About this episode

Hena Khan didn’t believe her perspective mattered. As a Pakistani-American Muslim, she grew up not seeing her or her family reflected in the media she was consuming. As any kid might do, she concluded that it was simply because her experience was not important, a realization that became clearer in hindsight. Recalling her childhood writing, she discovered she had unintentionally whitewashed her homemade family newspaper.

"There's these universal truths [...] specific details, but universal feelings and universal experiences that people hopefully can relate to. And that's what I go for in all of my books. Common humanity.” - Hena Khan

Building confidence in her perspective was a gradual process, that extended into adulthood. Initially lacking self-assurance, she began writing while toning down her cultural identity to conform to perceived publisher expectations. Over time, her confidence grew, and today, she is recognized for authentically portraying stories rooted in her culture and religion.

Reflecting on her own reading experiences, Hena values shared human experiences that transcend cultural backgrounds. She aims to demonstrate that these relatable moments exist in stories featuring non-white characters and diverse cultures.

Renowned for works such as "Amina's Voice," its sequel "Amina's Song," the series "Zara's Rules", and "More to the Story," Hena Khan shares her journey of grappling with invisibility as a young reader and the evolution of her faith in herself and her unique perspective. She also recounts the unexpected connection to a book about Christian white sisters in the 1800s in her unconscious quest for stories reflecting her Muslim immigrant family.

***

Connect with Jordan and The Reading Culture @thereadingculturepod and subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter.

***

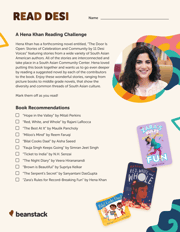

For Hena’s reading challenge, "Read Desi" she wants us to celebrate South Asian American writers. You can find her list and all past reading challenges at thereadingculturepod.com.

Today’s episode’s Beanstack Featured Librarian is Alli Buffington, an elementary librarian in the Santa Rosa County District Schools. She shares about how she makes her school library space one that her students love.

Contents

- Chapter 1 - “Religious Holiday”

- Chapter 2 - Gogol Search

- Chapter 3 - Little Women (and the Khanicles)

- Chapter 4 - Three Cheers From Andrea

- Chapter 5 - Just Living

- Chapter 6 - Common Humanity

- Chapter 7 - Curious About Curious George

- Chapter 8 - The Door is Open

- Chapter 9 - Read Desi

- Chapter 10 - Beanstack Featured Librarian

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

- The Reading Culture

- The Reading Culture Newsletter Signup

- Hena Khan

- Little Women by Louisa May Alcott | Goodreads

- Hena Khan's More to the Story is a Love Letter to Little Women | School Library Journal

- Alli Buffington's Library (this week’s featured librarian)

- The Reading Culture on Instagram (for giveaways and bonus content)

- Beanstack resources to build your community’s reading culture

View Transcript

Hide Transcript

Hena Khan:

And this was something that was very eyeopening to me in terms of realizing the power of representation is that I very much whitewashed my own family newspaper.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Kids absorb a lot. They're kind of famous for it. We've all talked about the little sponges soaking up language and facts about dinosaurs and occasionally social graces. But some of the messages kids absorb are too subtle for them to label and when they're harmful, those can be the hardest to root out. Hena Khan grew up feeling that her heritage and her immigrant family's experience simply weren't important. That the things that made her different from her white suburban peers were better left, well, ignored. And she would internalize that message for years to come. But then in a poetic moment, she opened a book to read and saw her own mother reflected in its pages and she realized what she'd been missing out on. Today, she's a prolific author who has made it her mission to showcase families like her own, both in their differences and in their commonalities.

Hena Khan:

Hopefully anybody can get to know a Pakistani American family, maybe witness some Muslim traditions, but yet feel included too, the way I did in all the books I read as a kid.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Hena is a Pakistani American writer known for the groundbreaking and award-winning Amina's Voice, as well as its sequel Amina's Song. Her titles also include the Zara's Rules series, More To The Story and the beloved picture book, Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns: A Muslim Book of Colors, among many more. In this episode, she'll tell us about the sense of invisibility that she felt as a young reader, the long journey to having faith in herself and her perspective, and she'll also explain how in her unconscious search for books with Muslim immigrant families like her own, she somehow latched onto a book about Christian white sisters in the 1800s. You probably already know the one.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture. A show where we speak with authors and illustrators about the ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways at The Reading Culture Pod, and you can also subscribe to my newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter. All right, on to the show.

Why don't we talk a little bit just about your early childhood and what life was like in Rockville?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I grew up the child of immigrants from Pakistan. My father was one of the very early Pakistanis who moved here, so he came in 1959 and then went back and married my mom. And I was born and raised here in Maryland and grew up in the same neighborhood, the same house for my entire childhood and young adulthood. It's where my mother still lives now. So I used to walk to my local elementary school. And it was a really lovely neighborhood because we had a lot of diverse neighbors. And in fact, my new chapter book series, early middle grade series, Zara's Rules, is based a lot on my neighborhood. But I went to my local public school and I had a pretty uneventful childhood just balancing the normal challenges of being raised by immigrants and trying to figure out where I fit in and having the home life versus school life and private life versus public life.

But now people ask me and kids ask me a lot of times when I do school visits, if I was bullied as a child or what it was like for me growing up. And I tell them all the time that I didn't thankfully feel bullied or unwelcome in any way, but I think what I did experience was feeling a bit invisible. And not only because of books, because I didn't realize I wasn't in books until much later. But I think people just didn't know anything about where my family was from. If I mentioned Pakistan, people, teachers, administrators, kids, everybody was like, "Where's that?" A lot of times they hadn't heard the word Muslim, didn't know what that referred to when I was missing school because of the Eid holiday my parents would sign ... I would write a note actually and make my parents sign it. And I wouldn't even call it Eid because I just assumed nobody knew what that was. So I would just say, please excuse Hena for her religious holiday. That's what I referred to it as.

And I so desperately wanted to fit in, but then at the same time had this other side of me that I really didn't feel was very understood. And at the same time I was consuming the same media, TV, entertainment as everyone else. I was very familiar with Christmas and Hanukkah and all the other traditions and could carol like anybody. I would go caroling with my friends in the neighborhood. There was this sense of I tend to participate in and understand other people's traditions and experience, but nobody really knows mine.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. But you said you felt invisible is the word that you used. And how did that come out?

Hena Khan:

It wasn't like today where you see kids really proud of their heritage or encouraged to be. Maybe they still aren't actually. I know some kids probably aren't. But it's multicultural day or bring your culture to school day or whatever. That type of thing just didn't happen then. And it wasn't so much that I felt like people were being dismissive as much as they just didn't even know what to ask and didn't seem curious, and then I just didn't feel like I needed to share that part of who I was. I don't think I spent a lot of time thinking about it and I didn't really have the vocabulary. Now I look at the words that kids use and even things like culture. I don't think I even used the word culture as a kid. And certainly not words like identity or diversity or all of the terminology we have now to define ourselves. I wouldn't have even called myself a Pakistani American. The hyphenated identity wasn't a thing when I was growing up, so I was just different is what I felt.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And were you a big reader when you were growing up?

Hena Khan:

Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was your reading life like?

Hena Khan:

It was very much imposed on me by my mother in a good way where she was a big proponent of reading. She would take us to the public library every few weeks with bags from the food store and we would fill them up and bring them home. Especially in the summertime, that was what we did. There were no summer camps or activities.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The library was your summer camp.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. It really was. And I'm so grateful for that because I became a big reader. And I think for me especially being this awkward, shy, self-conscious kid, to be able to immerse myself in books, of course just for fun and escape and companionship, but also just to learn about other families and how they functioned apart from what I was seeing on TV.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember some of the books that you were drawn to when you were younger?

Hena Khan:

I loved Beverly Cleary and she's still my literary hero. I read and reread the Ramona Quimby books and all of her stuff and probably checked those out the most when I was little. But I was a really wide reader. I read everything from fantasy to little mysteries. I loved realistic fiction. That was probably what I reread the most, but I don't remember being as picky as I became as I grew older. And I never actually stopped reading a book. If I didn't like it midway I just plowed through it and finished it because I felt like I couldn't not finish it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Well, you mentioned that you didn't notice until later that you were not in all the books that you were reading. Do you remember at the point at which you had a moment of recognition that you weren't seeing your own experience in pages?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I do. It was college. I was at the University of Maryland. I was an undergrad. And I was taking a lot of English classes and I remember taking a African-American literature class and I loved it. And then I took a Caribbean literature class. And at that time there was no South Asian literature class offered. But as I started reading some of these other books, I started looking and I found some South Asian women writers. And I remember being so surprised and pleased in a good way to see things that were familiar to me like a sari and a mango and the language and the culture, but it still wasn't mine. I felt it was set in India for the most part.

So that's when I became aware of the fact that ... I was searching and I read a whole bunch and I liked them to a certain extent, but I didn't love them until I read ... I think it was The Namesake. That was the first time I felt seen. And it wasn't even so much that I felt ... Because it's about a Bangladeshi American multi-generational family, and I definitely identified with the child, Googol, the boy, but what I really saw was my mother. And the opening chapters of the book are about the parents and the mother as a new bride coming to America and sitting in the little apartment trying to find spices to cook with and the intense loneliness that she felt and that just mirrored exactly what my mother used to describe her life like when she first came to the DC area and was living in an apartment in Silver Spring when my dad would go to work. It was that shock of recognition. I was like, this is my mother. My mother is in a book, and that was so powerful to see and that just made me so hungry for more.

"Jo scribbled away until the last page was filled when she signed her name with a flourish and threw down her pen exclaiming, 'There. I've done my best. If this won't suit, I shall have to wait until I can do better.' Lying back on the sofa, she read the manuscript carefully through making dashes here and there and putting in many exclamation points, which looked like little balloons. Then she tied it up with a smart ribbon and sat a minute looking at it with a sober wistful expression, which plainly showed how earnest her work had been. Jo's desk up here was an old tin kitchen, which hung against the wall in it. She kept her papers and a few books safely shut away from Scrabble, who likewise being of literary turn was fond of making a circulating library of such books as were left in his way by eating the leaves. From this tin receptacle, Jo produced another manuscript and putting both in her pocket, crept quietly downstairs, leaving her friends to nibble her pens and taste her ink. She put on her hat and jacket as noiselessly as possible and going to the back entry window, got up on top of the roof of a little porch, swung herself down to the grassy bank and took a roundabout way to the road. Once there, she composed herself, hailed a passing omnibus and rolled away to town looking very merry and mysterious."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Louisa May Alcott's Little Women was published in 1868, but to this day, the strong characters still feel just as palpable through the pages. In this passage, Jo is just about to submit her first article draft to be published in the paper. In the following scene she struggles with building up the nerve to go inside and hand over her work. It was the authenticity and rawness of the emotions and dialogue between Jo and Laurie that inspired Hena to write her book, More To The Story, which follows four young sisters in a Muslim American family in Georgia.

Hena Khan:

I just wanted to pull from my memories of what were the parts that spoke the most to me and the themes that I wanted to infiltrate my book, but I didn't want it to feel like a straight retelling. I wanted a fresh narrative, but with all the things I loved, like the relationship between Jo and Laurie. I wanted my friendship between my characters to feel as sincere and believable and then certain themes that maybe aren't significant to other fans of the book. For me, Jo's anger was something I focus on.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Despite being about a white Christian family in the late 1800s, Little Women became a favorite read and a book where Hena saw her own identity unexpectedly reflected.

Hena Khan:

Martin Luther King Library invited me to speak at an award ceremony for letters and literature, which is, I think it's a national contest where students write to authors living or dead who had an impact on them. And so I was reading the finalists for the competition and they were really moving letters and I was like, "Okay, what am I going to talk about during my comments?" So I thought about who I would've written to if I was in high school and what I would say, and I thought of Little Women. I thought of Louisa May Alcott and why this book resonated so deeply. And I realized that this is where I saw myself probably more than anywhere else in the books I was reading, because even though it was written 150 years ago, a lot of what was in here felt very familiar and comforting to me.

Things like the strict gender norms were recognizable to me. The respect for parents. That was something that always threw me as a teen, especially as a little kid, but even more as a teen, was watching teen shows and seeing the way kids could sass their parents and talk back and I hate you. That was unheard of. I couldn't even talk back, let alone say a bad word or express dislike for my parents. The respect for parents was so profound in this book. Even some of ... My parents had an arranged marriage and the marriage proposals and the expectations around dating and all of that was very familiar. And so it hit me later, I said, for someone probably hungry for representation, this was as close as I got for a while.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And then, well, I'm guessing ... I don't know. Did you identify with Jo?

Hena Khan:

Totally. I didn't realize that the book was not Jo's book. I knew it, that there were chapters told from the other sisters' perspectives, but I just got through those to get back to Jo's story. They felt like filler stories to me. So I was like, "Doesn't everyone identify with Jo? Are there really people who identify with Amy?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. No. Right. Okay. No.

Hena Khan:

But there must be. Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Of course. But interesting. Yeah. So there's both the recognition of the norms, but also identifying them as a young person. Questioning them.

Hena Khan:

Absolutely. Yeah. And I love the fact that she pushed back and felt like she was more. And the fact that she was a writer. I was a little writer too. And I actually wrote a family newspaper.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, like Jo.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And I didn't realize it until much later that, oh, that must be where I got the idea from. I don't remember getting the idea, I just remember doing it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember what your family newspaper was called?

Hena Khan:

Oh yes. The Khanicles.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

No. Do you have any editions of it still?

Hena Khan:

I do. Yeah. Actually there's a few lying around. I took screenshots of them. We found them in a box. I used to save my writings and they're on lined notebook paper that's yellowed with age written in my print.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So good.

Hena Khan:

And if you read it, other than the names, there was nothing that made my family different from the March family or the Quimby family or any of the other families I was reading about. I had a section devoted to food, but I didn't talk about Pakistani dishes that my mother was cooking every day. I just spoke about food in a very general ... Like oh, mom's having a dinner party and she's cooking, and I didn't mention anything about being a Muslim, about our traditions.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Although it was like this major part of your life.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. Yeah. I had an advice column. People could write it. I wrote in and then I answered and I had letters to the editor. A lot of it was tattling my siblings and asking for things I wanted. Like the letter to the editor was like, the editor would really like a cuddly rabbit for her birthday. But that was really eyeopening to me that I didn't include things that I write about now all the time related to being Pakistani American. People tell me I make them hungry in my books by all the food I include, and I didn't talk about those things. And I really think I felt like I didn't have permission because I didn't see it written anywhere else. No one wanted to know about those things. The whole invisibility thing I mentioned earlier.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Even for yourself, even writing your own stories, your own work and stuff when you were younger, it's like you're just conditioned in a way.

Hena Khan:

Totally.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you have a desire to be a writer? Did you see that as a future path for yourself? Or at what point were you able to realize you wanted to be a writer if not when you were little? Was it a dream?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I was really lucky that I had some encouragement. Well, reading from my mom of course, and then I was in a combined fifth, sixth classroom that was I guess gifted and talented they called it back then. And our language arts teacher was just so creative and she really pushed writing in a way that I don't know if they're really doing nowadays. And she also made us perform. We did theater. It was really great. I do remember writing at home. And those writings were private. Even though it was a family newspaper, nobody really read it. I don't remember sharing it even with my parents.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, really?

Hena Khan:

So ironic. Yeah. I don't think I ever, like I said, considered it as a profession. I did think it was something I was okay at over time. In high school, I tried out for my school newspaper and that actually made me think of journalism as a potential career in college. But somehow someone had told me, "Well, if you major in journalism, you're going to be taught to write in a very specific way, so you should major in English instead or something else." So I ended up majoring in government and politics and then got very interested in working in the field of development and saving the world and whatever I thought I was going to be doing. So I put the writing side of my life on hold, but then when I started actually working, I found that everywhere I went, I would be the person doing the writing. The annual report or whatever it was.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The grant writer or whatever.

Wrestling perhaps with imposter syndrome, it took Hena years to recognize the potential of turning writing into a career. It actually wasn't until someone else acknowledged her capabilities that she first began to believe in herself.

Hena Khan:

It wasn't really my own idea. I credit my friend from elementary school. Throughout school we did our projects together and she was in that same little program with me and throughout high school we were on the school paper together. I was home with my son and taking a break from international public health work, and Andrea reached out to me. She was working for Scholastic Book Clubs. And she was doing the continuities department where you'd sign up for a book of the month and get a kit. And that's what she invited me to work on. Actually, to rewrite a couple of books. Well, one at a time. To rewrite a book in the Spy University series that she was spending a considerable amount of time rewriting, and then they eventually hired me to finish the series. So I did a few more and then went on to work for other series for them. And it was the only thing that made me think ... When we got our first fan letter, I thought, wow, an actual kid is reading something that I wrote. Even if you can't find it in a bookstore and you have to order through Scholastic and have it mailed to your home, it's there.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

But even with this clear indication that she did in fact have the potential to make a career out of her passion, Hena still needed another push. This time it came from wanting her son to see himself in stories.

Hena Khan:

Again, it was my friend, really, honestly. I had so little faith in myself I guess. But I had mentioned to Andrea just as a friend and as a mom that, "Oh, there's still no books out there for my kid." And I saw other good nice multicultural books out there, but nothing about Muslims or people like me. And she went to ... And at the time I just remember her saying, "Oh, I was at this librarian conference." And now I'm thinking, oh, it must've been ALA or TLA. I don't even know what it was at then. But she came back and she's like, "They were calling for Arab American and Muslim American literature. You should try." So again, it was her encouragement that made me think, okay, what could I possibly do? And I thought about a story about Ramadan because my son was at that point in preschool, and I saw how there was nothing to share with the class about what Ramadan was. I didn't want him to have to go through life saying my religious holiday or my special month of the year. So that really was it.

Then I thought, okay, how could I write something about Ramadan that's not an Islamic book, which I had a handful of those for him, which were horrid, really didactic and written by Muslims about Islam, but nothing for the mainstream. And also just something ... I very much thought school library. I want my kid to go into the school library and see their book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

To see this when it's the time to ... You know what I mean?

Hena Khan:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

To have that ... Anytime, but especially when it's like see yourself recognized.

Hena Khan:

Exactly. At that time I thought, okay, well that's fun. Even when I managed to sell that and that came out, I didn't really consider it a career. It was a side gig. A side hustle and I was still working in international public health. I don't think I had any faith in the industry to embrace me as an author or to want more from me. So every time it felt like beating down the door. And even the Ramadan book, it was, okay, here's a book about Ramadan, but how do I make it appealing to educators and how do I add value? Because the story about Ramadan alone is not enough. So here's a story about a girl watching the moon change shape over the course of the month, and I'm going to build in lunar phases-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Science tie in.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And then spoiler to everyone out there, she gets the telescope at the end, and I was like, okay, here's a stem angle here. And I was really trying whatever I could to make it as just accessible and friendly to people. I just didn't know if I'd ever get the chance again.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Eventually Hena realized that she didn't need to cushion stories about Muslim families to make them palatable to non-Muslim readers. She could just write about children, their worries, their joys, their lives, and that was valid enough, but it took time for her to truly believe it.

Hena Khan:

Honestly, it was very gradual. Especially those early years. Night Of The Moon came out in 2008, so that means I sold it in 2006. So this was well before We Need Diverse Books or really the recognition that there was this gaping hole in the children's literature leaving out so many voices. So people were starting to think about it, I'm sure, but it wasn't this major push yet. For me it was really one by one recognizing what I wanted to see exist. And so it started with the Ramadan book and then the concept book, and then I was like, okay, what else do I see? And I thought about the stories I loved to read as a kid, and like so many writers, write the book that you wish you had as a kid. And I think that's where Amina's Voice was born. I wanted to write a slice of life story featuring a Pakistani American family, and a lot of it was inspired by my friendship with my friend in elementary school and the whole idea of wrestling with identity, but that not being an issue.

I didn't want it to be in any way her feeling ... And I guess this is how writers write who they wish they were in a way. She didn't struggle with her identity the way I did as a kid. Her problem is confidence and wanting to sing and friendship struggles maybe were the closest thing she and I shared as people. And then I worked in the idea of the mosque vandalism because I saw that as an unfortunate situation that not only Muslims but Jewish communities and others were facing, and that had been a part of my childhood growing up. I live in a predominantly Jewish area. Or I shouldn't say predominantly, but heavily Jewish area and there was many synagogues. Five or six within a few mile radius of my home. So sadly, when I was growing up, I would hear about synagogues being attacked from time to time, and I remember the impact on the community and the heartbreak that would cause, and everyone rallying around to go paint over the graffiti or whatever it was. And I had heard about things like that happening in mosques. But I wanted for my character to have this connection to the mosque and for it to be this special meaningful place for her along with it being a place of boredom and forced religious education and all that stuff too. Keep it real.

But for that idea of what does it mean to have something so special to you as a community to be attacked in that way. But it wasn't-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The central point.

Hena Khan:

Supposed to be an issue. And yeah, it's not the beginning of the book, it's something that happens. And I remember when the book was marketed, they highlighted that as this big turning point moment for her or that being the big challenge in her life and I was like, "Well, not really. It's really a story about personal growth and friendship and finding yourself and finding confidence." But that was my motivation for putting that in. It was well, one upping the stakes and just making it ... In my mind, I thought knowing as a Muslim and living in a post 9/11 world, the questions people had, and even some of the suspicions people had around mosque and mosque communities, and that was part of my motivation too, was taking people into a mosque and showing them what really happens there. It's pizza fundraisers and it's whiny children and it's congregational prayer and things that are very, very familiar so that was important to me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Yeah. You've written so many stories now where Muslim kids are just existing, playing basketball, hanging out with friends, that kind of thing. So maybe this is a good time to talk about your upcoming middle grade novel Drawing Deena. And that character is actually navigating a lot of stress and anxiety that she's having trouble putting her finger on. So maybe we could talk about some of your inspirations for that book.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. It was a combination of things. It was my own anxiety to a certain extent. The story begins with Deena at the dentist because she's clenching and she's cracked a tooth, which I did in real life, and I wear a night guard now so that was completely coming from my own experience. And then a family member who was dealing with anxiety very much in the way that I described Deena's experience where it was very stomach centric and nobody understood what it was. And then slowly coming to realize that it was anxiety at play. And I feel like for so many kids, especially, that is the way it manifests is in the gut. You may not think that they have a reason to feel the way they feel. And I think as adults sometimes, and especially in my communities, and I know many immigrant communities, mental health stuff can ... It's not that it doesn't matter, but it's like, oh, you'll be fine. And I felt like it was something that I wanted to write about because I've seen it not only in my own family, but other families where it takes a while to come around and recognize it for what it is and then decide what to do about it. And sometimes getting outside support can be really met with resistance.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What are you hoping that readers are going to take away from that story, or also more broadly from your stories in general?

Hena Khan:

I think for me, it is this balance in the books that I write where I have the book's very specific about a specific topic, whether it's Ramadan or the Hijab, or my new picture book is about going to Friday prayers. So those are still what I would put in the educational category. And so you're learning about Islam or Muslim traditions, but then on the flip side, I just really wanted stories for kids to be able to see themselves and not have them be about wrestling with your identity or who you are as a Muslim or about being bullied or any of that, but just getting to be a kid, because that's what I loved so much as a reader when I was reading the Ramona Quimby books or Judy Blume books or just stories about kids grappling with life and kid challenges, whatever they are, or kid passions. And that's what I loved reading.

So for me, Amina's Voice was the first novel I wrote, but then when I wrote the Zayd series, I was like, I just want to write about a kid who loves basketball and who's this scrawny underdog whose stomach hurts a lot. He was based on my younger son. And I wanted to write his extended family and all the characters in that. And so even though it's sports heavy, there's still a lot of friendship and family and community and just a big fat Pakistani wedding that happens, and all the things that make our culture fun and interesting. And all the things I left out of my family newspaper as a kid, I cram into my books because it is the flavor and the color and the spice that we add to life. And that's where ... I don't know. The idea of having a book like More To The Story that's like in some ways this book that I adored so much, or the Zara series, which is really my tribute maybe to Ramona Quimby. It's very neighborhood focused and play focused and antic filled. And I just want the joy of reading.

Of course, there's light lessons or whatever you want to call it. Realizations and character growth, but it's not heavy or about overcoming, and they're not pain stories because I feel like life is hard. I want kids to just-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They're already anxious about many things, right?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And also, I want kids to feel proud when their class is reading a book about a character like them. It's not necessarily a book about struggle or trauma. It's about wanting to be the best kid on a basketball team or wanting to be the ruler of the neighborhood.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Yeah. You obviously connect with kids in this really big way. Actually, my son, Cassius, he dressed up like Zayd from your book Power Forward for his third grade book-o-ween party.

Hena Khan:

That is amazing. Oh my gosh.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And it was just adorable. He loved that series by the way. Do you have encounters with your other young fans that have really stayed with you?

Hena Khan:

Oh my gosh, yes. When I was in Seattle, they had put Power Forward, the first book of the Zayd Saleem series. It was not quite a Battle Of The Books, but it was some special reading program that the Seattle Public Library had done. And I was out there for school visits and I went and there was this little boy. He just had to get my attention while I was walking up to give my presentation. He said, "I just love this book so much. I love this book so much. It made me want to cry." And I thought, oh my goodness, that's the best compliment I've ever gotten in my life. Because really some of the ones that stick out the most are the kids from different backgrounds who identify so strongly. And the letters I get from people like these grandparents who talked about More To The Story and how their granddaughter was going through leukemia and how helpful they found the book. The sisters found the book so comforting. And those types of things where you're just like, there's these universal truths, like you said, specific details, but universal feelings and universal experiences that people hopefully can relate to.

And that's what I go for in all of my books, that common humanity. Hopefully anybody can get to know a Pakistani American family, maybe witness some Muslim traditions, but yet feel included too, the way I did in all the books I read as a kid and didn't wonder, where am I? It's like, no, you're there. You're with this family and you're glad to be there, and you wish you were one of those kids in that room or on that street. I remember that feeling so strongly. I wish I was one of the gang.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You want to be up there doing the plays with the March sisters.

Hena Khan:

Exactly. Exactly. And that to me, builds ... That gets us connected. And that's where you think about those characters later in life and that stays with you, I hope.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I hope too. And I think that bit about common humanity feels so crucial right now in this moment with the state of our world as it is. It's just so important for kids to see and understand and embrace other cultures.

Hena Khan:

Absolutely. And that's why in my books too, I like to include friendships. In the Zara series, which is very much I mentioned based on my neighborhood, my dearest friends who grew up with me across the street, the Jewish family, we grew up in each other's homes, we participate in each other's traditions. I would go over their house and eat matza crackers. It was just part of my life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Our food's not our strong suit to me. Besides bagels.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. Well, I loved food actually. They were like, "You like this?" I'm like, "Give me some more matza." But we understood each other and that came through play and from being in each other's homes. And that was really, really fun for me to write into the Zara series was this interfaith friendship because that was my reality. And it's not deliberate diversity or trying to send a message. That was my experience, and it just brings me joy to highlight that.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Okay. Hena, I was talking to one of my best friends, Halla, about having you on the show, and she was really excited because her twin boys love your Curious George book, and I promised her I would let them ask a question. So this is from her son Eyad. And for the record, Zidan also had a question about why you chose to write a book about Ramadan, but you already answered that one so I'm going to play Eyad for you. Okay, here he is.

Eyad:

My name is Eyad, and I have a question for you. My question is, how did you figure out Curious George would be the Muslim character in the book?

Hena Khan:

Oh, I love that. Oh my gosh. So cute. Well, the funny thing is, I remember when ... So the publishers, HMH, who put out new Curious George books, they actually approached me and said, "We have this series where Curious George celebrates other holidays like Christmas and Hanukkah and St. Patrick's Day and Halloween and Parade Day." And they're like, "We think it's high time he celebrate Ramadan. What do you think? Would you like to write this?" And I was like, "Yes." But then I asked them, I was like, "Well, so how does this work exactly? Is Curious George Muslim? Is the man with the yellow hat Muslim? What exactly are we doing here?" And they said, "Well, yeah." I was like, "I don't know." And they said, "Well, how about he's celebrating Ramadan with his Muslim friends?" And I was like, "Ah, got it. Okay. That totally works." It was super fun to write and have this icon like Curious George celebrate this meaningful time. It's been so well received by the Muslim community.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. And the Muslim community and beyond, honestly. And speaking of beyond, I think as a writer, you've obviously really grown into embracing more broadly your South Asian heritage and I wonder in that vein, if you can tell me about your upcoming anthology.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I'm very excited about The Door Is Open, which is an anthology of stories written by South Asian American middle grade writers and a mix of writers from different parts of South Asia, from India, Pakistan, and people of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. So we've got Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Jewish, Christian, and it's just really fun that what unites us all is our culture as South Asians. And it's so strong, and I feel like as a Pakistani American Muslim growing up in the US when my parents moved here initially, there weren't too many other Pakistani families. And I remember one of my dad's first friends who he met, he actually took the QE2, the Queen Elizabeth 2 ship from England to America for fun when he could have flown. But he went on the ship and he met a Hindu man who became one of his closest lifelong friends. And it didn't matter that they came from rival countries or opposing religions the way it's presented over there, but they just had this instant bond and it was so sweet growing up with them. And that's what I wanted to capture in the book was that we're all desi, which is what we call ourselves. And we're all from the des and we all share a lot of commonalities.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I'm very excited. When is that coming up?

Hena Khan:

That'll be out April 23rd. And we've got some amazing Newberry honor winners. We've got Rajani LaRocca, Sayantani DasGupta, Maulik Pancholy, Mitali Perkins, Aisha Saeed, Reem Faruqi. A whole bunch of really, really talented authors.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Taking inspiration from The Doors Is Open, Hena's reading challenge, Read Desi, is all about celebrating South Asian American writers.

Hena Khan:

So the anthology has so many writers who I really adore, which is why I picked them. They're all writers whose works I read and really connected with. Veera Hiranandani who wrote The Night Diary, which is one of my favorite books, opens up the anthology, which I'm so proud to have her be a part of it. And I just think these writers have written books about being a desi American, like my books. Maulik's book, The Best At It is hilarious and just really fun. And Sayantani's got fantasy series with Indian mythology. Aisha's got both books set in Pakistan and in the US. Same thing with Mitali. So it's just a really nice mix of books where you get to see different aspects of South Asian identity and history and how kids are experiencing life in America today. And then there's a mix of wonderful picture books by these authors too. So reading for all ages.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You can find Hena's challenge and all of our past challenges from authors such as Daniel Nayeri, Kate DiCamillo, Jacqueline Woodson, and even recent National Book Award winner, congratulations, Dan Santat at thereadingculturepod.com.

And today's Beanstack featured librarian is Allie Buffington. She is a library media specialist at Holley-Navarre Intermediate School in Santa Rosa County, Florida. Allie tells us about the importance of making the library a space that kids want to come back to.

Allie Buffington:

I try to remember my physical presence. The way that I portray myself and the library space is going to stick with them for a very long time, and that's going to be directly correlated to how they remember their experience with books. I feel like my purpose in life, my purpose in this library is to try and get those fifth graders to walk out my door at the end of the year and want to walk in the new doors of the new school's library. Because we know middle through high is that critical point where we start to lose the interest in the reading. And so I told a kid the other day, I'm not super strict on the library rules. Like the shh, be quiet. One of my kids the other day was like, "Oh, I didn't bring any of my four books back." And I was like, "Well, I guess you get a fifth one today." I told him, "I'm a librarian for the people and not for the books. I'm here for you guys."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture and you've been listening to our conversation with Hena Khan. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride and The Blackwoods by Brandy Colbert. If you enjoy today's episode, please show some love and give us a five star review. It just takes a second and it really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com. And remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and insights. This episode was produced by Jackie Lanport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josiah Lamberto-Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.

And this was something that was very eyeopening to me in terms of realizing the power of representation is that I very much whitewashed my own family newspaper.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Kids absorb a lot. They're kind of famous for it. We've all talked about the little sponges soaking up language and facts about dinosaurs and occasionally social graces. But some of the messages kids absorb are too subtle for them to label and when they're harmful, those can be the hardest to root out. Hena Khan grew up feeling that her heritage and her immigrant family's experience simply weren't important. That the things that made her different from her white suburban peers were better left, well, ignored. And she would internalize that message for years to come. But then in a poetic moment, she opened a book to read and saw her own mother reflected in its pages and she realized what she'd been missing out on. Today, she's a prolific author who has made it her mission to showcase families like her own, both in their differences and in their commonalities.

Hena Khan:

Hopefully anybody can get to know a Pakistani American family, maybe witness some Muslim traditions, but yet feel included too, the way I did in all the books I read as a kid.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Hena is a Pakistani American writer known for the groundbreaking and award-winning Amina's Voice, as well as its sequel Amina's Song. Her titles also include the Zara's Rules series, More To The Story and the beloved picture book, Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns: A Muslim Book of Colors, among many more. In this episode, she'll tell us about the sense of invisibility that she felt as a young reader, the long journey to having faith in herself and her perspective, and she'll also explain how in her unconscious search for books with Muslim immigrant families like her own, she somehow latched onto a book about Christian white sisters in the 1800s. You probably already know the one.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture. A show where we speak with authors and illustrators about the ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways at The Reading Culture Pod, and you can also subscribe to my newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter. All right, on to the show.

Why don't we talk a little bit just about your early childhood and what life was like in Rockville?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I grew up the child of immigrants from Pakistan. My father was one of the very early Pakistanis who moved here, so he came in 1959 and then went back and married my mom. And I was born and raised here in Maryland and grew up in the same neighborhood, the same house for my entire childhood and young adulthood. It's where my mother still lives now. So I used to walk to my local elementary school. And it was a really lovely neighborhood because we had a lot of diverse neighbors. And in fact, my new chapter book series, early middle grade series, Zara's Rules, is based a lot on my neighborhood. But I went to my local public school and I had a pretty uneventful childhood just balancing the normal challenges of being raised by immigrants and trying to figure out where I fit in and having the home life versus school life and private life versus public life.

But now people ask me and kids ask me a lot of times when I do school visits, if I was bullied as a child or what it was like for me growing up. And I tell them all the time that I didn't thankfully feel bullied or unwelcome in any way, but I think what I did experience was feeling a bit invisible. And not only because of books, because I didn't realize I wasn't in books until much later. But I think people just didn't know anything about where my family was from. If I mentioned Pakistan, people, teachers, administrators, kids, everybody was like, "Where's that?" A lot of times they hadn't heard the word Muslim, didn't know what that referred to when I was missing school because of the Eid holiday my parents would sign ... I would write a note actually and make my parents sign it. And I wouldn't even call it Eid because I just assumed nobody knew what that was. So I would just say, please excuse Hena for her religious holiday. That's what I referred to it as.

And I so desperately wanted to fit in, but then at the same time had this other side of me that I really didn't feel was very understood. And at the same time I was consuming the same media, TV, entertainment as everyone else. I was very familiar with Christmas and Hanukkah and all the other traditions and could carol like anybody. I would go caroling with my friends in the neighborhood. There was this sense of I tend to participate in and understand other people's traditions and experience, but nobody really knows mine.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. But you said you felt invisible is the word that you used. And how did that come out?

Hena Khan:

It wasn't like today where you see kids really proud of their heritage or encouraged to be. Maybe they still aren't actually. I know some kids probably aren't. But it's multicultural day or bring your culture to school day or whatever. That type of thing just didn't happen then. And it wasn't so much that I felt like people were being dismissive as much as they just didn't even know what to ask and didn't seem curious, and then I just didn't feel like I needed to share that part of who I was. I don't think I spent a lot of time thinking about it and I didn't really have the vocabulary. Now I look at the words that kids use and even things like culture. I don't think I even used the word culture as a kid. And certainly not words like identity or diversity or all of the terminology we have now to define ourselves. I wouldn't have even called myself a Pakistani American. The hyphenated identity wasn't a thing when I was growing up, so I was just different is what I felt.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And were you a big reader when you were growing up?

Hena Khan:

Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What was your reading life like?

Hena Khan:

It was very much imposed on me by my mother in a good way where she was a big proponent of reading. She would take us to the public library every few weeks with bags from the food store and we would fill them up and bring them home. Especially in the summertime, that was what we did. There were no summer camps or activities.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The library was your summer camp.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. It really was. And I'm so grateful for that because I became a big reader. And I think for me especially being this awkward, shy, self-conscious kid, to be able to immerse myself in books, of course just for fun and escape and companionship, but also just to learn about other families and how they functioned apart from what I was seeing on TV.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember some of the books that you were drawn to when you were younger?

Hena Khan:

I loved Beverly Cleary and she's still my literary hero. I read and reread the Ramona Quimby books and all of her stuff and probably checked those out the most when I was little. But I was a really wide reader. I read everything from fantasy to little mysteries. I loved realistic fiction. That was probably what I reread the most, but I don't remember being as picky as I became as I grew older. And I never actually stopped reading a book. If I didn't like it midway I just plowed through it and finished it because I felt like I couldn't not finish it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Well, you mentioned that you didn't notice until later that you were not in all the books that you were reading. Do you remember at the point at which you had a moment of recognition that you weren't seeing your own experience in pages?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I do. It was college. I was at the University of Maryland. I was an undergrad. And I was taking a lot of English classes and I remember taking a African-American literature class and I loved it. And then I took a Caribbean literature class. And at that time there was no South Asian literature class offered. But as I started reading some of these other books, I started looking and I found some South Asian women writers. And I remember being so surprised and pleased in a good way to see things that were familiar to me like a sari and a mango and the language and the culture, but it still wasn't mine. I felt it was set in India for the most part.

So that's when I became aware of the fact that ... I was searching and I read a whole bunch and I liked them to a certain extent, but I didn't love them until I read ... I think it was The Namesake. That was the first time I felt seen. And it wasn't even so much that I felt ... Because it's about a Bangladeshi American multi-generational family, and I definitely identified with the child, Googol, the boy, but what I really saw was my mother. And the opening chapters of the book are about the parents and the mother as a new bride coming to America and sitting in the little apartment trying to find spices to cook with and the intense loneliness that she felt and that just mirrored exactly what my mother used to describe her life like when she first came to the DC area and was living in an apartment in Silver Spring when my dad would go to work. It was that shock of recognition. I was like, this is my mother. My mother is in a book, and that was so powerful to see and that just made me so hungry for more.

"Jo scribbled away until the last page was filled when she signed her name with a flourish and threw down her pen exclaiming, 'There. I've done my best. If this won't suit, I shall have to wait until I can do better.' Lying back on the sofa, she read the manuscript carefully through making dashes here and there and putting in many exclamation points, which looked like little balloons. Then she tied it up with a smart ribbon and sat a minute looking at it with a sober wistful expression, which plainly showed how earnest her work had been. Jo's desk up here was an old tin kitchen, which hung against the wall in it. She kept her papers and a few books safely shut away from Scrabble, who likewise being of literary turn was fond of making a circulating library of such books as were left in his way by eating the leaves. From this tin receptacle, Jo produced another manuscript and putting both in her pocket, crept quietly downstairs, leaving her friends to nibble her pens and taste her ink. She put on her hat and jacket as noiselessly as possible and going to the back entry window, got up on top of the roof of a little porch, swung herself down to the grassy bank and took a roundabout way to the road. Once there, she composed herself, hailed a passing omnibus and rolled away to town looking very merry and mysterious."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Louisa May Alcott's Little Women was published in 1868, but to this day, the strong characters still feel just as palpable through the pages. In this passage, Jo is just about to submit her first article draft to be published in the paper. In the following scene she struggles with building up the nerve to go inside and hand over her work. It was the authenticity and rawness of the emotions and dialogue between Jo and Laurie that inspired Hena to write her book, More To The Story, which follows four young sisters in a Muslim American family in Georgia.

Hena Khan:

I just wanted to pull from my memories of what were the parts that spoke the most to me and the themes that I wanted to infiltrate my book, but I didn't want it to feel like a straight retelling. I wanted a fresh narrative, but with all the things I loved, like the relationship between Jo and Laurie. I wanted my friendship between my characters to feel as sincere and believable and then certain themes that maybe aren't significant to other fans of the book. For me, Jo's anger was something I focus on.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Despite being about a white Christian family in the late 1800s, Little Women became a favorite read and a book where Hena saw her own identity unexpectedly reflected.

Hena Khan:

Martin Luther King Library invited me to speak at an award ceremony for letters and literature, which is, I think it's a national contest where students write to authors living or dead who had an impact on them. And so I was reading the finalists for the competition and they were really moving letters and I was like, "Okay, what am I going to talk about during my comments?" So I thought about who I would've written to if I was in high school and what I would say, and I thought of Little Women. I thought of Louisa May Alcott and why this book resonated so deeply. And I realized that this is where I saw myself probably more than anywhere else in the books I was reading, because even though it was written 150 years ago, a lot of what was in here felt very familiar and comforting to me.

Things like the strict gender norms were recognizable to me. The respect for parents. That was something that always threw me as a teen, especially as a little kid, but even more as a teen, was watching teen shows and seeing the way kids could sass their parents and talk back and I hate you. That was unheard of. I couldn't even talk back, let alone say a bad word or express dislike for my parents. The respect for parents was so profound in this book. Even some of ... My parents had an arranged marriage and the marriage proposals and the expectations around dating and all of that was very familiar. And so it hit me later, I said, for someone probably hungry for representation, this was as close as I got for a while.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And then, well, I'm guessing ... I don't know. Did you identify with Jo?

Hena Khan:

Totally. I didn't realize that the book was not Jo's book. I knew it, that there were chapters told from the other sisters' perspectives, but I just got through those to get back to Jo's story. They felt like filler stories to me. So I was like, "Doesn't everyone identify with Jo? Are there really people who identify with Amy?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. No. Right. Okay. No.

Hena Khan:

But there must be. Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Of course. But interesting. Yeah. So there's both the recognition of the norms, but also identifying them as a young person. Questioning them.

Hena Khan:

Absolutely. Yeah. And I love the fact that she pushed back and felt like she was more. And the fact that she was a writer. I was a little writer too. And I actually wrote a family newspaper.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, like Jo.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And I didn't realize it until much later that, oh, that must be where I got the idea from. I don't remember getting the idea, I just remember doing it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you remember what your family newspaper was called?

Hena Khan:

Oh yes. The Khanicles.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

No. Do you have any editions of it still?

Hena Khan:

I do. Yeah. Actually there's a few lying around. I took screenshots of them. We found them in a box. I used to save my writings and they're on lined notebook paper that's yellowed with age written in my print.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

So good.

Hena Khan:

And if you read it, other than the names, there was nothing that made my family different from the March family or the Quimby family or any of the other families I was reading about. I had a section devoted to food, but I didn't talk about Pakistani dishes that my mother was cooking every day. I just spoke about food in a very general ... Like oh, mom's having a dinner party and she's cooking, and I didn't mention anything about being a Muslim, about our traditions.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Although it was like this major part of your life.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. Yeah. I had an advice column. People could write it. I wrote in and then I answered and I had letters to the editor. A lot of it was tattling my siblings and asking for things I wanted. Like the letter to the editor was like, the editor would really like a cuddly rabbit for her birthday. But that was really eyeopening to me that I didn't include things that I write about now all the time related to being Pakistani American. People tell me I make them hungry in my books by all the food I include, and I didn't talk about those things. And I really think I felt like I didn't have permission because I didn't see it written anywhere else. No one wanted to know about those things. The whole invisibility thing I mentioned earlier.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Even for yourself, even writing your own stories, your own work and stuff when you were younger, it's like you're just conditioned in a way.

Hena Khan:

Totally.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Did you have a desire to be a writer? Did you see that as a future path for yourself? Or at what point were you able to realize you wanted to be a writer if not when you were little? Was it a dream?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. I was really lucky that I had some encouragement. Well, reading from my mom of course, and then I was in a combined fifth, sixth classroom that was I guess gifted and talented they called it back then. And our language arts teacher was just so creative and she really pushed writing in a way that I don't know if they're really doing nowadays. And she also made us perform. We did theater. It was really great. I do remember writing at home. And those writings were private. Even though it was a family newspaper, nobody really read it. I don't remember sharing it even with my parents.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, really?

Hena Khan:

So ironic. Yeah. I don't think I ever, like I said, considered it as a profession. I did think it was something I was okay at over time. In high school, I tried out for my school newspaper and that actually made me think of journalism as a potential career in college. But somehow someone had told me, "Well, if you major in journalism, you're going to be taught to write in a very specific way, so you should major in English instead or something else." So I ended up majoring in government and politics and then got very interested in working in the field of development and saving the world and whatever I thought I was going to be doing. So I put the writing side of my life on hold, but then when I started actually working, I found that everywhere I went, I would be the person doing the writing. The annual report or whatever it was.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The grant writer or whatever.

Wrestling perhaps with imposter syndrome, it took Hena years to recognize the potential of turning writing into a career. It actually wasn't until someone else acknowledged her capabilities that she first began to believe in herself.

Hena Khan:

It wasn't really my own idea. I credit my friend from elementary school. Throughout school we did our projects together and she was in that same little program with me and throughout high school we were on the school paper together. I was home with my son and taking a break from international public health work, and Andrea reached out to me. She was working for Scholastic Book Clubs. And she was doing the continuities department where you'd sign up for a book of the month and get a kit. And that's what she invited me to work on. Actually, to rewrite a couple of books. Well, one at a time. To rewrite a book in the Spy University series that she was spending a considerable amount of time rewriting, and then they eventually hired me to finish the series. So I did a few more and then went on to work for other series for them. And it was the only thing that made me think ... When we got our first fan letter, I thought, wow, an actual kid is reading something that I wrote. Even if you can't find it in a bookstore and you have to order through Scholastic and have it mailed to your home, it's there.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

But even with this clear indication that she did in fact have the potential to make a career out of her passion, Hena still needed another push. This time it came from wanting her son to see himself in stories.

Hena Khan:

Again, it was my friend, really, honestly. I had so little faith in myself I guess. But I had mentioned to Andrea just as a friend and as a mom that, "Oh, there's still no books out there for my kid." And I saw other good nice multicultural books out there, but nothing about Muslims or people like me. And she went to ... And at the time I just remember her saying, "Oh, I was at this librarian conference." And now I'm thinking, oh, it must've been ALA or TLA. I don't even know what it was at then. But she came back and she's like, "They were calling for Arab American and Muslim American literature. You should try." So again, it was her encouragement that made me think, okay, what could I possibly do? And I thought about a story about Ramadan because my son was at that point in preschool, and I saw how there was nothing to share with the class about what Ramadan was. I didn't want him to have to go through life saying my religious holiday or my special month of the year. So that really was it.

Then I thought, okay, how could I write something about Ramadan that's not an Islamic book, which I had a handful of those for him, which were horrid, really didactic and written by Muslims about Islam, but nothing for the mainstream. And also just something ... I very much thought school library. I want my kid to go into the school library and see their book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

To see this when it's the time to ... You know what I mean?

Hena Khan:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

To have that ... Anytime, but especially when it's like see yourself recognized.

Hena Khan:

Exactly. At that time I thought, okay, well that's fun. Even when I managed to sell that and that came out, I didn't really consider it a career. It was a side gig. A side hustle and I was still working in international public health. I don't think I had any faith in the industry to embrace me as an author or to want more from me. So every time it felt like beating down the door. And even the Ramadan book, it was, okay, here's a book about Ramadan, but how do I make it appealing to educators and how do I add value? Because the story about Ramadan alone is not enough. So here's a story about a girl watching the moon change shape over the course of the month, and I'm going to build in lunar phases-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Science tie in.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And then spoiler to everyone out there, she gets the telescope at the end, and I was like, okay, here's a stem angle here. And I was really trying whatever I could to make it as just accessible and friendly to people. I just didn't know if I'd ever get the chance again.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Eventually Hena realized that she didn't need to cushion stories about Muslim families to make them palatable to non-Muslim readers. She could just write about children, their worries, their joys, their lives, and that was valid enough, but it took time for her to truly believe it.

Hena Khan:

Honestly, it was very gradual. Especially those early years. Night Of The Moon came out in 2008, so that means I sold it in 2006. So this was well before We Need Diverse Books or really the recognition that there was this gaping hole in the children's literature leaving out so many voices. So people were starting to think about it, I'm sure, but it wasn't this major push yet. For me it was really one by one recognizing what I wanted to see exist. And so it started with the Ramadan book and then the concept book, and then I was like, okay, what else do I see? And I thought about the stories I loved to read as a kid, and like so many writers, write the book that you wish you had as a kid. And I think that's where Amina's Voice was born. I wanted to write a slice of life story featuring a Pakistani American family, and a lot of it was inspired by my friendship with my friend in elementary school and the whole idea of wrestling with identity, but that not being an issue.

I didn't want it to be in any way her feeling ... And I guess this is how writers write who they wish they were in a way. She didn't struggle with her identity the way I did as a kid. Her problem is confidence and wanting to sing and friendship struggles maybe were the closest thing she and I shared as people. And then I worked in the idea of the mosque vandalism because I saw that as an unfortunate situation that not only Muslims but Jewish communities and others were facing, and that had been a part of my childhood growing up. I live in a predominantly Jewish area. Or I shouldn't say predominantly, but heavily Jewish area and there was many synagogues. Five or six within a few mile radius of my home. So sadly, when I was growing up, I would hear about synagogues being attacked from time to time, and I remember the impact on the community and the heartbreak that would cause, and everyone rallying around to go paint over the graffiti or whatever it was. And I had heard about things like that happening in mosques. But I wanted for my character to have this connection to the mosque and for it to be this special meaningful place for her along with it being a place of boredom and forced religious education and all that stuff too. Keep it real.

But for that idea of what does it mean to have something so special to you as a community to be attacked in that way. But it wasn't-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

The central point.

Hena Khan:

Supposed to be an issue. And yeah, it's not the beginning of the book, it's something that happens. And I remember when the book was marketed, they highlighted that as this big turning point moment for her or that being the big challenge in her life and I was like, "Well, not really. It's really a story about personal growth and friendship and finding yourself and finding confidence." But that was my motivation for putting that in. It was well, one upping the stakes and just making it ... In my mind, I thought knowing as a Muslim and living in a post 9/11 world, the questions people had, and even some of the suspicions people had around mosque and mosque communities, and that was part of my motivation too, was taking people into a mosque and showing them what really happens there. It's pizza fundraisers and it's whiny children and it's congregational prayer and things that are very, very familiar so that was important to me.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Yeah. You've written so many stories now where Muslim kids are just existing, playing basketball, hanging out with friends, that kind of thing. So maybe this is a good time to talk about your upcoming middle grade novel Drawing Deena. And that character is actually navigating a lot of stress and anxiety that she's having trouble putting her finger on. So maybe we could talk about some of your inspirations for that book.

Hena Khan:

Yeah. It was a combination of things. It was my own anxiety to a certain extent. The story begins with Deena at the dentist because she's clenching and she's cracked a tooth, which I did in real life, and I wear a night guard now so that was completely coming from my own experience. And then a family member who was dealing with anxiety very much in the way that I described Deena's experience where it was very stomach centric and nobody understood what it was. And then slowly coming to realize that it was anxiety at play. And I feel like for so many kids, especially, that is the way it manifests is in the gut. You may not think that they have a reason to feel the way they feel. And I think as adults sometimes, and especially in my communities, and I know many immigrant communities, mental health stuff can ... It's not that it doesn't matter, but it's like, oh, you'll be fine. And I felt like it was something that I wanted to write about because I've seen it not only in my own family, but other families where it takes a while to come around and recognize it for what it is and then decide what to do about it. And sometimes getting outside support can be really met with resistance.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What are you hoping that readers are going to take away from that story, or also more broadly from your stories in general?

Hena Khan:

I think for me, it is this balance in the books that I write where I have the book's very specific about a specific topic, whether it's Ramadan or the Hijab, or my new picture book is about going to Friday prayers. So those are still what I would put in the educational category. And so you're learning about Islam or Muslim traditions, but then on the flip side, I just really wanted stories for kids to be able to see themselves and not have them be about wrestling with your identity or who you are as a Muslim or about being bullied or any of that, but just getting to be a kid, because that's what I loved so much as a reader when I was reading the Ramona Quimby books or Judy Blume books or just stories about kids grappling with life and kid challenges, whatever they are, or kid passions. And that's what I loved reading.

So for me, Amina's Voice was the first novel I wrote, but then when I wrote the Zayd series, I was like, I just want to write about a kid who loves basketball and who's this scrawny underdog whose stomach hurts a lot. He was based on my younger son. And I wanted to write his extended family and all the characters in that. And so even though it's sports heavy, there's still a lot of friendship and family and community and just a big fat Pakistani wedding that happens, and all the things that make our culture fun and interesting. And all the things I left out of my family newspaper as a kid, I cram into my books because it is the flavor and the color and the spice that we add to life. And that's where ... I don't know. The idea of having a book like More To The Story that's like in some ways this book that I adored so much, or the Zara series, which is really my tribute maybe to Ramona Quimby. It's very neighborhood focused and play focused and antic filled. And I just want the joy of reading.

Of course, there's light lessons or whatever you want to call it. Realizations and character growth, but it's not heavy or about overcoming, and they're not pain stories because I feel like life is hard. I want kids to just-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They're already anxious about many things, right?

Hena Khan:

Yeah. And also, I want kids to feel proud when their class is reading a book about a character like them. It's not necessarily a book about struggle or trauma. It's about wanting to be the best kid on a basketball team or wanting to be the ruler of the neighborhood.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. Yeah. You obviously connect with kids in this really big way. Actually, my son, Cassius, he dressed up like Zayd from your book Power Forward for his third grade book-o-ween party.

Hena Khan:

That is amazing. Oh my gosh.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And it was just adorable. He loved that series by the way. Do you have encounters with your other young fans that have really stayed with you?

Hena Khan:

Oh my gosh, yes. When I was in Seattle, they had put Power Forward, the first book of the Zayd Saleem series. It was not quite a Battle Of The Books, but it was some special reading program that the Seattle Public Library had done. And I was out there for school visits and I went and there was this little boy. He just had to get my attention while I was walking up to give my presentation. He said, "I just love this book so much. I love this book so much. It made me want to cry." And I thought, oh my goodness, that's the best compliment I've ever gotten in my life. Because really some of the ones that stick out the most are the kids from different backgrounds who identify so strongly. And the letters I get from people like these grandparents who talked about More To The Story and how their granddaughter was going through leukemia and how helpful they found the book. The sisters found the book so comforting. And those types of things where you're just like, there's these universal truths, like you said, specific details, but universal feelings and universal experiences that people hopefully can relate to.

And that's what I go for in all of my books, that common humanity. Hopefully anybody can get to know a Pakistani American family, maybe witness some Muslim traditions, but yet feel included too, the way I did in all the books I read as a kid and didn't wonder, where am I? It's like, no, you're there. You're with this family and you're glad to be there, and you wish you were one of those kids in that room or on that street. I remember that feeling so strongly. I wish I was one of the gang.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You want to be up there doing the plays with the March sisters.

Hena Khan:

Exactly. Exactly. And that to me, builds ... That gets us connected. And that's where you think about those characters later in life and that stays with you, I hope.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I hope too. And I think that bit about common humanity feels so crucial right now in this moment with the state of our world as it is. It's just so important for kids to see and understand and embrace other cultures.

Hena Khan:

Absolutely. And that's why in my books too, I like to include friendships. In the Zara series, which is very much I mentioned based on my neighborhood, my dearest friends who grew up with me across the street, the Jewish family, we grew up in each other's homes, we participate in each other's traditions. I would go over their house and eat matza crackers. It was just part of my life.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Our food's not our strong suit to me. Besides bagels.

Hena Khan: