About this episode

Mark Oshiro was taught to fear the world. To be someone they were not and to repress someone they were. But books were an escape. Books taught them that freedom was possible.

"It's practice. Vulnerability is practice. It is learning that you can do things and say things that seem scary, but ultimately know that you're safe." - Mark Oshiro

Mark spent over a decade blogging about the stories they consumed, empathizing with characters, criticizing choices, and embracing every person's journey. But then they realized it was their turn to share, and in that sharing, they learned the transformative power of storytelling from the other side of the pages. They knew the healing power of vulnerability.

Mark debuted on the YA scene with their 2018 novel “Anger is a Gift” and has since written titles such as “Each of Us a Desert" and the latest installment in the Percy Jackson universe, “The Sun and the Star.” But their recent semi-autobiographical novel, 'Into The Light,' represents their most ultimate and vulnerable storytelling to date.

In this episode, Mark shares their life story and reflects on the refuge that books and libraries offered them as a youth from an abusive household. They also discuss how lowering their emotional defenses led them to discover the healing power of vulnerability.

***

Connect with Jordan and The Reading Culture @thereadingculturepod and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

***

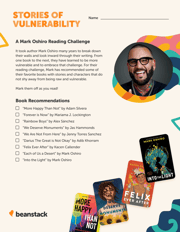

In Mark’s reading challenge, "Stories of Vulnerability," they want us to explore other stories with the same rawness they bring to their work.

You can find their list and all past reading challenges at thereadingculturepod.com.

Today’s Beanstack Featured Librarian is Cindy Philbeck, a teacher librarian at Wando High School in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She told us about her library's lunchtime strategy that encourages students to visit and see the space as a refuge.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - A Controlled Environment

- Chapter 2 - Safety in Books

- Chapter 3 - Losing Grip

- Chapter 4 - We Are Okay

- Chapter 5 - Mark Does Stuff (lots of stuff)

- Chapter 6 - The Practice of Vulnerability

- Chapter 7 - Closure?

- Chapter 8 - Stories of Vulnerability

- Chapter 9 - Beanstack Featured Librarian

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

- The Reading Culture

- The Reading Culture Newsletter Signup

- Mark Oshiro

- Mark Does Stuff

- Anger Is a Gift by Mark Oshiro | Goodreads

- We Are Okay by Nina LaCour

- Cindy Phillbeck's Library (this week’s featured librarian)

- The Reading Culture on Instagram (for giveaways and bonus content)

- Beanstack resources to build your community’s reading culture

View Transcript

Hide Transcript

Mark Oshiro:

It's practice. Vulnerability is practice. It is learning that you can do things and say things that seem scary, but ultimately know that you're safe.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In Mark Oshiro's formative years, they were taught to fear the world around them. They were isolated and controlled in all areas, but one, books. When teenage Mark eventually tried to push back against those restrictions, overnight, they found themselves alone and without a home. Mark's writing career has been a journey to accepting this traumatic past, learning to process it, and discovering the value of being open with others. Their novel, Into the Light, serves as a culmination of these discoveries so far.

Mark Oshiro:

I will say writing it was very healing. To be able to name it and say it out loud and to devise a character's journey knowing that there's light at the end of the tunnel too, it did make writing about it a lot easier than I expected when I started the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Mark is a Hugo-nominated writer, best known for Anger Is a Gift, Each of Us a Desert, the latest installment in the Percy Jackson universe, The Sun and The Star, and of course, Into the Light. They also created The Mark Does Stuff universe, which for 13 years featured blogs reviewing popular books and TV series sometimes with a little less sensitivity than Mark's more recent writing.

Mark Oshiro:

That was a moment where I was like, "Okay, Mark, if you can't just make a "My parents are dead" joke to a random stranger..."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In this episode, Mark shares their life story and reflects on the refuge that books and libraries offered them as a youth from an abusive household. They discuss how lowering their emotional defenses led them to discover the healing power of vulnerability, and we'll also learn the franchise they ripped off as a kid that kicked off their love of writing. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators about ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities.

We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways at The Reading Culture Pod, and please also subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

I know that you were adopted and that has played a really important role. So, you want to talk about your early childhood and some of your early experiences?

Mark Oshiro:

I have an identical twin brother who's based in Maryland, who is an educator. It's very interesting because we've almost switched places, because growing up, everyone was like, "Mark will be the one with five degrees and is a teacher, and Mike will be the one traveling the world with a bunch of tattoos and is a big weirdo." Somewhere in our 20s, we switched places. What's interesting about talking about being adopted as well is unfortunately, for a lot of adopted kids, we can't really piece together our childhoods. We don't have a concrete history. I know we were in foster care for at least a year, possibly two years, but we were told a story about how we were adopted and how we came into our family.

It wasn't until about two years ago that we found out that most of it wasn't true and that we were told a story that made it seem very much like our parents and in particular our mom were saviors, that they rescued us from this very dangerous, heightened situation and it just wasn't true. We've since gotten in contact with our biological mom's sister who has provided us with documents. For example, I know what my name was before I was adopted. It was Kevin. When you're raised with a story, you believe it wholeheartedly and you tell other people that story. Then it wasn't until I got in my 20s and 30s that my brother and I started not only questioning it, but other people in our life, particularly people who were social workers, people who worked in foster care.

We're like, "That doesn't make sense." Something is missing, but we were like, "Well, we don't know. We can't really provide it to you. This is what we were told."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was the story that she told you?

Mark Oshiro:

We had a drug addicted mother who was going to give us away to the streets or something, which-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The typical... Right, yeah.

Mark Oshiro:

That was adults. That's so absurd, but as a kid, you're like, "Oh, my God. The streets. What are the streets? Oh, my God. I don't want to go there." It wasn't someone she was related to, but it was like a friend of a family member who she heard through the grapevine. Very much like some of the characters in Into the Light, God told her to go save those children. So, she went through this long, lengthy, protracted adoption process and adopted us and saved us. Then the other half of it being we spent most of our childhood believing someone was trying to take us back. So, we were not allowed to have friends over to the house. No one was allowed to know where we lived. We were not allowed to do afterschool events until we were about 15 or 16 years old.

Then if we did well, she would pull us out of them, because she didn't want attention on the family. That was what the environment I was raised in, this white saviorism mixed with this very overprotective behavior, also mixed in with a very, very nationalistic sense of Christian identity. We had to mold ourselves into essentially the perfect white people, even though we weren't. What an identity crisis to be put in as a child. I remember being very young, being like, "Some of this is bullshit. This doesn't make sense. I don't understand it, but I don't have the words."

So I often think when I'm writing, how can I give words to someone who doesn't know how to describe their experience? It's why Into the Light is I feel like it's the most specific book I've ever written. I am very much speaking to that younger version of myself and saying, "You're going through this thing that doesn't make sense, and it's because it's never going to make sense."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's so odd to be a kid having to come to that realization to see things for what they are when you don't really have a way to see them for what they are. To have to come to that on your own over time, that seems hard.

Mark Oshiro:

But I like that you put it that way too, because it meant that there wasn't much magic in terms of the childhood. I certainly had positive memories, and particularly of my siblings. My twin brother and I are still best friends to this day, but it's more that when I hear other people talk about their childhoods and that idea of blissful ignorance, I got to live in a time where I didn't know there were things wrong with the world and I just got to be a kid. I'm sitting there like I don't know what that's like, because at a very, very young age, I was constantly told how the rest of the world was wrong and how many evil things were out there both in terms of society. Brown, Black people are evil, the streets, right? Yeah. That's a story of this external thing that's coming to get you.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What were your relationships with teachers and do you think that they-

Mark Oshiro:

Oh, my God.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did they ever wonder what was going on?

Mark Oshiro:

They all knew it was not a good environment at home and they could tell. Now, as an adult, I'm like, "Oh, of course, they could tell. Of course, they were cognizant of not only some of the things I might be saying in class, but I was a very shy kid." My fifth grade teacher reached out to me probably two or three years ago and was like, "You were the most frightened little boy I've ever seen in my life." I remember her telling me that the only time I lit up was when I was asked to read in class. I think that's what the teachers certainly in elementary school picked up on was here was the one thing Mark was thrilled about and was excited about and would open up.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I've heard that your mom was very encouraging of you reading no matter what it was. You said that she was a Christian nationalist, or how would you describe her?

Mark Oshiro:

So my mom was virulently anti-anyone outside of the United States. So, at home, we were told the United States is the best country and it's because we all believe in the right Jesus. Then it became well, it's only our city. Then it became well, it's only our community. By the time we're like 10 and 11, it's only our house. Nowhere else is safe. That being said, and this is a thing, my brother and I and I have a younger sister as well, who incidentally also adopted, also the same biological mom, but she has a different biological dad. We were surveilled as kids. Anything you brought into the house, it was let me make sure that that's okay with the exception of books and the X-Files and the Twilight Zone. My mom loved those shows.

So, a joke I make sometimes when I'm doing school visits is like I live this heavily regimented life, but I was allowed to watch a TV show that had literal demons on it. In my mom's mind, my interest in English and in reading and generally doing well in school would save me from the streets, would save me from this life of being destitute, addicted to drugs, in a gang, any of those things. So, while she may not have actually had a connection with me, like a deep emotional connection with me as a child, that part she was very supportive of.

She loved that I read. She loved that I was always reading. She would encourage me. I mean, we had the World Book Encyclopedias. So, sometimes she'd be like, "What letter are you going to read this month?" It was probably the only thing I ever really truly bonded with her over.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did she in surveil what books you were reading at home or did it matter? Could you take them out from your school library?

Mark Oshiro:

No.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You could read anything you wanted.

Mark Oshiro:

No, if they were in the school library for some reason, it was okay, but not music. Music, television shows, movies, no, but there was something about the written word. I mean, to give you an example, I have a much, much older sister who moved out of the house years and years before I discovered this, but I think when we were like four or five. She left behind a box of her books, and I'm eight years old sitting on the couch reading Stephen King's IT.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nuh-uh.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, that was the first adult book I ever read. I didn't truly understand it, but it gave me my love of horror and all things spooky. So, this is a podcast, so they won't be able to see this, but I do keep these on my desk. Literally, I'm holding up a laminated book I wrote. This was 1994, so it was 10 years old. It's Mark Oshiro's Goosebumps. We can also laugh. It's called Stay Out of the Closet. I love that message for myself, but I wrote 13 or 14 of these.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow.

Mark Oshiro:

But I only wrote the one and then I have another one here that my teacher was like, "You should make your own series." So I made this series. I'm holding up another one. It's called Terrifying Tales and I wrote 13 of these.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So despite the intense regulation on the rest of their life, books served as Mark's sole escape, the only place where they were able to navigate freely. However, that sole refuge would slowly slip away as they grew older. At the same time, Mark began to realize that their mother's painting of the outside world just didn't match what Mark was seeing.

Mark Oshiro:

I think part of the consciousness came from living in Southern California in a minority, majority city. I grew up in Riverside, California. I would say 60 to 70% of the kids around me were Central American. They were Mexican, El Salvadorian, Guatemalan. So, I'm finally around people who have black hair, brown skin. My brother and I are able to start speaking Spanish even though we've never learned or at least we thought we'd never learned a word of it. So, there is that consciousness that comes with, "Why is this so easy? Why do I look like these people? But I'm being told they're bad, but I'm around them every single day and I love my friends. I love who I'm around. It just doesn't make sense."

So it's that the awareness came from the contradiction of here's what I'm being told, but anytime I'm away from the house, I'm experiencing something different. So, there's this friction that's happening that forces you even at that age to start being aware, you have to start paying attention.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. How did that play out as you got older?

Mark Oshiro:

I had a very public traumatizing moment in the middle of high school, about a month into my junior year. For context for your listeners, up until that point, my first two years of high school, this idea that my mom was slowly closing what was allowed and what my brother and I were allowed to do had gotten so small that she used to go to my school and interrupt me in classes-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow.

Mark Oshiro:

... to punish me for things that I had done at home.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wait, that's so humiliating for a kid. So, she would come like when to do what? To come to your class?

Mark Oshiro:

She became known on campus and then to start denying her access because she would just walk onto campus. The first memory that came to mind was one morning she came to class to yell at me. She yelled at me for not putting clothes away correctly. Obviously, all of this is an overreaction, but a thing that I've processed with therapists is that it never was about actually doing anything wrong. I believe that she started to realize she was losing her grip on the two of us and is freaking out. So, I had this teacher who I'm still friends with on Facebook today, who I will say right now, Ms. Alford, if you're listening to this, she saved my life. She latched onto me and recognized something into me when I was a freshman. She was my freshman year English teacher.

I literally would not be able to sit here talking to you like this if it wasn't for her. She taught me public speaking. I became much more confident in myself. My mom became horribly threatened by this relationship. She very publicly pulled me out of mock trial and yelled at my teacher in front of all of my peers, because we were two minutes late during a practice once. We went over two minutes. She got so mad at Ms. Alford, she spread a rumor that Ms. Alford was sleeping with me. I give you this context to understand I'm 16 years old.

I have no friends outside of school. I'm not allowed to go anywhere. I have my first job, so I'm allowed to go to school, cross-country practice, and I have this job at a grocery store where my mom would sit in the parking lot and surveil me and watch me. If I talked to anyone, she would later ask, "Who was that? Tell me everything you said."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow. She was physically observing you.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, it came to a head, because my brother was not as surveilled but pretty heavily surveilled as I was. We devised this whole system where we... I mean, this is a very teenage thing to do. We told our mom that cross-country practice ended at 5:00 every day, and it ended at 4:00. For an extra hour, we would go to our friend's houses and just hang out with someone.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Be normal, just get to do things that kids do.

Mark Oshiro:

She caught us. I won't go into details, because it was very violent, but she abused the two of us physically, but she focused almost all of it on me. So, it was this thing where I was trying to piece together, "Why am I being the target of a lot of this?" It wasn't until she said something to me that was incredibly homophobic, and then I was like, "Oh, that's why." That day that we have this huge fight, she tells me to leave and never come back. I don't want to ever see you again. So, that was the day. If you heard it from my mom, she would say, I ran away from home, but I always believed I was kicked out because she told me to leave. I spent the remainder of high school estranged from my family.

My mom did nothing to bring me home. She never wanted me back around. It took two and a half years for me to be able to even speak to her. I had to survive high school. Either I was couch-surfing with friends. There were a few educators who put their whole careers on the line to be like, "Do you need somewhere to sleep? Knowing that this is unethical, but you don't have any other choice, so I'd rather do the thing that is nice and can help you and potentially risk my career."

They knew and I knew too, this is a big deal, but I think I lived in 20 different places by the time I graduated high school and sometimes on the street. There was a particular park that if I didn't have anywhere to go, it had this jungle gym thing that if you set up underneath, it would block any potential rain. Now since you've read Into the Light, that's where that particular heartbreak comes from and it isn't fictional. I knew what it felt like.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

If you've read Into the Light and I highly recommend it, you'll have noticed a lot of similarities with Mark's personal narrative. The book follows a young boy, Manny, who is cast out by his family and must navigate life in the road on his own. Little pieces of the novel are so physically and emotionally specific that they stayed with me long after reading.

For instance, there's this one heartbreaking scene where Manny, living with another family, painstakingly puts a towel under the door while he showers to prevent light from escaping and potentially disturbing others in the motel room. He's consumed with anxiety that the slightest mistake or imposition will get him rejected from yet another home. I asked Mark about this, and they told us it does indeed take direct inspiration from old habits.

Mark Oshiro:

That's all my routines in the places that I live thinking the little details, don't leave body hairs behind. Something just so simple as that because it's like you don't want anyone to remember that you're there and it's a thing you learn as a survival technique of. This is a very crass way of thinking about it, and I liked getting to write Manny thinking about it in that very direct way too. But once you become annoying to someone, your time in that place is up. It's true. I knew every time when I'd overstayed, I could feel it. I could sense it in the air or I'd hear a complaint about "Hey, could you not do this around the house?" I'm like, "That's strike one. I understood, I don't live here. I'm not your child." There's another character he meets on the road, Cesar, the rules.

A lot of that came from my experience of learning how to navigate houselessness as a teenager. I know now even saying that, that is sad. It is a really sad thing to have to experience at that age, but I will say writing it was very healing. To be able to name it and say it out loud and to devise a character's journey knowing that there's light at the end of the tunnel too, it did make writing about it a lot easier than I expected when I started the book, because I certainly dreaded writing certain passages or certain scenes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, my gosh. Yes. I mean, the way you wrote so many of these emotions is really raw and touching, and it just must've been such an unimaginably difficult time for you. I did wonder if you still were able to read and find that respite despite all the turmoil in your life at that time.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, I was still constantly reading as a person who was almost at the time, the library was my best friend. I associate that place with comfort, with warmth food. The librarian often had snacks behind the counter. I would just sit and just pull a book off a shelf and read, or sometimes I would go up to the librarian and just be like... You know that ridiculous thing like I want a book that is going to give me nightmares for 400 years. She's like, "I have the perfect one."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I have the one.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, I have the one.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So the library was your spot.

Mark Oshiro:

Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I would say my middle school library, my high school library, and the public library, I spent a great deal of time in. So, oftentimes that's where I would have to do homework, because I didn't have somewhere to go. I loved that feeling of wandering down the shelf and just seeing a spine that maybe looked a little weird and the color was brighter than the others and pulling it out, reading the little synopsis on the back, and being like, "I don't know what any of this is." Okay. It just was always so exciting to me. It was also books were my window to the outside world. When you live in such an insular, repressed environment, that was my chance to see what is actually going on with other people and other families.

"I've been thinking about your grandpa a lot," Mabel says. We've been sitting on the elevator floor each leaning against a separate wall for a few minutes now. We've discussed the details of the buttons, the refracted light from the crystals on the chandelier. We've searched our vocabularies for the name of the wood and settled on mahogany. Now, I guess Mabel thinks it's time to move on to topics of greater importance. God, he was cute. Cute, no. Okay, I'm sorry. That sounds patronizing. I just mean those glasses, those sweaters with the elbow patches with real ones that he sewed on himself because the sleeves were through. He was the real deal.

"I know what you're saying," I tell her and "I'm telling you that it isn't right." The edge of my voice is impossible to miss, but I'm not sorry. Every time I think about him, a black pit blooms in my stomach and breathing becomes a struggle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour's 2017 novel, We Are Okay, is widely acclaimed for its raw storytelling and emotional resonance. It receives several notable accolades, including the Michael L. Printz Award. The novel follows a young girl confronting her past, navigating through the process of understanding and healing. For Mark, Nina's writing served as an example of the emotional impact of being open, genuine, and vulnerable.

Mark Oshiro:

This is a scene in which their dynamic of their conversation switches to something so intimate so quickly. It is awkward and you as the reader can feel it's awkward, but yet it's so beautiful to me. I think it also demonstrates this way Nina LaCour has of writing about emotions where I often describe to people We Are Okay is a book where every word is in its exact right place. It is. That's a brief section of that book. It just is a punch in a gut and also a hug, because I see the act of writing through those things as a hug as well, because it is an attempt to put something out in the world and someone else is going to read it and they're not alone suddenly.

That's how I felt reading this book, dealing with the lasting grief of the death of my father. I had had another friend die about six months before this book came out. So, those thoughts were very, very fresh on my mind. I'd like to think that the work that I put out is also very much in conversation with the things that I have read and devoured. I think this one is too.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Mark's debut novel, Anger Is a Gift, came out a year after LaCour's We Are Okay and similarly packed a lot of that emotional gut punch. The story is about a young boy dealing with the traumatic aftermath of the loss of his father to police violence. It delves into heavy themes of racism, identity, and mental health. The story was fiction, but to write it, Mark had to take a deep breath and dive into a past that they had never before been public about.

Mark Oshiro:

I think if anything, now I look back on my fear and I think what I couldn't see at the time before it came out was I was writing from this place of both vulnerability but also authenticity of there are things in this book that I have experienced or gone through or witnessed and I think that's what I tapped into with that book. It's the thing I hear, this book feels so real. It feels so alive in a lot of ways. I don't think I could see that at the time. I was so close to it, both emotionally. When you're editing, when you're just going through a book over and over and over again, it's really hard to see the forest for the trees. But I'm very proud of it and proud of the impact it has had all these years.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Anger Is a Gift earned Mark a Kirkus Book of the Year nod, a Lambda Award, and a lot of devoted fans, one of whom happened to be a familiar name.

Mark Oshiro:

The nice cherry on the top of all of this is that I had this transformation in my own perception of my book and also being able to just let go and be like, "If this book can come out and then the next year wins an award, you're going to be okay, Mark. It's okay. This book is heavy. Yes, it's very personal, it's very intimate, but other people are doing it." It's very much the thing of once you watch someone else do it, you're like, "Oh, okay, I can do this." Then the next year in, I think it was April when I got the email and I get an email from my publicist that was like, "Oh, Nina LaCour is going to do your event in San Francisco." I was like, "What? No, no, no. This should be the other way around."

Oh, she made me cry so hard. But as soon as I showed up at the bookstore, I will not share my details to have forever, but she just said the nicest thing about Anger Is a Gift that just was what a beautiful full circle moment for me. Then I told her once we did the discussion, "By the way, here's my relationship to you and your book. So, getting to have this moment feels very important to me." So this book is deeply important to not just me as a person, but me as an author.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Let me pause here for a second, because I may have given you the impression that Mark just came blasting out of the gate as this writer of fearless self-confession and heartfelt uncompromising candor. Well, the real story is that by 2018, Mark had already been writing publicly for almost a decade, but it wasn't exactly soul bearing novels. In fact, it was the opposite in every way. An irreverent blog where Mark reviewed popular young adult books and TV shows from behind a thick wall of ironic snark. They called it Mark Does Stuff.

Mark Oshiro:

So much of where this Mark Does Stuff universe came from is I missed out on everything. All these popular series, all these popular books, these television shows, I don't know what they are. I didn't grow up with them. So, I was doing this job working for this company called Buzznet. Actually, I mean it started as a joke between my coworkers, because the Twilight books were doing really, really well. I was like, "What? These are not my vampires", but I was a little curious.

So, it was born of this idea of there is something fun about getting into something you don't know that everyone else knows. So, it started as a joke, this little blog where I had a full-time job. I can only read one chapter a day, so I'll write a chapter and then just write a snarky review of it. Then it took over my life for 13 years. I read something like 150 different books.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That are always books or things that everybody else is aware of. So, we're on the inside.

Mark Oshiro:

And that I didn't know what it was.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, but it's also interesting because someone brought this up. I did an event in Portland this summer and someone who had been reading the whole time, both Mark Does Stuff and then now into my fiction, was like, "Do you remember how snarky and witty you were at the beginning and how the series then evolved into actually studying and appreciating these series, what they were?" But they were like, "Have you ever gone back and read your Hunger Games reviews?" I was like, "Oh, I was an asshole." I was just making fun of the YA tropes and stuff like that, but it was in the middle of that series where I started being like, "But this is actually really good."

It might have tropes that are popular and fun to make fun of, but there is some serious commentary happening here. It was something that just clicked in my brain of "Wait, there's another way to do this that isn't just snark." So the project shifted at that point in a lot of ways to be about I want to discover why all of you like this.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, looking like several levels deeper. So, from that shift in the blog over time and then we get to Anger Is a Gift and now Into the Light, your most recent solo novel, your work has become this increasingly earnest and open and nearing autobiographical. We've talked about how these characters like Manny or Cesar from Into the Light mirror some of the more specific aspects of your childhood. I was wondering, is it daunting for you to push your writing in that direction? I guess, does it change the way that you feel about your own story?

Mark Oshiro:

So part of what I feel post writing Into the Light is freedom. It's very basic, but it is a great example of it. I've talked about some very personal, very upsetting things, and I don't cry about it anymore. This is a thing that would prior, I would get very, very upset, understandably very upset about it. It's not that I am dissociating from it now. It's that I'm like, "Oh, I can understand what it was and also understand it from a place of not blaming myself for any of it and thinking that any of this was my fault and not thinking as often Manny does like I'm a burden for telling people about this or I was a burden when I was younger."

So a lot of what I feel is freedom. I feel not entirely, I would say, because we have a new therapist here in Atlanta and we're still working through a lot of this stuff. But I do feel free from a lot of that pain and that trauma, having been able to talk to people in person who have experienced religious trauma, who have experienced trauma around adoption and getting to hear their specific reaction. Those are the people I was thinking of. I didn't know them, but I was thinking of them as I was writing the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For those readers, it's easy to imagine how Mark's books can be, as they described it, a hug that acknowledges their own similar experiences, but of course, there are legions of readers who love Mark's work but haven't lived anything like it. Conversing with them can be less comfortable.

Mark Oshiro:

I think where the practice of vulnerability, where I've had to practice it and learn it is the people who do not relate to anything at all but want to ask very personal questions. So, I go into these situations with empathy, trying to have empathy of why a person is asking this and trying to also see it as a question asked in good faith. Part of it is just hope. You have hope for other people that they're coming to you, like I said, in good faith. They are curious and it's practice.

Vulnerability is practice. It is learning that you can do things and say things that seems scary, but ultimately know that you're safe. So, I try to build that not just into my work as a whole, but when I talk about it, how can I make it feel like this space right now and this difficult thing we're talking about is safe and we're all okay to have a difficult conversation.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Speaking of responses to your work, can you think of any meaningful moments that really stood out that you've had while visiting students?

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah. The first time that happened was I did a school visit outside of Chicago in 2018. This short gruff Latino kid came up after my event and he held up Anger Is a Gift, which is a thick book, even bigger than Into the Light and was like, "Hey, this is the first book I've ever read." I just laughed at him and his friends were doing that thing like jostling him with his shoulders like, "Talk to him." I was like, "Wait, what?" He was like, "No, I don't like books, but this is the first book I've ever read cover to cover."

Immediately, tears welled my eyes and I was like, "Are you serious?" He was like, "Yeah." Then he said, "I didn't know people like us were allowed to write." Of course, I know what that feels like. I remember being that person until Miss Elford, 14 years old, hands me The House on Mango Street. That was for me my permission. That was my book I read that I was like, "Oh, we're allowed to do this."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, that's a great and powerful story. Are there any other, I guess, more recent stories you want to share with us?

Mark Oshiro:

I just got back from a school visit in Cary, North Carolina that was extremely chaotic and beautiful.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Why was it chaotic?

Mark Oshiro:

I've been to the school before. They teach The Insiders to all of their sixth graders.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Really? In Cary, North Carolina?

Mark Oshiro:

In Cary, North Carolina. So, the school visit was in two parts. The first half of the day, I did individual projects with the kids. I had to step out of the room, because I was getting so emotional about it. They found a room on campus that they could turn into a magical closet. So, they were coming in with ideas of "How can we make this room the maximum amount of safe for the maximum amount of people and what happens when people's needs overlap with other people's?" I was just sitting there, I can't believe this is happening. Then so all these kids had never met an author, so they were feral. They were just like, "Oh, my God. Tell me everything. Who's the most famous person you've ever met? How much money do you make?" So I feel very renewed, now finally rested, but very renewed. It's like that reminder of "Oh, this is why I do this."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Into the Light has just been this really big moment, it seems like, in your life, coming to terms with your own story and being more vulnerable than you have been before. I'm sorry to learn that your mom passed away before the book came out. Did you ever reconcile with her or get some form of closure?

Mark Oshiro:

Sort of. What I know about how the first reconciliation came about was when my brother was particularly resentful because my mom didn't go to our graduation, because she didn't want to see me. I'm very proud of this. I was valedictorian.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Hey.

Mark Oshiro:

Through all of that, I still-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That's incredible.

Mark Oshiro:

You know what it was though? It was spite. I got to this point where I was like, "If you're not going to support me, well, then I'm going to do great without you." It was very much a motivating factor, but I know part of why my brother wanted reconciliation is he was also very, very angry with my mom. By the way, deeply supportive throughout all of this, he actually never once was like, "You have to come home. You have to reconcile." He was like, "I get it." I'll use modern language, but he was like, "Girl, live your best life." Very much in this I'm getting to see you be free for the first time ever. So, we did finally have a conversation about a month before my brother and I left for college, and we went to separate universities. I had somewhat of a relationship with her.

It was this thing of always trying and it might feel good, but then she would slip back into a lot of her tendencies. I did have a really good relationship with my father until he passed away in 2006 and had some of my favorite conversations in my whole life with him in the last year before he passed. Some of them where he was like, "I did not stand up enough for you and your siblings against our mother. P.S., she was also doing wild things to me." It was this thing of as an adult being able to understand and then recall what was happening in that house and was like, "Oh, she was abusing him too." That's a thing that you don't necessarily... No, I won't say don't, because some kids can pick up on it, but I don't think I ever-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's not the trope you're used to hearing, so you're not looking for it.

Mark Oshiro:

No, not at all. Well, particularly because of gender and race. My dad was a dark-skinned Japanese Hawaiian man being abused by a white mother, and that is certainly not a trope or something that you see. So, of course, a lot of that stuff went right over my head. So, the piece I made is the level to which she abused myself and my brother and our younger sister was so intense and so relentless and she never apologized for it.

I think my whole career up Into the Light is I am doling parts of myself out, little parts, because I don't want to talk about the big part. Then I talked to a big part and now I'm like, "Oh, I actually really like going just to the little parts where there are little things that I've experienced. There are elements of my next middle grade that are personal about grief." I'm writing a new YA that's a love story-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, you are.

Mark Oshiro:

... that I've never done before. But so much of this book now is just fully made up and it has given me this new burst of creativity.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Your love story is fully made up, you said?

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah. Oh boy. It's very made up. It's extremely made up.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You're like, "Let me be clear."

Mark Oshiro:

In all parallel universes. It's very speculative, but it's dealing with an emotional truth that I dealt with and I'm like, "Well, how do I take this emotional truth and put it over here?" It's given me a joy, a new type of joy. I certainly had joy writing the books that came prior to this, but it's this new joy, because I think there is a fear in a lot of us who have written about very personal vulnerable things that you don't have any ideas after that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, but it sounds like what you're saying is like you actually wrote the big one and now it feels like you have a new lease on being able to do other things, right?

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, absolutely.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Learning to share their story and be vulnerable has shaped Mark's career and changed their life. So, for the reading challenge, Stories of Vulnerability, they want us to explore other stories that feature the same amount of rawness that they bring to their work.

Mark Oshiro:

I was thinking both recent books and a book or two that were deeply influential to me in thinking about writing main characters who are raw, their emotions are on the page. There's no mystery about how they feel about things, but the mystery might be "How do they deal with those feelings? What does it mean to have complicated, messy, harmful, toxic feelings about yourself, about the world, about your circumstances as well?" So I chose a list of all young adult books, and not only all young adult books, but all books by authors of color that deal with vulnerability in different scenarios.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You can find Mark's challenge, Stories of Vulnerability at thereadingculturepod.com, along with reading challenges from all of our past guests, including Sabaa Tahir, Meg Medina, Renée Watson, and many more. Today's Beanstack featured librarian is Cindy Philbeck, teacher librarian at Wando High School in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. She told us about her library's lunchtime strategy that encourages students to come visit and see the space as a place of refuge.

Cindy Philbeck:

What's unique at our school is that the library is not a quiet study zone. It is a loud, lively place during our lunches. We have third block lunches. So, we have an hour and a half every day where maybe a little bit more than an hour and a half, each lunch is about 45 minutes. So, we have a period throughout the day, where all we do is talk with students, allow them to come in and relax, have recreation time, choose books, play games, board games, anything tactile and fun. I mean, they destroy a deck of UNO cards in a minute. They just want to play chess. They want to take a break from their devices most of the time. Now, there are quite a number of students over in the quieter zone where they're studying or they're doing some small group work, but for the most part, lunch is lively.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Mark Oshiro. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey. Currently, I'm reading The Memory Thieves by Dhonielle Clayton and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray. If you've enjoyed today's episode, please show some love and give us a five-star review. It just takes a second and really helps.

To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com, and remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and insights. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josiah Lamberto Egan. Thank you for joining and keep reading.

It's practice. Vulnerability is practice. It is learning that you can do things and say things that seem scary, but ultimately know that you're safe.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In Mark Oshiro's formative years, they were taught to fear the world around them. They were isolated and controlled in all areas, but one, books. When teenage Mark eventually tried to push back against those restrictions, overnight, they found themselves alone and without a home. Mark's writing career has been a journey to accepting this traumatic past, learning to process it, and discovering the value of being open with others. Their novel, Into the Light, serves as a culmination of these discoveries so far.

Mark Oshiro:

I will say writing it was very healing. To be able to name it and say it out loud and to devise a character's journey knowing that there's light at the end of the tunnel too, it did make writing about it a lot easier than I expected when I started the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Mark is a Hugo-nominated writer, best known for Anger Is a Gift, Each of Us a Desert, the latest installment in the Percy Jackson universe, The Sun and The Star, and of course, Into the Light. They also created The Mark Does Stuff universe, which for 13 years featured blogs reviewing popular books and TV series sometimes with a little less sensitivity than Mark's more recent writing.

Mark Oshiro:

That was a moment where I was like, "Okay, Mark, if you can't just make a "My parents are dead" joke to a random stranger..."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

In this episode, Mark shares their life story and reflects on the refuge that books and libraries offered them as a youth from an abusive household. They discuss how lowering their emotional defenses led them to discover the healing power of vulnerability, and we'll also learn the franchise they ripped off as a kid that kicked off their love of writing. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators about ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities.

We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways at The Reading Culture Pod, and please also subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

I know that you were adopted and that has played a really important role. So, you want to talk about your early childhood and some of your early experiences?

Mark Oshiro:

I have an identical twin brother who's based in Maryland, who is an educator. It's very interesting because we've almost switched places, because growing up, everyone was like, "Mark will be the one with five degrees and is a teacher, and Mike will be the one traveling the world with a bunch of tattoos and is a big weirdo." Somewhere in our 20s, we switched places. What's interesting about talking about being adopted as well is unfortunately, for a lot of adopted kids, we can't really piece together our childhoods. We don't have a concrete history. I know we were in foster care for at least a year, possibly two years, but we were told a story about how we were adopted and how we came into our family.

It wasn't until about two years ago that we found out that most of it wasn't true and that we were told a story that made it seem very much like our parents and in particular our mom were saviors, that they rescued us from this very dangerous, heightened situation and it just wasn't true. We've since gotten in contact with our biological mom's sister who has provided us with documents. For example, I know what my name was before I was adopted. It was Kevin. When you're raised with a story, you believe it wholeheartedly and you tell other people that story. Then it wasn't until I got in my 20s and 30s that my brother and I started not only questioning it, but other people in our life, particularly people who were social workers, people who worked in foster care.

We're like, "That doesn't make sense." Something is missing, but we were like, "Well, we don't know. We can't really provide it to you. This is what we were told."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was the story that she told you?

Mark Oshiro:

We had a drug addicted mother who was going to give us away to the streets or something, which-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The typical... Right, yeah.

Mark Oshiro:

That was adults. That's so absurd, but as a kid, you're like, "Oh, my God. The streets. What are the streets? Oh, my God. I don't want to go there." It wasn't someone she was related to, but it was like a friend of a family member who she heard through the grapevine. Very much like some of the characters in Into the Light, God told her to go save those children. So, she went through this long, lengthy, protracted adoption process and adopted us and saved us. Then the other half of it being we spent most of our childhood believing someone was trying to take us back. So, we were not allowed to have friends over to the house. No one was allowed to know where we lived. We were not allowed to do afterschool events until we were about 15 or 16 years old.

Then if we did well, she would pull us out of them, because she didn't want attention on the family. That was what the environment I was raised in, this white saviorism mixed with this very overprotective behavior, also mixed in with a very, very nationalistic sense of Christian identity. We had to mold ourselves into essentially the perfect white people, even though we weren't. What an identity crisis to be put in as a child. I remember being very young, being like, "Some of this is bullshit. This doesn't make sense. I don't understand it, but I don't have the words."

So I often think when I'm writing, how can I give words to someone who doesn't know how to describe their experience? It's why Into the Light is I feel like it's the most specific book I've ever written. I am very much speaking to that younger version of myself and saying, "You're going through this thing that doesn't make sense, and it's because it's never going to make sense."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's so odd to be a kid having to come to that realization to see things for what they are when you don't really have a way to see them for what they are. To have to come to that on your own over time, that seems hard.

Mark Oshiro:

But I like that you put it that way too, because it meant that there wasn't much magic in terms of the childhood. I certainly had positive memories, and particularly of my siblings. My twin brother and I are still best friends to this day, but it's more that when I hear other people talk about their childhoods and that idea of blissful ignorance, I got to live in a time where I didn't know there were things wrong with the world and I just got to be a kid. I'm sitting there like I don't know what that's like, because at a very, very young age, I was constantly told how the rest of the world was wrong and how many evil things were out there both in terms of society. Brown, Black people are evil, the streets, right? Yeah. That's a story of this external thing that's coming to get you.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What were your relationships with teachers and do you think that they-

Mark Oshiro:

Oh, my God.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did they ever wonder what was going on?

Mark Oshiro:

They all knew it was not a good environment at home and they could tell. Now, as an adult, I'm like, "Oh, of course, they could tell. Of course, they were cognizant of not only some of the things I might be saying in class, but I was a very shy kid." My fifth grade teacher reached out to me probably two or three years ago and was like, "You were the most frightened little boy I've ever seen in my life." I remember her telling me that the only time I lit up was when I was asked to read in class. I think that's what the teachers certainly in elementary school picked up on was here was the one thing Mark was thrilled about and was excited about and would open up.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I've heard that your mom was very encouraging of you reading no matter what it was. You said that she was a Christian nationalist, or how would you describe her?

Mark Oshiro:

So my mom was virulently anti-anyone outside of the United States. So, at home, we were told the United States is the best country and it's because we all believe in the right Jesus. Then it became well, it's only our city. Then it became well, it's only our community. By the time we're like 10 and 11, it's only our house. Nowhere else is safe. That being said, and this is a thing, my brother and I and I have a younger sister as well, who incidentally also adopted, also the same biological mom, but she has a different biological dad. We were surveilled as kids. Anything you brought into the house, it was let me make sure that that's okay with the exception of books and the X-Files and the Twilight Zone. My mom loved those shows.

So, a joke I make sometimes when I'm doing school visits is like I live this heavily regimented life, but I was allowed to watch a TV show that had literal demons on it. In my mom's mind, my interest in English and in reading and generally doing well in school would save me from the streets, would save me from this life of being destitute, addicted to drugs, in a gang, any of those things. So, while she may not have actually had a connection with me, like a deep emotional connection with me as a child, that part she was very supportive of.

She loved that I read. She loved that I was always reading. She would encourage me. I mean, we had the World Book Encyclopedias. So, sometimes she'd be like, "What letter are you going to read this month?" It was probably the only thing I ever really truly bonded with her over.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did she in surveil what books you were reading at home or did it matter? Could you take them out from your school library?

Mark Oshiro:

No.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You could read anything you wanted.

Mark Oshiro:

No, if they were in the school library for some reason, it was okay, but not music. Music, television shows, movies, no, but there was something about the written word. I mean, to give you an example, I have a much, much older sister who moved out of the house years and years before I discovered this, but I think when we were like four or five. She left behind a box of her books, and I'm eight years old sitting on the couch reading Stephen King's IT.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nuh-uh.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, that was the first adult book I ever read. I didn't truly understand it, but it gave me my love of horror and all things spooky. So, this is a podcast, so they won't be able to see this, but I do keep these on my desk. Literally, I'm holding up a laminated book I wrote. This was 1994, so it was 10 years old. It's Mark Oshiro's Goosebumps. We can also laugh. It's called Stay Out of the Closet. I love that message for myself, but I wrote 13 or 14 of these.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow.

Mark Oshiro:

But I only wrote the one and then I have another one here that my teacher was like, "You should make your own series." So I made this series. I'm holding up another one. It's called Terrifying Tales and I wrote 13 of these.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So despite the intense regulation on the rest of their life, books served as Mark's sole escape, the only place where they were able to navigate freely. However, that sole refuge would slowly slip away as they grew older. At the same time, Mark began to realize that their mother's painting of the outside world just didn't match what Mark was seeing.

Mark Oshiro:

I think part of the consciousness came from living in Southern California in a minority, majority city. I grew up in Riverside, California. I would say 60 to 70% of the kids around me were Central American. They were Mexican, El Salvadorian, Guatemalan. So, I'm finally around people who have black hair, brown skin. My brother and I are able to start speaking Spanish even though we've never learned or at least we thought we'd never learned a word of it. So, there is that consciousness that comes with, "Why is this so easy? Why do I look like these people? But I'm being told they're bad, but I'm around them every single day and I love my friends. I love who I'm around. It just doesn't make sense."

So it's that the awareness came from the contradiction of here's what I'm being told, but anytime I'm away from the house, I'm experiencing something different. So, there's this friction that's happening that forces you even at that age to start being aware, you have to start paying attention.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. How did that play out as you got older?

Mark Oshiro:

I had a very public traumatizing moment in the middle of high school, about a month into my junior year. For context for your listeners, up until that point, my first two years of high school, this idea that my mom was slowly closing what was allowed and what my brother and I were allowed to do had gotten so small that she used to go to my school and interrupt me in classes-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow.

Mark Oshiro:

... to punish me for things that I had done at home.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wait, that's so humiliating for a kid. So, she would come like when to do what? To come to your class?

Mark Oshiro:

She became known on campus and then to start denying her access because she would just walk onto campus. The first memory that came to mind was one morning she came to class to yell at me. She yelled at me for not putting clothes away correctly. Obviously, all of this is an overreaction, but a thing that I've processed with therapists is that it never was about actually doing anything wrong. I believe that she started to realize she was losing her grip on the two of us and is freaking out. So, I had this teacher who I'm still friends with on Facebook today, who I will say right now, Ms. Alford, if you're listening to this, she saved my life. She latched onto me and recognized something into me when I was a freshman. She was my freshman year English teacher.

I literally would not be able to sit here talking to you like this if it wasn't for her. She taught me public speaking. I became much more confident in myself. My mom became horribly threatened by this relationship. She very publicly pulled me out of mock trial and yelled at my teacher in front of all of my peers, because we were two minutes late during a practice once. We went over two minutes. She got so mad at Ms. Alford, she spread a rumor that Ms. Alford was sleeping with me. I give you this context to understand I'm 16 years old.

I have no friends outside of school. I'm not allowed to go anywhere. I have my first job, so I'm allowed to go to school, cross-country practice, and I have this job at a grocery store where my mom would sit in the parking lot and surveil me and watch me. If I talked to anyone, she would later ask, "Who was that? Tell me everything you said."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Wow. She was physically observing you.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, it came to a head, because my brother was not as surveilled but pretty heavily surveilled as I was. We devised this whole system where we... I mean, this is a very teenage thing to do. We told our mom that cross-country practice ended at 5:00 every day, and it ended at 4:00. For an extra hour, we would go to our friend's houses and just hang out with someone.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Be normal, just get to do things that kids do.

Mark Oshiro:

She caught us. I won't go into details, because it was very violent, but she abused the two of us physically, but she focused almost all of it on me. So, it was this thing where I was trying to piece together, "Why am I being the target of a lot of this?" It wasn't until she said something to me that was incredibly homophobic, and then I was like, "Oh, that's why." That day that we have this huge fight, she tells me to leave and never come back. I don't want to ever see you again. So, that was the day. If you heard it from my mom, she would say, I ran away from home, but I always believed I was kicked out because she told me to leave. I spent the remainder of high school estranged from my family.

My mom did nothing to bring me home. She never wanted me back around. It took two and a half years for me to be able to even speak to her. I had to survive high school. Either I was couch-surfing with friends. There were a few educators who put their whole careers on the line to be like, "Do you need somewhere to sleep? Knowing that this is unethical, but you don't have any other choice, so I'd rather do the thing that is nice and can help you and potentially risk my career."

They knew and I knew too, this is a big deal, but I think I lived in 20 different places by the time I graduated high school and sometimes on the street. There was a particular park that if I didn't have anywhere to go, it had this jungle gym thing that if you set up underneath, it would block any potential rain. Now since you've read Into the Light, that's where that particular heartbreak comes from and it isn't fictional. I knew what it felt like.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

If you've read Into the Light and I highly recommend it, you'll have noticed a lot of similarities with Mark's personal narrative. The book follows a young boy, Manny, who is cast out by his family and must navigate life in the road on his own. Little pieces of the novel are so physically and emotionally specific that they stayed with me long after reading.

For instance, there's this one heartbreaking scene where Manny, living with another family, painstakingly puts a towel under the door while he showers to prevent light from escaping and potentially disturbing others in the motel room. He's consumed with anxiety that the slightest mistake or imposition will get him rejected from yet another home. I asked Mark about this, and they told us it does indeed take direct inspiration from old habits.

Mark Oshiro:

That's all my routines in the places that I live thinking the little details, don't leave body hairs behind. Something just so simple as that because it's like you don't want anyone to remember that you're there and it's a thing you learn as a survival technique of. This is a very crass way of thinking about it, and I liked getting to write Manny thinking about it in that very direct way too. But once you become annoying to someone, your time in that place is up. It's true. I knew every time when I'd overstayed, I could feel it. I could sense it in the air or I'd hear a complaint about "Hey, could you not do this around the house?" I'm like, "That's strike one. I understood, I don't live here. I'm not your child." There's another character he meets on the road, Cesar, the rules.

A lot of that came from my experience of learning how to navigate houselessness as a teenager. I know now even saying that, that is sad. It is a really sad thing to have to experience at that age, but I will say writing it was very healing. To be able to name it and say it out loud and to devise a character's journey knowing that there's light at the end of the tunnel too, it did make writing about it a lot easier than I expected when I started the book, because I certainly dreaded writing certain passages or certain scenes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, my gosh. Yes. I mean, the way you wrote so many of these emotions is really raw and touching, and it just must've been such an unimaginably difficult time for you. I did wonder if you still were able to read and find that respite despite all the turmoil in your life at that time.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, I was still constantly reading as a person who was almost at the time, the library was my best friend. I associate that place with comfort, with warmth food. The librarian often had snacks behind the counter. I would just sit and just pull a book off a shelf and read, or sometimes I would go up to the librarian and just be like... You know that ridiculous thing like I want a book that is going to give me nightmares for 400 years. She's like, "I have the perfect one."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I have the one.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, I have the one.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So the library was your spot.

Mark Oshiro:

Oh, absolutely, absolutely. I would say my middle school library, my high school library, and the public library, I spent a great deal of time in. So, oftentimes that's where I would have to do homework, because I didn't have somewhere to go. I loved that feeling of wandering down the shelf and just seeing a spine that maybe looked a little weird and the color was brighter than the others and pulling it out, reading the little synopsis on the back, and being like, "I don't know what any of this is." Okay. It just was always so exciting to me. It was also books were my window to the outside world. When you live in such an insular, repressed environment, that was my chance to see what is actually going on with other people and other families.

"I've been thinking about your grandpa a lot," Mabel says. We've been sitting on the elevator floor each leaning against a separate wall for a few minutes now. We've discussed the details of the buttons, the refracted light from the crystals on the chandelier. We've searched our vocabularies for the name of the wood and settled on mahogany. Now, I guess Mabel thinks it's time to move on to topics of greater importance. God, he was cute. Cute, no. Okay, I'm sorry. That sounds patronizing. I just mean those glasses, those sweaters with the elbow patches with real ones that he sewed on himself because the sleeves were through. He was the real deal.

"I know what you're saying," I tell her and "I'm telling you that it isn't right." The edge of my voice is impossible to miss, but I'm not sorry. Every time I think about him, a black pit blooms in my stomach and breathing becomes a struggle.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Nina LaCour's 2017 novel, We Are Okay, is widely acclaimed for its raw storytelling and emotional resonance. It receives several notable accolades, including the Michael L. Printz Award. The novel follows a young girl confronting her past, navigating through the process of understanding and healing. For Mark, Nina's writing served as an example of the emotional impact of being open, genuine, and vulnerable.

Mark Oshiro:

This is a scene in which their dynamic of their conversation switches to something so intimate so quickly. It is awkward and you as the reader can feel it's awkward, but yet it's so beautiful to me. I think it also demonstrates this way Nina LaCour has of writing about emotions where I often describe to people We Are Okay is a book where every word is in its exact right place. It is. That's a brief section of that book. It just is a punch in a gut and also a hug, because I see the act of writing through those things as a hug as well, because it is an attempt to put something out in the world and someone else is going to read it and they're not alone suddenly.

That's how I felt reading this book, dealing with the lasting grief of the death of my father. I had had another friend die about six months before this book came out. So, those thoughts were very, very fresh on my mind. I'd like to think that the work that I put out is also very much in conversation with the things that I have read and devoured. I think this one is too.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Mark's debut novel, Anger Is a Gift, came out a year after LaCour's We Are Okay and similarly packed a lot of that emotional gut punch. The story is about a young boy dealing with the traumatic aftermath of the loss of his father to police violence. It delves into heavy themes of racism, identity, and mental health. The story was fiction, but to write it, Mark had to take a deep breath and dive into a past that they had never before been public about.

Mark Oshiro:

I think if anything, now I look back on my fear and I think what I couldn't see at the time before it came out was I was writing from this place of both vulnerability but also authenticity of there are things in this book that I have experienced or gone through or witnessed and I think that's what I tapped into with that book. It's the thing I hear, this book feels so real. It feels so alive in a lot of ways. I don't think I could see that at the time. I was so close to it, both emotionally. When you're editing, when you're just going through a book over and over and over again, it's really hard to see the forest for the trees. But I'm very proud of it and proud of the impact it has had all these years.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Anger Is a Gift earned Mark a Kirkus Book of the Year nod, a Lambda Award, and a lot of devoted fans, one of whom happened to be a familiar name.

Mark Oshiro:

The nice cherry on the top of all of this is that I had this transformation in my own perception of my book and also being able to just let go and be like, "If this book can come out and then the next year wins an award, you're going to be okay, Mark. It's okay. This book is heavy. Yes, it's very personal, it's very intimate, but other people are doing it." It's very much the thing of once you watch someone else do it, you're like, "Oh, okay, I can do this." Then the next year in, I think it was April when I got the email and I get an email from my publicist that was like, "Oh, Nina LaCour is going to do your event in San Francisco." I was like, "What? No, no, no. This should be the other way around."

Oh, she made me cry so hard. But as soon as I showed up at the bookstore, I will not share my details to have forever, but she just said the nicest thing about Anger Is a Gift that just was what a beautiful full circle moment for me. Then I told her once we did the discussion, "By the way, here's my relationship to you and your book. So, getting to have this moment feels very important to me." So this book is deeply important to not just me as a person, but me as an author.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Let me pause here for a second, because I may have given you the impression that Mark just came blasting out of the gate as this writer of fearless self-confession and heartfelt uncompromising candor. Well, the real story is that by 2018, Mark had already been writing publicly for almost a decade, but it wasn't exactly soul bearing novels. In fact, it was the opposite in every way. An irreverent blog where Mark reviewed popular young adult books and TV shows from behind a thick wall of ironic snark. They called it Mark Does Stuff.

Mark Oshiro:

So much of where this Mark Does Stuff universe came from is I missed out on everything. All these popular series, all these popular books, these television shows, I don't know what they are. I didn't grow up with them. So, I was doing this job working for this company called Buzznet. Actually, I mean it started as a joke between my coworkers, because the Twilight books were doing really, really well. I was like, "What? These are not my vampires", but I was a little curious.

So, it was born of this idea of there is something fun about getting into something you don't know that everyone else knows. So, it started as a joke, this little blog where I had a full-time job. I can only read one chapter a day, so I'll write a chapter and then just write a snarky review of it. Then it took over my life for 13 years. I read something like 150 different books.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That are always books or things that everybody else is aware of. So, we're on the inside.

Mark Oshiro:

And that I didn't know what it was.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah, but it's also interesting because someone brought this up. I did an event in Portland this summer and someone who had been reading the whole time, both Mark Does Stuff and then now into my fiction, was like, "Do you remember how snarky and witty you were at the beginning and how the series then evolved into actually studying and appreciating these series, what they were?" But they were like, "Have you ever gone back and read your Hunger Games reviews?" I was like, "Oh, I was an asshole." I was just making fun of the YA tropes and stuff like that, but it was in the middle of that series where I started being like, "But this is actually really good."

It might have tropes that are popular and fun to make fun of, but there is some serious commentary happening here. It was something that just clicked in my brain of "Wait, there's another way to do this that isn't just snark." So the project shifted at that point in a lot of ways to be about I want to discover why all of you like this.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, looking like several levels deeper. So, from that shift in the blog over time and then we get to Anger Is a Gift and now Into the Light, your most recent solo novel, your work has become this increasingly earnest and open and nearing autobiographical. We've talked about how these characters like Manny or Cesar from Into the Light mirror some of the more specific aspects of your childhood. I was wondering, is it daunting for you to push your writing in that direction? I guess, does it change the way that you feel about your own story?

Mark Oshiro:

So part of what I feel post writing Into the Light is freedom. It's very basic, but it is a great example of it. I've talked about some very personal, very upsetting things, and I don't cry about it anymore. This is a thing that would prior, I would get very, very upset, understandably very upset about it. It's not that I am dissociating from it now. It's that I'm like, "Oh, I can understand what it was and also understand it from a place of not blaming myself for any of it and thinking that any of this was my fault and not thinking as often Manny does like I'm a burden for telling people about this or I was a burden when I was younger."

So a lot of what I feel is freedom. I feel not entirely, I would say, because we have a new therapist here in Atlanta and we're still working through a lot of this stuff. But I do feel free from a lot of that pain and that trauma, having been able to talk to people in person who have experienced religious trauma, who have experienced trauma around adoption and getting to hear their specific reaction. Those are the people I was thinking of. I didn't know them, but I was thinking of them as I was writing the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

For those readers, it's easy to imagine how Mark's books can be, as they described it, a hug that acknowledges their own similar experiences, but of course, there are legions of readers who love Mark's work but haven't lived anything like it. Conversing with them can be less comfortable.

Mark Oshiro:

I think where the practice of vulnerability, where I've had to practice it and learn it is the people who do not relate to anything at all but want to ask very personal questions. So, I go into these situations with empathy, trying to have empathy of why a person is asking this and trying to also see it as a question asked in good faith. Part of it is just hope. You have hope for other people that they're coming to you, like I said, in good faith. They are curious and it's practice.

Vulnerability is practice. It is learning that you can do things and say things that seems scary, but ultimately know that you're safe. So, I try to build that not just into my work as a whole, but when I talk about it, how can I make it feel like this space right now and this difficult thing we're talking about is safe and we're all okay to have a difficult conversation.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Speaking of responses to your work, can you think of any meaningful moments that really stood out that you've had while visiting students?

Mark Oshiro:

Yeah. The first time that happened was I did a school visit outside of Chicago in 2018. This short gruff Latino kid came up after my event and he held up Anger Is a Gift, which is a thick book, even bigger than Into the Light and was like, "Hey, this is the first book I've ever read." I just laughed at him and his friends were doing that thing like jostling him with his shoulders like, "Talk to him." I was like, "Wait, what?" He was like, "No, I don't like books, but this is the first book I've ever read cover to cover."

Immediately, tears welled my eyes and I was like, "Are you serious?" He was like, "Yeah." Then he said, "I didn't know people like us were allowed to write." Of course, I know what that feels like. I remember being that person until Miss Elford, 14 years old, hands me The House on Mango Street. That was for me my permission. That was my book I read that I was like, "Oh, we're allowed to do this."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, that's a great and powerful story. Are there any other, I guess, more recent stories you want to share with us?

Mark Oshiro:

I just got back from a school visit in Cary, North Carolina that was extremely chaotic and beautiful.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Why was it chaotic?

Mark Oshiro:

I've been to the school before. They teach The Insiders to all of their sixth graders.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Really? In Cary, North Carolina?

Mark Oshiro: