About this episode

Varian Johnson (Playing The Cards You're Dealt, The Parker Inheritance) talks about the importance of diversity extending beyond the pages of children's literature and the significance of the reader-author relationship.

"I think it's really important that readers see the people behind the book: the authors, the illustrators, the librarians, the teachers, the folks in publicity and marketing. Obviously, a young reader won't see all of that, it's just important to know that the people behind the book are people of color or look like you. That's just taking diversity and inclusion and equity to another level." - Varian Johnson

As a kid, Varian Johnson always felt connected to authors. Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume were among his early favorites. He would even write letters to Blume. But those connections were unmatched compared to Walter Dean Myers. In reading Walter Dean Myers, Varian Johnson saw himself reflected in both the characters on the pages and in the author himself.

That relationship between the reader and the author is something Varian values a great deal. Now, as an adult and author, Varian takes his role in that relationship seriously. He knows the responsibility it entails in the messages he shares and how he inspires his readers. He joins to talk about that relationship and what it means for young readers to see themselves beyond the pages.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - Varian as a Young Reader (2:36)

- Chapter 2 - If You Come Softly (8:57)

- Chapter 3 - Connecting with the Reader (11:54)

- Chapter 4 - Writing as a Black Author (15:03)

- Chapter 5 - The Author's Role in Shaping Kids' Minds (17:26)

- Chapter 6 - Varian's Favorite School Visits (19:59)

- Chapter 7 - Addressing Toxic Masculinity in "Playing The Cards You're Dealt" (23:01)

- Chapter 8 - "Drawing in Color" (27:51)

- Chapter 9 - Beanstack Featured Librarian (29:08)

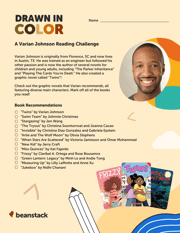

Varian's Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

Varian Johnson: I think it's really important that readers see the people behind the book. That the people behind the book are people of color or look like you. That's just taking diversity and inclusion and equity to another level.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: As readers, we often think about the connections to the characters and the story in front of us. Specifically, as we reassess representation and continue to create a new standard for diversity and inclusion in children's literature, mirror experiences are invaluable for young readers. But while those experiences are indeed invaluable, extending that mirror to include the people behind the pages is also important. For Varian Johnson, feeling that connection between himself and the author was just as impactful as seeing himself in the story.

Varian Johnson: But I just remember loving these characters in this book and the journey that the characters were on and then kind of being amazed when I realized who Walter Dean Myers was and that he was someone who looked like me and he was writing books.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Varian Johnson is an author best known for titles such as "Playing the Cards You're Dealt", "Twins", and "The Parker Inheritance". Varian's childhood discovery of Walter Dean Myers, and that behind the book representation was crucial to his own aspirations as a writer. He believes that kids seeing themselves reflected in the authors whose books they read is vital. In this episode, Varian shares more about his own experiences connecting with the authors that inspired him as a kid. He'll tell us about the importance of creating and nurturing that relationship between reader and author and also about the responsibility that comes with being the author and that relationship with young readers. Plus, on a lighter note, he reveals his favorite thing that libraries do to prepare for author visits. And at the end of the episode, Varian will share his very own Beanstack Reading Challenge, which has a focus on comics. So stick around for that.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Varian, as a young reader, what was your reading life like at home as a kid? And I kind of wonder if there were... What do you remember from that time when you were... When you would've been reading your books?

Varian Johnson: I remember being read to first, there were always picture books around. We had this book, "Make Way for Ducklings" by Robert McCloskey that we loved. And for some reason that book always is just in my mind. Is a book that my parents read to me and then that I read myself. And then as I got older, I discovered chapter books and then novels. I remember discovering books by Beverly Cleary about "Ralph S. Mouse", who rode the little toy motorcycle. And then "Ramona and Beezus", "Henry Huggins and Ribsy", anything that Beverly Cleary wrote I would read. And then a librarian said, "Well if you like these books, maybe will like these other ones." And they were books by Judy Blume. And so I was introduced to "Sheila the Great" and then the books with Peter and Fudge. And then from there I discovered Judy Blume's older books. "Iggie's House", "Blubber", "Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret". And "Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret" is still a favorite book. So certainly in my younger life, those two authors were really driving forces for me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: And sorry, you said it was a librarian who found those for you. Do you have a lot of recollections of the library, was that your public library or your school library?

Varian Johnson: It was a public library. I remember the public and the school library. I liked the public library more, I thought there were more books there and there was more access and it felt, I don't know, less judgemental. I don't know if the school librarians were judgemental necessarily. I do remember one of them saying, there was "The Outsiders", the book by S. E. Hinton. And I remember the librarian saying, "Well, you have to ask your parents permission before you could read the book." I don't even know if I wanted the book, but I remember thinking, "Well why?" And I could just go to my public library and pick it up. And I love that the public library was very encouraging for whatever book I can read. I believe in that philosophy now that a kid could read just about anything and that a young reader will self-select and they will put things down that they're not ready for.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Did you go to the library a lot? Like after school, was that sort of one of your hobs?

Varian Johnson: Every two weeks we would go to the library, my mom was really big on us going there. We would just kinda walk up and down the shelves. I remember there was the children's section and the teen section was right outside of the section in its own little area. And it was small compared to what it is today. But I remember finding some of Judy Blume's old, other books there. I'm like, "Oh, what are these doing here?" And it was "Forever" I believe or maybe "Tiger Eyes" or maybe both. And of course I read them and I loved them. I would go pretty religiously. The kids... The librarians would know me and my brother, my sister by name. And there were sometimes they would say, "Hey, there's this book that just got checked in, maybe you wanna check it out." They were always really supportive.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah. So it sounds like your mom was very involved in your reading life. I'm curious if she helped you discover Walter Dean Myers? I've heard you speak a lot about your connection with his work, especially "Motown and Didi".

Varian Johnson: That I found at my school library, actually. I remember finding it on one of those wire baskets that twirls around and I picked it up and it looked different and it looked, felt older than maybe some of the other things I was reading. And it was a cover with two black kids on it and like that, I noticed that and then maybe went to pick up the book and read it. And as I read it, I loved it and I was amazed by reading about these characters. And it was set in New York, but like a different... It was Harlem. It was a different part of New York than I had read about. I had never been there before, but I just remember loving these characters in this book and the journey that the characters were on. And then kind of being amazed when I realized who Walter Dean Myers was and that he was someone who looked like me and he was writing books. Because at this point I knew that I wanted to be a writer, but all I really knew was Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume. And I read C. S. Lewis and I had the sense they there were these famous, rich, affluent White authors who lived wherever else, and that a kid like me couldn't really be a writer, not until I discovered Walter Dean Myers. And then from Walter's books, I discovered Virginia Hamilton's books as well too. And that kind of put me on the path of certainly discovering characters who look like me, but discovering authors who look like me too and realizing that if they could write books, then maybe I could as well.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah. I wanna explore that a little more, but just first you said you knew by then you wanted to be a writer, so I'm wondering when that clicked for you.

Varian Johnson: So here's part of it. I loved the power I got from writing and I loved when I would write and someone would read it. It took a long time to show my stuff to other people, but my brother would read it and he would give lots of encouragement, and then my family and my friends. And they would laugh at what I wrote or they would find it really, really interesting or they wouldn't chastise me if it was too long. If I needed the extra time for writing a story in class, my teacher always gave me extra time, like it was... I was kind of encouraged to do this writing. And Beverly Cleary had this book, "Dear Mr. Henshaw", where this kid is writing to this author and like, "Oh yeah, I wanna, do that too. I wanna be a writer and I wanna write to an author." I remember one summer I wrote letters to Judy Blume and I wrote two letters to Judy Blume and then my cousin found them, and my cousin thought I had a girlfriend named Judy, and so I ripped up the letters, I burned them maybe even, and I realized I wasn't gonna do that again. But like the character in the book, I kind of wanted to be a writer as well too. So I was trying to figure it out in all these different ways, how could I be a writer?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: It's funny. I guess she never could have written you back if you burned them.

[music]

Varian Johnson: Chapter one, "Jeremiah was Black. He could feel it the way the sun pressed down hard and hot on his skin in the summer. Sometimes it felt like he sweated black beads of oil. He felt warm inside the skin, protected. The Fort Greene, Brooklyn where everyone seemed to be some shade of Black, he felt good walking through the neighborhood, but one step outside, just one step and somehow the weight of his skin seemed to change. It got heavier."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Jacqueline Woodson's, 1998 novel, "If You Come Softly" is essentially the love story of a young boy named Jeremiah and a young girl named Elisha. But layered beneath their blossoming relationship are the deep impacts of the identities they are both born with. Elisha is a White Jewish girl and Jeremiah is a Black boy. Woodson invokes the timeless tale of star-crossed lovers while introducing the themes of racism and social stigma. This is a novel that inspires Varian deeply, not just because of the profoundly relevant themes, but also because of the way Jeremiah is first introduced.

Varian Johnson: I love just the beginning openings of that scene because so often in a book we're talking about the cost of blackness, the trauma of blackness. I love how Jacqueline, how Woodson starts off about how he loves his skin, how he loves walking through his neighborhood, how confident he is, while also realizing as soon as he's outside of that neighborhood, outside of those warm confines, people look at him differently. He feels different, like he's aware of how society sees him and that impacts him in maybe a negative way or certainly in a way that he's aware of. But she doesn't start off with the negative. She starts off with the powerful, the beautiful, all this about his skin and walking around his neighborhood.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Do you remember when you first read it?

Varian Johnson: Yeah, I was an adult, for sure. At this point I was writing and I was trying to figure out what type of writer I wanted to be. And I had come to discover Jacqueline Woodson's work and this might have been... Well, "Locomotion" might have been the first book of hers that I read, I can't remember. This might have been the first YA novel of hers that I read and it just kind of caught me by surprise because just how beautiful it is and how it opened in that way. And I don't know if I had ever seen something written like that before, certainly not for young people, not in that way. Certainly Virginia Hamilton, the Walter Dean Myers and all these other amazing authors talked about race and culture. But I just love the way that this book just opened with it. It was really powerful.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Seeing oneself in the pages of their favorite books has an incredible impact on readers of all ages. But seeing yourself beyond the pages is an extension of that concept that means a lot to Varian. For him, it was equally important to see that the person writing those characters also looked like him. Varian already spoke a bit about the impact the reader-author relationship had on him as a reader. I was curious to hear his thoughts about that experience now that he's on the other side of it as an author.

[music]

Varian Johnson: I think it's really important that readers see the people behind the book, the authors, the illustrators, the librarians, the teachers, the folks in publicity and marketing. And obviously a young reader won't see all of that. But it is just important to know that the people behind the book are people of color or look like you. That's just taking diversity and inclusion and equity to another level.

Varian Johnson: I think the industry has done very well recently. I think we have a long way to go. I am proud of where we've come from. But it used to be where you could take a character and say they are Black, and that was considered given that there was diversity. Or you have the Black or the Korean or the Latinx best friend, let's say. And then we start expecting more of that. We want main characters of color, we want them to have their own stories, we want stories that are not just seeped in trauma and tragedy, we want happy, uplifting stories as well too. And we want a diversity of stories. And then with that, we want a diversity of authors telling these stories. We want the ability for writers to tell stories that are germane, important to their background, to their culture.

Varian Johnson: And I do think I would never tell an author what they can or cannot write. I do also think though, that lived experience counts for something. And that lived experience would trump just about any other research you can do. And I think it's important for young people to see that. I love doing school visits, I love doing school visits where someone can see who I am. And maybe their background is similar to mine, maybe they're not. But they're seeing and interacting with me as an author, as a person, as a human. I take that responsibility really seriously. I always love going to schools with primarily diverse populations. I think that's really, really important. I want them to see me and hear me talk either way. But I think it's also important for me to go to schools that aren't as diverse. I want White kids in the Midwest to see a Black guy is an author.

Varian Johnson: And I think that there's always these negative stereotypes that are associated with Black people, Black men. And I wanna dispel some of that. I don't want their first experience with a Black person to be when they're an adult when they've been fed all these mistruths, lies, misconceptions about who I am. I take that really, really seriously. I think it's really important for me to do.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: And do you feel like now that you... I mean, you've written a pretty diverse range of books in terms of the type and the topic and the way they are... And I wonder, do you feel like from a perspective of what you are expected to produce, do you feel as a Black author that you are expected to produce anything in particular?

Varian Johnson: You know, I used to. I really struggled with that. I really... I was afraid. I thought that as a Black author, I could only write "Black books". And I was afraid that these books would be marginalized and minimalized and that they would be put in a corner somewhere and they were only marketed to Black kids, which I want Black kids to read my books but I want everyone to read my books. And I hated that weight, that feeling pigeonholed, I guess. And my philosophy has changed over the years. Some of that we're talking with Jacqueline Woodson and with Rita Williams-Garcia and with all these other amazing authors. And I see it as a privilege.

Varian Johnson: You know, I love writing about Black characters and Black culture and my culture, and knowing that I don't have to be pigeonholed to do that, that I can write whatever I want to write. But I love writing about kids with backgrounds similar to mine. I think there's a place for stories like that, and I guess I take pride in that. I don't feel the weight or the burden or the responsibility of it anymore. I feel the privilege of being able to do it, the joy in being able to do it. And it really has lightened my writing as well too. I feel so much freer. And with that, I found that I can write different types of stories. It could be something a little bit heavier or it could be something lighter. I love that I can write "Twins" and "Playing the Cards You're Dealt" and "The Parker Inheritance" and all these other different books. And they have some of the same DNA, but they're all really different as well, too.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: My daughter loved "Twins" by the way. I mean she must have read it... I've never seen her read a book so many times. It just like kept coming back. Like, "You already read that."

Varian Johnson: Awesome.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: "Yes I know, I'm reading it again." Yeah, I do. And I think there is a lightness even when you are in "The Parker Inheritance" or when you're dealing with heavier topics too.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: As we've discussed a lot in this conversation so far, the relationship between author and reader is something that Varian really values. However, that relationship like any, also demands honesty and trust. As a children's author, your words can have a powerful impact on kids' ideas and their critical thinking. Varian takes that seriously. In writing about complex topics such as toxic masculinity in "Playing the Cards You're Dealt", he puts a lot of care into how he approaches these themes. I asked him to share his philosophy when it comes to the act of shaping kids' thoughts and perspectives through his stories.

[music]

Varian Johnson: My first philosophy is, don't lie to them. Don't talk down to a young reader. They're smart and they can figure it out. And they will know if you are sugarcoating it or BSing them. And it doesn't mean that it has to be dark and dreary, but it has to be truthful. And when I was writing specifically with "Playing the Cards You're Dealt", I was thinking a lot about that. How do I make this true to Ant, himself, his father? How do I end the book in a place that is realistic yet hopeful? And I don't always get it right on the first try. I had to do lots of revision on that. But when I'm revising it, I am thinking about, "What is my authorial responsibility?" And I'm not gonna say that every author hasn't had wants. Some folks don't do, like, "I only write for me and that's that and so be it." That's fine.

Varian Johnson: I am thinking about my end reader a little bit about who might be reading this book and who might benefit from this book as a mirror book where they can see their own life reflected. Or as a window book or a glass sliding-glass door book where they can see another world. And what to peek into or experience it through the safety of a book. I am thinking about those. So I'm thinking about, how do I do this in a way that is truthful but safe? A humor-like is always a good way to do that. I feel like humor dispels a lot, but I'm also never afraid of showing vulnerability as well too. I love showing vulnerable characters. I hate the idea of us not being vulnerable in a real life and not asking for help and not being afraid to show emotion. A lot of that went into writing, "Playing the Cards You're Dealt." I guess I'm always thinking about how would I want this character to exist in real life. Even if they make mistakes, who would I want them to be and can I get them at least on that path by the end of the book?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: You talked earlier about your commitment to school visits and what you bring with you in terms of your mental preparations and your potential impact on the students, but how about the reverse? Are there communities or schools that have prepared for you in ways that you really appreciate or love?

Varian Johnson: I love it when students read a book, right? I will always love if a student's familiar with me. I love if they've read, if they've been exposed to the books before I come. Sometimes a teacher or librarian will read a short story from an anthology, which works too. I just think they have some familiarity with who I am as an author, I think is really, really important. I've had a great fortune of going to some places where, The Parker Inheritance has been and all community read, so everyone in the grade will read it. Or if I'm even lucky, like there'll be adults through elementary school and they'll be all reading the book.

Varian Johnson:A Public Library or a school will make books available. And then I love those conversations, 'cause then I come in and we're talking about the book and they're asking me questions, but often it's conversation between generations as they're reading the book and what they feel about it and what they think about it. And it's really interesting to see kind of what certain generations kind of gravitate towards what they like, what resonates with them in the book. Those are really, really fulfilling. I mean, those are some of the best business where they... Where I can get a diverse group in terms of age, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, all that together, sitting down to talk about this one book. And Parker has led itself to do that really, really well. Those have been really, really rewarding.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Yeah. I love a community read when people and everybody's in on it. I've seen them like it's whole citywide community reads or, but certainly in a school if you're visiting and the parents and teachers and everybody have all been in on it.

Varian Johnson: Those are the best. Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I was thinking, it's kind of as your kids grow up, I'm looking at Howles. You have Howles sitting right behind you.

Varian Johnson: Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Okay. I think I've been pronouncing his name wrong forever and you hit me to that in something that you that I was watching of you anyways. But...

Varian Johnson: I can be, I think it's Louis Thatcher. I think it's Thatcher.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: The point is, I love that book as well, but I never read it when I was younger. I don't know why, I guess I just missed it. But we read it not too long ago aloud with our kids. Of course, my kids are now reading on their own all the time, which means you really miss out on that experience that you're speaking to now where you share reading with your kids. And it's been really refreshing for me through the podcast and just in general to every once in a while read a book together as I'm preparing for the podcast, actually I read Playing the Cards You're Dealt with Cassius and we were able to have these great conversations and pick up on completely different things we read, but also make a lot of connections about the same text.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Speaking of that shared experience as a family, Varian's novel, "Playing the Cards You're Dealt," was one of those books that fostered rich engagement and conversation in my own family, particularly with my son Cassius, who is one of the many young readers that had felt a strong attachment to Varian's characters. I felt like the story's main character, Ant took up residence in our house while he was reading the book. Ant this and Ant that. Cassius even convinced his great Aunt Dell and his dad to teach him how to play spades like Ant, he was ecstatic when I told him Varian would be joining the podcast. So I promised him that he could ask a question of his own. His first question is one that I assume many readers may have had after reading, Playing the Cards You're Dealt.

Cassius: My first question for you is how good is your spades game?

Varian Johnson: I think it's pretty good. Like I'm, I will say I'm not played super competitively in the while. My oldest daughter plays a little bit, but she can play the cards, but like they say, you know, there's swagger with her, right? Little possess, little trash talking, right? Like she's not so good at that part. So I feel like if you take my playing and my ability to do a little trash talk, I feel like I have kind of an A game. Maybe not by themselves, but together, I'm okay.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: He's got the trash talk part, though. The other question arguably more serious, although spades can be a pretty serious game, was about the theme of toxic masculinity in the book.

Cassius: What traits do you think are important for young people to have? Especially boys like me.

Varian Johnson: Boy, toxic masculinity. I think it is such a dangerous thing. I think I was explaining to maybe my daughter or maybe I was doing the school visits, and I was talking about how this philosophy that's been passed down the strongest silent type, right? And just like drilling and bearing and getting through it and like, you know, whatever it takes to survive and like, those are all great, but like there's a reason that family exists, right? And isn't it great to tell someone you need help or for them to be there to help you? I want you to do that. Like I, if you're struggling, I want you to tell me so I can help and sometimes I don't know unless you cry or show emotion. Like I can't figure it out. I just hate this idea that boys are sometimes told to just toughen up right? And just deal with it or grilling beard or whatever the case. It's so okay to cry, it's okay to show emotion. That's how we signal that we need help. And I have been trying to instill that in my kids.

Varian Johnson: My relatives, everybody I know saying, "Hey I cry. It's okay to cry, it's okay to go to therapy, it's okay to ask for help. It's okay to do all of these things, it doesn't make you any weaker, if anything it makes you strong because you're showing where you know you have strength and where you might need help, and it's okay to ask for help, it's never not okay to ask for help. And I think this is happening more and more, but I still run into pockets of places where, "The boys will be boys. You gotta act tough, you gotta man up." I just... I hate that verbiage so much because I think it's dangerous and it perpetuates.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: What were you like growing up? Did you feel like encouraged to express your emotions or did you... I mean and then what was like your...

Varian Johnson: Oh yeah, I was for sure not encouraged to express emotions I think or in different ways, right?

[laughter]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: I don't think any kids who were raised the time we were, [laughter] really like that encouraged.

Varian Johnson: Not encouraged at all, but there was this idea that the world is a dangerous, tough place. We gotta toughen you up and get ready. I remember... Again love my dad I remember him saying you know world's hard. You gotta really tough enough if you're gonna survive. And that is true but it could also be true that the world is tough and we can survive it better if we talk about it and work together to do that. I think I grew up in a time where a lot of men kind of believed that it was all on them to provide for their family and it led to mistakes. It led to risky business things right? Or gambling or drinking or doing whatever to cope with this enormous pressure on them that didn't always have to be that way. Women too there's this, whole philosophy with the song, The Strong Black Woman, right? And yes I love a strong Black woman but also you don't have to be strong by yourself, right? There's family, there's other people to lean on. We shouldn't, I hate the idea that we have to feel like we have to carry all this burden by ourselves. And if there's anything I can get young people to see is that they don't have to do it all by themselves.

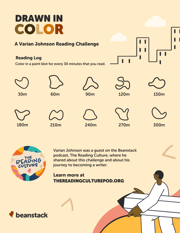

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: Again that was Varian Johnson. As you've come to know everyone that we speak to on this podcast will also provide us with their own unique reading challenge for all listeners and partners on Beanstack, Varian's challenge is called Drawn in Color. It focuses on graphic novels featuring diverse main characters and created by diverse authors.

Varian Johnson: We're in this golden age of graphic novels right? And there's so many graphic novels coming out and they're amazing and wonderful and we still don't have enough created by or featuring people of color. I will always say like, Raina Telgemeier is the Judy Blume of graphic novels. Like Raina has really opened the doors for all these other people to come into this middle grade space for doing graphic novels. But I love that we're seeing graphic novels where kids can represent their culture but not in the way that's tragic. That they're celebrating culture, this joy in their culture.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: All of our listeners can join Varian's Challenge Drawn in Color, by visiting thereadingculturepod.com. There you'll find the full list of Varian's recommended books and more details about the challenge. And before we sign off, let's give some recognition to the wonderful librarians in our Beanstack community. Today's Beanstack featured librarian is Leah Wyan, the youth fiction selector for Tulsa City County Library in Oklahoma. She told us about a recent heartwarming experience from her library featuring beloved author Jason Reynolds.

Leah Wyan: Over the course of the pandemic of course we moved to doing all of our huge programs virtually and we really missed out on some reliable connections with students and being able to take authors that we were bringing in to give them awards to schools and have them meet the students and really form personal connections. I missed that so much and I thought in early May, 2021 that we might be able to bring our award winning author that year and we weren't able to do it in person so we had to do this virtually. But of course it worked out because the author was none other than Jason Reynolds who is amazing in every form or medium or modality that you experience him, right?

Leah Wyan: So we did our big award program virtually and he met with some of the writers who had won our writing contest virtually and he met with a local high school Booker T. Washington High School, and it was such a difficult production to get it up and running and everything but he connected so deeply with those students. And a couple months later I was in one of my local independent bookstores Magic City books and I was just browsing the shelves. And I overheard a high schooler come in and ask for one of Jason Reynold's books and she said, "You know he came and visited my school well virtually but... " And she was just still so pumped up about him and about reading. And that just made me really so happy to think that all of that effort and had been worth it and that the connection still really came through even through the screen.

[music]

Jordan Lloyd Bookey: This has been the Reading Culture, and thanks again to today's guest Varian Johnson. Again I'm your host Jordan Lloyd Bookey and currently I'm reading "The Getaway" by Lamar Giles. And Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin. If you enjoyed today's show, please show some love and rate, subscribe and share the Reading Culture among your friends and networks. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's Reading Culture, you can check out all of our resources @beanstack.com. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and edited by Josiah Lamberto Egan. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode of the show. Thanks for joining and keep reading.