international experience, it changes your whole perspective on the world. I mean, when I first got there, I mean I experienced a lot of culture shock. I didn't speak Spanish, I had taken four years of French. But I had to learn. I went to the American school there, and so classes were taught in English, but socially most people were speaking Spanish, so I really had to pick up the language quickly. And when you've had an international experience I've found that everything else after that feels like it's easy. When I went off to college, I didn't get homesick. I was able to dare to do things that I might not normally had done because I had this experience that sort of opened up the world and didn't make anything feel like it was too difficult to do or too far to go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I've a huge believer in studying abroad and cross-cultural exchange and all of that. Let's go back though for a second. Can you tell me about what school was like for you when you were younger? What was your reading life as an elementary school kid?

Neal Shusterman:

I was a late reader. In third grade, I was the slowest reader in class and I just didn't like reading. But my third grade teacher and I did not get along, and so she used every opportunity she could to get rid of me and throw me out of the classroom. So she would just send me to the library. When she had enough of me, she would just say, "Neal, just go to the library." So I basically became the librarian's pet and the librarian would give me books that I would like. And being a non-reader, I wasn't really into books until she found books that I would like. And then reading became my thing. I would get thrown out of class on purpose to get sent to the library. And by the time that I graduated elementary school, I got the award for the best reader in school. This from a kid who was a total non-reader.

But the stories that really got me first was Roald Dahl. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. I remember seeing the movie when I was, I guess, 10 years old, the original one, and then after the movie, I read the book and it occurred to me that none of this existed until Roald Dahl thought of it. He created these characters and the Oompa-Loompas in the chocolate factory and none of it was in the world until he imagined it from his mind, and now it's something that is a part of culture, something that everybody knows, and I remember saying to myself, "I want to do that."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, he was a master of that, huh? I remember Matilda was a book that I was really into. That was definitely my first book that I remember. He had some way of doing that, weaving those. So you were already thinking about that world building and creating an entire alternate reality in terms of your reading as a kid then, huh?

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah. I was always doing that, creating stories and coming up with different worlds and different realities and, "How would time travel work?" And I would come up with these entire treatises of how time travel would work when I was 11 years old, and dealing with the paradoxes and just playing with all of that. And I would write them down like they were actual documents. Every time I read a book that I loved, I would draw things from it. I was always a stickler for trying to figure out what it would look like realistically. It's like with Star Trek, when I was a kid, I would draw the plans of the Enterprise and then they actually came out with actual blueprints, and I was amazed.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How'd you do?

Neal Shusterman:

I think I did pretty good. I actually found some of the plans that I drew up for spaceships from TV shows and when I was a kid, and gosh, I was very meticulous about making sure that everything was right. I think I was more so than the actual set designers, because many times the things that they had in the sets didn't actually make sense, they didn't quite fit in the space that the ship was supposed to take up, and that always infuriated me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Could have been there one of their consultants.

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Sometimes fans, honestly, I'm sure. Have you ever had that where someone points out an inconsistency in any of the worlds you've created?

Neal Shusterman:

Yes. Yes. And my response to that was, "I meant to do that." No, there are times that there were errors. There's one point in Unwind where something that was, I think, a necklace suddenly turned into a bracelet that a character had taken and people were arguing over it about saying, "Well, he intentionally did that to show that reality is subjective." No. No. That was a mistake that nobody caught.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, right. Okay. New question. In the real world, do you believe in multiple dimensions?

Neal Shusterman:

I believe it's all possible. I think the universe is too complex for us to ever understand, and all we can do is come up with theories and come up with ideas, with the understanding that if we can come up with a really cool idea of how the universe works, then that's great because it means that the actual truth of it is even cooler than we've come up with. So when I think of things like how small I am in relation to everything to the universe, a lot of people find that to be disturbing. I find it to be comforting because it means that there's so much more, things are so much bigger than we can possibly imagine, that there is some sort of reality there that we are incapable of comprehending, and that's okay because it means that it's there.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You're the second person who's ever said that to me, and the other person was MT Anderson.

Neal Shusterman:

And I love his stuff.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It probably doesn't surprise you. Yeah, but I remember he said something to me like, "It's a great comfort." And I remember, "The great comfort you get for knowing you're a speck in the universe." And I thought everybody's frightened. He said, "No, no, no." So there you go. It's you and Tobin.

Neal's imagination is a world of its own. As a child, it kept him entertained, conjuring rules, environments, and blueprints for his favorite alternate realities and ones of his own creation. But it was a fictional New York beach he encountered as a preteen that would inspire him to tell the stories from those world.

Jaws Movie Clip:

You're going to need a bigger boat.

Neal Shusterman:

I think it was when I was in eighth grade, I read Jaws because they already had that cover, that poster, the shark coming up and the swimming one, and I got the book before the movie came out because everybody was talking about how it was going to be the big summer hit movie. And I loved the book, went to see the movie on opening day. I remember that they had to have police to block the entrance to the theater because so many people were trying to get in. That movie really defined the concept of a blockbuster movie. And I managed to get into that first matinee showing on Saturday afternoon, and I remember practically jumping over my seat at moments when the shark came out. And I walked out of that theater and I said to myself, "This is what I want to do. I want to be like Steven Spielberg. I want to be able to come up with stories that can capture people's imaginations and keep them on the edges of their seats." So that was really the moment that I really said, "Yeah, I want to do that."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Usually at this point in the show, you'll hear a single passage from a book that has inspired our guest, but Neal had to first explain to us that his brain and his computer desktop have something in common. They're both scattered with bits of information, wild ideas, and the beginnings of stories, characters and worlds. Sometimes the clutter gets in the way.

Neal, are you a person who has a lot of tabs open at one time?

Neal Shusterman:

Oh, yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Neal Shusterman:

My computer desktop has way too many windows open at any given time. When there's all these files and little snippets of things on my desktop, eventually I get very frustrated and so I put it into a file called Desktop Dump.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. There you go.

Neal Shusterman:

And then the Desktop dump has straddle like archeology, all of these things in there. There's a lot of organized disorganization on my computer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Fortunately for us, Neal's organized disorganization system includes a folder full of various quotes from authors who inspire him. He read us a few of his favorites.

Neal Shusterman:

"We do not need magic to transform our world. We carry all the power we need inside ourselves already." That's Cassandra Clare.

"Stories may well be lies, but they are good lies that say true things, and which sometimes pay the rent." That's Neil Gaiman.

"Words are, in my not so humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of magic." That's JK Rowling.

"Do I dare disturb the universe?", TS Elliot.

"Sometimes it's better to light a flamethrower than curse the darkness.", Terry Pratchett.

"There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.", Maya Angelou.

And the one that I'm going to conclude with is one that I've had for quite a long time, since early in my career, and this one is a quote by Flannery O'Connor that just always reminds me why I do what I do. "My task is by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel. It is before all to make you see. That and no more. And it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your desserts, encouragement, consolation, fear, charm, all you demand, and perhaps also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember when you read that?

Neal Shusterman:

I don't remember when I read it, but what I do remember is that the second that I read it, I said, "That is what I'm going to open up any speech that I give with." And so that was the opening of any presentations that I gave back earlier in my career.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Why? Why did you feel that way when you read it? What about it?

Neal Shusterman:

Just that whole idea of storytelling, being about giving readers all of the emotions, allowing you to experience all these different emotions. But also in the midst of that, have that moment of truth, that thing that transcends the story. Which is what I'm always trying to do is to write a story, I want to tell a good story, but I want something that in some way is going to transcend the words, is going to transcend the particulars of the story that I'm telling. That is always the goal. And whether I achieve that, I mean that's always up to the reader to decide. Although the things that really anchor me I have also on my desktop are some fan letters.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh yeah? Like?

Neal Shusterman:

There is one girl who is a big fan of Everlost and she wrote me to tell me that she was, and that her and her best friend would read these books and would talk about them, and then her friend got into an accident and she was basically with her friend when her friend died. And she said in the days following, she returned to reading the Everlost books and they gave her comfort. That idea that everything and everyone we feel is lost is never truly lost and the universe must somehow have a memory that we can't understand that holds on to everything and everyone, and she said it brought her great comfort. And to know that something that I wrote has comforted somebody in a situation like that. When there are moments when I'm frustrated, when I feel as if I don't know if I have it in me to write another book, I will look at those types of things and remind myself, "This is what it's about. This is why I'm doing it."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you always know that you wanted to write for young people?

Neal Shusterman:

When I was in college, I had gotten a job working as a counselor at my summer camp that I went to when I was a kid. When I came back as a counselor, I started telling stories and I got to be known as the camp storyteller and there is so much power to being a storyteller at a summer camp because the counselors would try to control these kids and they would be bouncing off the walls after they had their evening activity, all the sugar that they ate. All I had to do was walk into a cabin and they would fall silent because they knew they had 10 seconds to calm down or else I would tell my story to another cabin. So it's like my presence in the room commanded absolute silence.

But I had to come up with lots of stories to tell. Sometimes I would tell stories from movies that were out that they weren't getting to see. I remember I told Raiders the Lost Ark because that was during the summer and they didn't get to see it because they were at camp, and so I did a whole storytelling version of that. But then I would also make up my own stories and those are the ones the kids always wanted to hear again. And they would say to me, "Why don't you write that as a book? I would love to read that." And so when I went back to college into my free time, I would write those stories into books. And the first two were never published, but the third one was The Shadow Club, and that was the first book of mine that was published. And that's what got me into writing for teenagers was being a storyteller at summer camp.

To this day, I am still in touch with quite a few of the kids. They're not kids anymore, they're in their 40s and 50s, but I'm still in touch with them. They still remember the stories. One of them actually, I visited him, he lives in Miami now, and he presented to me one of the xerox bound copies of one of those books that I had written that I had just made copies and given it out to them that following summer and he still had it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, that's pretty amazing. That's really the beginning, the opening of your career. Are there some other untold Neal Shusterman stories?

Neal Shusterman:

There was a time travel story that I had come up with my second year, and that was the one that I told a lot, and the thing is, it didn't make any sense. The logic, I was just not very good at world building, and so everything was convenient and I broke the rules whenever it was inconvenient that I set up a rule. In retrospect, looking back, world building is not just something that you just do. You have to learn by error and figure out what works and what doesn't work and what loses readers and what makes your world incomplete, what keeps your world from gelling. A lot of the times with world building? It's not, it's knowing what you've done wrong in the past.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

How did you learn that? At school or through practice, through telling stories to your own kids?

Neal Shusterman:

Practice.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay.

Neal Shusterman:

It was the storytelling and the practice. Those first two books and all the stories that I told at camp, with the exception of The Shadow Club, were all science fiction and fantasy stories. I had a professor in college, Oakley Hall, who ran the UCI writing program, which at the time was the premier writing program in the country. But it was a graduate program. I was an undergrad. But my majors were psychology and theater. But even so, I took every single creative writing course that the School of Humanities offered until there was no more creative writing courses for me to take.

And Oakley Hall said, "Well, why don't you sit in and audit my graduate classes?" I got to sort of be mentored by the guru of writing at the UC Irvine writing program, and he told me that I need to stop writing science fiction and stop all this world building. And I asked him why. And he said, "Because that's what you've already been doing. If you want to grow as a writer, you have to be willing to work on the things that you're not as comfortable with. You have to write genres that you've never written before. You have to practice these other aspects of writing and then you'll get better at that."

And sure enough, I followed that. The Shadow Club was not science fiction. My first few novels were not science fiction or fantasy. Then when I came back with The Eyes of Kid Midas to write a story that was a fantastical story, suddenly the characters were much more real, that you cared about them more. It wasn't all about the bells and whistles, it was about ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. I became a much better writer by not world building.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So interesting.

Neal Shusterman:

And then bit by bit, my skill at world building just grew with each book that I wrote that sort of dipped my toe back into it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Sort of like you needed those characters to feel very grounded, like you know who they are, then you can build the world around them.

Neal Shusterman:

I think if you're all caught up in the world, you're losing the story and the characters in the story has to come first, and then you can let that world grow around them. And the world does grow. It's not something that just comes fully formed. Many times, it's asking questions and finding the flaws in the world. Finding, 'Well, if I set up this, then that means that this other thing can't happen." So then I have to change what happened or I have to change what I set up. And sometimes you get stuck with rules that you've set up that you have to figure out how to live with them.

A great example of that is in Everlost. Everlost is a story about these kids, they've had a head-on collision, and so technically they've died and they've gone down that tunnel towards the light, but they bumped into each other, they knocked each other out of the tunnel, and now they're in a world that is in between life and death. I had to create this world in between life and death, and I had to try to make it different from other limbo between life and death types of stories because I didn't want to be anything that was derivative of things we've seen before. So one of the rules in the world is that how you die is how you're stuck. One of the characters was eating chocolate when he died. He ended up with chocolate smudged in his face, and initially it was just a gag. But another rule in Everlost is that the longer you're there, the less you remember about what you look like. And so things start to change, but the things that are stuck with you, the things you can't stop thinking about, those things start to take over.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh wow.

Neal Shusterman:

And I realized that this kid with chocolate on his face, that chocolate is eventually going to take over his entire body.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay.

Neal Shusterman:

And now I was stuck with this rule, how do I deal with that? And it ended up becoming one of the key parts of the story, when it just began as a gag and then something that I was stuck with because of a rule that I set up that I couldn't change because it was already published in the first book, so I couldn't change it. And I figured out how to use it and it became a crucial part of the story.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's interesting because you must have to have so much rigor around knowing exactly what the rules of the world are. And at the same time you have to have so much openness and non discipline or whatever the alternative to that is to see where that's going to take, to allow it to take you someplace.

Neal Shusterman:

I think this all comes back to those drawings of spaceships and making sure that they made absolute perfect sense. If there's something in a world that I'm building that doesn't gel, that doesn't work, I can't let it go.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I mean you do pay incredible attention to these details, which obviously with the fan base of teens checking your consistency like that bracelet that you mentioned, it's very important. But I guess do you think that your respect for the rules that you create and the intricacies of these worlds are why your fans are just so attached to your stories?

Neal Shusterman:

I think it comes down to caring about the characters. When you care about the characters, you care about the world that they live in. And when the world makes sense, when everything that's happening in the world, when all the rules come from something, when you see why, "Oh, this is why this is happening in the story." When it all makes sense, when it all can be tracked down to something that is logical, I think readers really enjoy that because they could see how the world got there and it doesn't seem as far of a stretch, it doesn't seem like something that's just a flight of fancy. It seems like something that is extrapolated from our world down a direction that we worry it might go, or sometimes we hope it might go.

The basic idea behind Scythe was to tell a story that was the opposite of a dystopian story, to tell a story about what are the consequences of actually achieving the things we truly and honestly want to achieve. Rather than our worst case scenarios, our best case scenarios. There are going to be consequences to that. How do we deal with the consequences of our best case scenarios?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Speaking of best case scenarios, I've read a lot about how you always strive to keep a sense of hope in your books.

Neal Shusterman:

Yeah, I am definitely not about hopelessness. I get very frustrated with stories that end in futility because, as a writer, I think our point is to bring something into the world that in some small way makes the world better. And to put something that leaves you in a darker place than when you started is not helpful. So if I'm going to take a difficult subject, I'm going to try to find a way to leave you at the end of that story feeling as if, yes, you've gone through the ringer, you've had a difficult experience, but you're better for it. And so it's always in my mind to leave readers with hope.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That holistic approach to world building and this very hopeful lens that you have is a unique combination. And I know that you're Jewish. I am too. And I was curious if you think religion has had an impact at all on your writing?

Neal Shusterman:

I've been told by people that a lot of my books feel very Talmud-ic. Unwind and Scythe, looking at these questions of ethics and morality and consciousness and trying to look at all different angles. I think that's just part of who I am. What excites me about writing is trying to look at things from perspectives that we haven't seen before and trying to just look at a situation, even if it's a fictional or fantastical situation from every possible angle. Because I try to write stories that reflect on our world and our issues that we're facing as a culture and a species, and I try to see it from just as many different angles. Because the more perspective you can gain in a situation, the better your choices and your decisions will be, so I'm always trying to look for that point of view that hasn't been seen.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

On the topic of the Scythe trilogy, my son Cassius blew through those books. In the book's world, humanity has conquered it all, hunger, disease, war, and even death. Individuals called Scythes are those who glean or end others' lives in order to keep the population under control. For all of you Neal fans out here, Cassius drew a new tidbit out of him when he had the chance to ask a question.

Cassius:

Which Scythe do you think would be the best leader of this country or president?

Neal Shusterman:

Oh, that's a great question. I have pat answers for when people ask me, "What Scythe would you be?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You're Vonnegut. You said you're Vonnegut.

Neal Shusterman:

Yes, yes, I'd be Scythe Vonnegut. I have an answer to that question. But what Scythe would be best to lead the world? I would have to say Scythe Faraday because Scythe Faraday was, for me, the model Scythe. He was everything that a Scythe was supposed to be. So I think that would be my answer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You probably get a lot of questions like that because you visit so many classrooms. And I was wondering if you have any experiences with students that have just really stuck with you?

Neal Shusterman:

I do a lot of school visits and it's always rewarding when kids will come up to me and say, "I never liked reading until I read Scythe or Unwind or Full Tilt." And then saying, "And now I can't stop reading." To know that something that I wrote turned kids into readers. I love hearing that. One of my favorite things at a school visit was a student came up to me with a teacher and you could tell the student was hanging very close to the teacher and the teacher said, "TJ wants to ask you a question." I think it was TJ or it was initials. And the kid asked a question, it was about the book Full Tilt, and he asked a question and I responded, and everybody around was amazed and I thought, "Well, what? What's the big deal?" And they say, "No, no, you don't understand. TJ is severely autistic. He doesn't ask anybody questions. But something about your book got him to come forward and actually ask a question to you." I thought, "Wow." The idea that writing words can do things like that, and I never take that for granted.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it really is like a magical power, honestly, when you hear something like that, something that can connect like that. That's incredible. And what a teacher too, for the teacher to provide that sort of level of encouragement. What kind of impact did your teachers have on you and your career?

Neal Shusterman:

I have had teachers all along. My high school art teacher, my ninth grade English teacher, my elementary school librarian, Oakley Hall at UC Irvine. Teachers have had a profound influence over my career and my life, and I think we can all, every single one of us, think back to teachers that changed the course of our life and made a huge difference. But many times we don't hear those stories. The teachers don't hear from those kids that went out and went on to do great things because they were inspired by that teacher. But I think it's important that teachers know that the importance that they have in their students' lives.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, it is, it's so important. I taught for a few years, but I think those teachers who I gave a talk one time and I remember my third grade teacher and my sixth grade math teacher, they all came to that when I was in Des Moines, and it was so cool. Really, I'm thinking they did so much and it's so thankless most of the time. So to have a student to know that, "You're the ninth reading English teacher for Neal Shusterman who went on to write..." I don't know how many novels you've written, like 50? How many have you written? How many books have you written?

Neal Shusterman:

53.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

53?

Neal Shusterman:

Up to 53. Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you have a life's goal, is there a number you're going to be like, "You know what?"

Neal Shusterman:

No, I'm going to keep on doing it until they pry that [inaudible 00:30:24] from my cold dead fingers. So whatever number that is.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For Neal's reading challenge, The Nature of Consciousness, he once again encouraged us to dive into Imagine settings in order to explore humanity, this time while also confronting a current prevailing issue in our own world, AI.

Neal Shusterman:

I thought it would be fun to do a reading challenge that was stories about artificial intelligence and also dealt with the nature of consciousness and just pondered those subjects. I tried to pick stories that were not stories that painted the evil AI in this one dimensional way. So the challenge is to read stories that are AI stories and stories about the nature of consciousness. And I try to include also young adults as well as adult.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Neal has curated a reading list that you can find at thereadingculturepod.com. This episode's Beanstack featured librarian is Danielle Masterson, assistant director at the Wilmington Public Library in Massachusetts. Danielle is one of those clients who has become a friend over the years of working together. She had some wisdom to share about what qualifies as reading, and settles any debate on this topic.

Danielle Masterson:

I remember, I think it was my first year with you guys at Beanstack, we had a family who they came in and they said, "Can we count our audiobooks?" We were doing Read and Bead. And they said, "What we do is we don't watch TV, we read audiobooks, and we will put an audiobook on while the kids are playing or while they're cleaning their rooms." And stuff like that. And I said, "That absolutely counts." So the kids were listening to their audiobooks. They had mom's old radio, it was a CD player. They would pick up their audiobooks. And I remember staff saying to me, "Well, these kids are getting hundreds of hours. It doesn't count." And I said, "No, it counts." Reading is reading, and as long as someone is interacting with a text in some way, they're getting the benefit of reading.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Neal Shusterman. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading Foster by Claire Keegan, recommended by Matt Dellapina, and The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams, by Daniel Nayeri. If you enjoyed today's show, please show some love and give us a five star review. It just takes a second, and it really, really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture. You can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com, and remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and insights. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media, and script edited by Josiah Lamberto-Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.