About this episode

Doing is a gift, the purpose of doing is an obligation. As a writer, Daniel Nayeri is well aware of the impact he has on readers. There is perhaps no more intimate power than becoming the dialogue in one’s head, and he feels strongly about using that power to have a positive impact on those who read his words. Part of his purpose, or obligation, he believes, is to “re-mystify the world.” Just wait until we talk about why cherries grow in pairs!

"Don't follow your dreams if that's the only thing you're doing. Ask yourself, what will make you most useful? What will make you most, in terms of a purpose, help you do meaningful work?” - Daniel Nayeri

***

Contents

- Chapter 1 - The Ferris Wheel and The Storyteller (2:15)

- Chapter 2 - A Retired Conan the Barbarian (6:43)

- Chapter 3 - Alberic The Wise (11:30)

- Chapter 4 - Remystifying the world (7:18)

- Chapter 5 - You get a memoir! And you get a memoir! And… (25:25)

- Chapter 6 - How to be interesting (28:20)

- Chapter 7 - Wise Shorts (33:31)

- Chapter 8 - Beanstack Featured Librarian (34:32)

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

Somewhere in this little heart was the desire to be good at this, and was the desire to discipline myself at the craft of it, at the exactitude of how challenging it can be to work through the skillset of storytelling, of writing all these things, but then of course, past that is, what is the effect of that purpose?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When snaking around the bend of the bookstore line at the National Book Festival this year, I recognized Daniel Nayeri walking by. We struck up a conversation, and once he met my son, Cassius, we took an erudite turn to talking about nominative determinism, or the theory that your name can determine who you are or become. It was a deep conversation, and Daniel had my whole family rapt, after just a few moments of discussion. See, even when discussing facts, he's a storyteller.

Before fleeing Iran, Daniel went by his Persian name, Khosrou, and when I looked up its meaning, I found it to be king. You'll hear in this episode that Daniel is the king of storytelling. You simply cannot ask him a question without getting a story for an answer.

For many years, Daniel was a beloved publisher, but he's best known for his Printz Award-winning memoir, Everything Sad Is Untrue, and more recently, for The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams. See, even each of his titles is a tale within itself.

In this episode, Daniel recounts how a roadside storyteller became one of his major influences. He warns us that our most precious memories may not actually be ours at all, and he encourages us to try our hand at the dinner game he plays in an effort to re-mystify the world.

My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and illustrators about ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities. We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more.

Make sure to check us out on Instagram for giveaways @thereadingculturepod. You can also subscribe to our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter. All right, onto the show.

Let's start with Iran. Can you tell me a bit about growing up there, and specifically, what was reading and storytelling like for you during those years?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, I was born in Tehran, Iran, but raised in Isfahan. From zero to five, that was where my life was. And as you can imagine, if you're a teacher, zero to five is just coming up on kindergarten. It was an era of my life that I remember almost completely without writing and reading. I hadn't learned that just yet, and there was some disruptions around that time. So yes, I was born and raised in Isfahan, but my mother converted to Christianity when I was five, and so we had to escape as refugees.

As a result, my dad chose to stay, he's Muslim, and so him and his family and my mother's family on that side, they're all in Iran, and so every memory I have of them is from that window of time. And as a result, all my memories are memories of sort of what I guess scholars would say is the oral tradition. I remember sitting on my uncle's lap and listening to stories. I remember going to this one individual's house in the village where my grandfather lived and he was famous as a storyteller and we would sit on the carpet in front of him, drink tea, and listen to him tell stories. I was in that age where I was ravenous for that sort of thing, bedtime stories, TV too. Right? But all of those were the ways that I was taking in the world around me, but not in writing and reading, I hadn't learned that yet.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. So storytelling played a bigger role. Can we go back and just talk a little bit about that storyteller? Can you tell me more about him?

Daniel Nayeri:

Actually, I have a picture book coming out about this experience because it was such an important one in my memory as a kid. So, we lived in Isfahan. Isfahan is a city. It's an ancient city. I was just recently writing a book about the Silk Road in the 4th century. There's a lot of culture there, there's a lot of history there, but outside of the city is an area called Ardestan, and that's much more rural, it was a, we might call a village, right?

In Ardestan was where my father's father, my grandfather had his farm and his land. It was always a long drive. It was always, in the summer months, it would be really hot and we had one of those really old giant cars. I guess I always thought of it as like a big adventure to go out there. But halfway when you were getting to a Ardestan, there was a gentleman, and he and his wife... In my story, I name him Abbas.

And so Abbas and his wife always wanted kids, but they weren't able to have them, and so Abbas had this just really joyful, childlike spirit and he was also very handy and he would use scrap metal to build toys for kids. So imagine, kind of a rough shot, but like a scrap metal teeter totter or a seesaw and that sort of thing.

And the big achievement had been that he had made a Ferris wheel out of scrap metal. So for me, it was this Ferris wheel in the desert that you would go to and all the kids would beg him to ride it. It's the kind of Ferris wheel that you have to hand crank, right?

This is for little kids to kind of go in a small circle up and down. Nothing like the World's Fair Ferris wheel. Nothing like that, but it was magical to me. Nothing short of outside of grocery stores or delis, you see these little horses that you can put a quarter in and ride. It's great.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Daniel Nayeri:

So we would go there, but Abbas always was known as telling these just incredible stories. And so the one I remember best is a fairytale that I've finally tracked to the Romanian, Hungarian region, like Russo Persian space. North of Iran has a lot of this kind of cultural crossover.

He would tell stories like that, and he would also sort of tell the classics, which to us were all the Arabian Nights classics, the Aladdin, and Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, and Sinbad, any of these kinds of things.

So storytelling, I go back to him a lot. I go back to the way we tell stories, and stories within stories, which is how the Arabian Nights works. It's the way I tell a lot of my stories, if not all of them. A lot of that comes from sitting in that little courtyard, listening.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

While Daniel was enchanted with oral storytelling, his relationship with the written word was less magical. Arriving in America, just learning to read, he was introduced to books mostly as a pragmatic means to pick up a new language and to fit in quickly.

Daniel Nayeri:

One of the ways I learned English was that we went to the library, and we had a 35 picture book limit, so we stack them all high and take them home, and I'm reading picture books. And for me, reading was always coupled with language acquisition, with trying to understand what is going on.

Obviously, the motivation is any kid on a playground wants to know what's going on, wants to be able to play, wants to engage with the other kids. And so because there was no ESL program, it was left to the books to do that. So reading was always a very strong tool in my head. It was very much a way to enter into everything, from friendships on a playground to better grades in school.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It wasn't until the sixth grade that a book grabbed Daniel's attention with the same electricity that he remembered from that village storyteller.

Daniel Nayeri:

The first time I discovered that a written book could have the experience of that storytelling was actually kind of later. It was when I started reading Terry Pratchett and things like that, like fairytales, or later on it was a surprise. I was like, "Oh, this is that."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. What did you read by Terry Pratchett?

Daniel Nayeri:

Oh, I can tell you. In the sixth grade, I read a short story by Terry Pratchett that I don't even think Pratchett scholars, Pratchett fans would call his best short story, but it was my first experience with him and it blew my mind. It's called Troll Bridge. It's only about nine pages long and it's about one of his characters. He has a character that is a lot like a Conan the Barbarian type. He's a barbarian, but the funny thing, because Terry Pratchett is hilarious, is that he's very, very old. He's kind of in his 90s and he needs to retire. His bones are always aching. He's not this sort of vision of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his prime. And he has a horse who's a very sarcastic horse and he talks to him, they're like a buddy cop, buddy barbarian kind of story.

Anyway, it's a short story about him, and he and the horse are freezing as they're walking through this winter night. They come across a bridge where a troll jumps out. And instead of the classic thing that should happen, which is the troll demands payment to cross the bridge or they fight or whatever, they end up sitting on the bridge together and just kind of commiserating because the world ain't what it used to be and trolls are... The business is real bad ever since his brother-in-law built a much bigger, nicer bridge down the way.

And so now he's not really doing well, and they kind of start having this classic old men, "Get off my lawn," kind of talk. The horse is just rolling his eyes the whole time, and they strike up a friendship. There was something so disarmingly funny about it. It's almost all dialogue. I couldn't believe, to me, fantasy was this serious place where Hobbits and Tolkien and all these things were, and he was just completely zigging where everybody was zagging. And so I fell in love with the idea that you could be that funny in a story.

Great storytellers, I just realized I'm thinking of this right now, are kind of like standup comedians in the sense that they kind of do crowd work. There's a lot of comedy built sometimes into storytelling, especially the way I remember it. There would be teasing of the little kids, and the voices of course are always kind of charming and funny. Sometimes there's a recurring joke, that in some ways is at the expense of one of the kids sitting there.

There's a lot happening in the space when oral stories are being told and it's almost always really charming and funny. That's the purpose of this kind of standup. A lot of what I had read was particularly sincere or serious or things like that, 'cause I loved fantasy. Terry Pratchett was the one who made it all funny.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's irreverent and you've got the-

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah.

Daniel Nayeri:

Once I read Troll Bridge, I wanted to write. I remember being like, "I want do what he just did."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's interesting, I'm thinking about the standup analogy. Just when you think of older people telling that story and you're like, "Here comes this part." You've heard it in your family, but it is like a bit worked on. That story's been told. And as a kid you're like, "Oh, telling this one again." But you know it's coming and you wait for everybody to laugh or whatever at that moment, and it is very much like a little routine. Or sometimes not a good one, but still they're telling the story again in their mind.

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, they have their punchlines and their format, and yeah, I love it, I love it. So, written stories hadn't done that for me until then. "I'm not a glass maker, nor a stone cutter, nor a goldsmith, potter, weaver, tinker, scribe, or chef, he shouted happily, and he leaped up and bounded down the steep stone stairs. Nor a venter, carpenter, physician, armorer, astronomer, baker or boatman. Down and around, he ran as fast as he could go along the palace corridors until he reached the room in which all his old things had been stored. Nor a blacksmith, merchant, musician, or cabinet maker, he continued, as he put on the ragged cloak and shoes and hat. Nor a wise man or a fool, success or failure. For no one but myself can tell me what I am or what I am not."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That was from Norton Juster's short story, Alberic the Wise, first published in 1965 Alberic, who has spent years wandering unsatisfied from one job to another, likewise rejects the role of village wise man and decides to resume wandering, possibly a purpose in and of itself.

Now, most of the authors on this show read us passages that they really identify with, but Daniel doesn't necessarily like Alberic's approach. In fact, when he read this story as a student, he felt like Alberic, in hunting for his true passion, had kind of gotten it all wrong.

Daniel Nayeri:

In one of the programs that my mom put me in that I will forever be grateful, is Junior Great Books. They're full of these short stories, a lot of them classics, some of them like The Brave Little Tailor and the Three Little Pigs, but some of them just off the beaten path kind of stuff.

And what you would do is you were supposed to read these and then one recess every month you would go into a teacher's classroom, and it was kind of like a book club for kids. You would read the short story and then come and you would sit down and you'd talk about it. And it was the first time I ever got the experience of having those kind of deeper talks with anyone about a story. And I had a particularly good teacher and she would ask just one more question, "What made him so brave?" Or, "What made him so clever?" Or, "What is it that you like?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, right. Sounds like a good teacher. So this story by Norton Juster is from Junior Great Books. And what did you take from it having this new analyzing skill that you did?

Daniel Nayeri:

I think one of the first things was that he realized very quickly that, or in the story, that he had been affecting his judgment of what would be a worthy pursuit based on how good he was at it, as opposed to how much usefulness he might derive from it. My perspective of that story is sort of his purpose in life, he's a character who's looking for his purpose, will not be derived from which he loves the most. It's not going to be a case of... My hot take is always, don't follow your dreams if that's the only thing you're doing. Ask yourself, what will make you most useful? What will make you most, in terms of a purpose, help you do meaningful work? Work that will have a good effect, whether in your family or your community for yourself, for your surroundings and your loved ones, right?

So, in a lot of ways, Alberic is beginning with this me first question, right? "Well, I love stone cutting. Let me go look at that." And he does it and it's good. There's nothing unsatisfying about becoming a good stone cutter, but ultimately it's not fulfilling a need in him to be purposeful and useful. And so I thought, yeah, it was one of those early looks at needing to look beyond myself and beyond my own interests or anything like that necessarily, and asking, how do you acquire a purpose?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And did that really connect with you? Did you feel like purpose was a really important part of your life growing up?

Daniel Nayeri:

When you say a phrase like purpose, sometimes it makes people think of dystopian YA, where some committee somewhere at some reaping or choosing or giving or tribing will tell you your purpose in a society and then you're like, "Oh no, I'm the tax accountant for our dystopian society." And you're like, "But I'm so cute and there's two boys after me, so I have to become a rebel."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right, right, right.

Daniel Nayeri:

I'm joking. I love those stories, we laugh. And for what it's worth, in traditions that we kind of also question sometimes, where you're told the exactitude of your purpose. That is uninteresting to me. And what exactly is your purpose is, of course, the external world is going to have almost no clue what yours will be. I'll try to be specific 'cause I might be dealing in abstractions.

I knew that in my heart I wanted to be a writer, I wanted to be a storyteller. That had been given to me. Whether that was the circumstances of being raised around some of these storytellers and stories that I just said, or whether because it was a great calling or my fate, whatever we want to say about it. But then of course, past that, is what is the effect of that purpose and what is the method? What are you doing with your skillset?

I would ask this question of someone who's calling us to make Faberge eggs. This isn't just for writers. Stories like Alberic the Wise, I think, help us disentangle those two. "Well, my mom says I should be a doctor, so that's my purpose." It's like, well, Alberic here is starting to actually ask himself these questions of the difference between your vocation and your obligation.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

"If we can just rise to the challenge of communication here in the parlor of your mind, we can maybe reach across time and space in every ordinary thing to see so deep into the heart of each other that you might agree that I am like you." That's a quote from Daniel's memoir, Everything Sad Is Untrue, and it's a nice summation of what he considers his own purpose, not the purpose of simply writing stories, his vocation, but the impact that the words have on those who read them, his obligation. Exploring the intimate relationship between author and audience was the next step in his journey.

Daniel Nayeri:

So that passage is, to me, in some ways reacting to this phrase I heard when I was in college, which was, "The author inhabits the reader." And when you pull that phrase apart a little bit, it's thinking about the idea of the author is quite literally putting words in the reader's mouth. They are going into this book and listening to this person, quite passively. They don't get to speak back. And that's a big theme in this book, that they're being forced to listen, and that's the nature of every written story, that the author is going to inhabit the reader. And I think that's a really fertile theme.

By the way. I think that's why people will throw a book across the room sometimes. When you are finally fed up with having to listen and to be inhabited by someone, not even necessarily the narrator, but with an author that you start to feel is misusing his or her privilege to be in your head, you forcefully kick them out. And I think that's a really powerful vision that people have, especially readers. People who've read a lot of books have done this more, obviously, and they know that they're selecting authors to come into their mind.

My narrator calls it the parlor of your mind. And the reason he does that is because conflating a different theme in that book, which is of course immigration and refugees. They also come into your country, they come into your community, into your spaces. And he's very cognizant as a writer, as a storyteller, of wanting to assure you that he's going to come in and he's going to be a good guest. He doesn't know how to tell stories, he actually doesn't even know how to be a citizen. He's a kid. But he has this sort of deep anxiety of wanting to be in a harmonious relationship with you, the reader. Wanting to please you, wanting to entertain, but also wanting to be welcome. And it's really, really important to him that he be, at the end of all this, welcomed by the reader.

Clearly, this is like a young refugee kid reflecting those same ideas about immigration, wanting to be welcome in Oklahoma and those kinds of... Later in the story, he says a line that says, "Every story is the sound of a storyteller begging to stay alive." Because he's starting to put all of this theme into crystal clarity for the reader, which is you are deeply powerful, you can throw me across the room anytime you want, you can pay me no attention and effectively kill me as a narrator, but even as an author. I am just overjoyed anytime I get letters from readers. It's challenging, I'm not great at email, I'm not great at writing, and each of them is a challenge for me to write back to. And yet, I'm overjoyed, because fundamentally, these are all my bosses. These are the only people who are ever going to give me the opportunity to write more and publish more books.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah. You clearly feel this sense of responsibility, and like you said, there's this obligation to do right by your readers. And I'd love it if you could talk more about the purpose behind your writing and some of those specific responsibilities that you feel as an author.

Daniel Nayeri:

A recent story I just wrote was called The Many Assassinations of Samir, the Seller of Dreams, and it's set on the Silk Road, and it's about this young monk, this boy who is asking all the big questions. And he's also realizing that his master, this Samir, the seller of dreams, is kind of a huckster. He's a con artist, he's this merchant who tricks people.

And there's some scene that I really thought was the centerpiece of the story, which is where he's trying to describe to this blacksmith and his daughter, one of the questions, the mysteries of his young life. And he's describing these two birds, and they were in love with each other and one of the bird dies, and the second bird is so distraught that he dies the next day.

And he is stuck with this question, this little boy, which is, what did that second bird lose? What did he lose that was so much more powerful than life and death, that upon losing it, he just gave up the ghost? And the blacksmith's like, who's kind of a cynical, comedic character is like, "Well, what do you think it was?" And the boy is forced to say the thing that every author is loathed to do, which is, "Well, what's the answer then?" And the answer always, of course, it has to be love.

And so this little boy, very naive, doesn't worry about cliche, just says it. He's like, "Well, I think what he lost was love." And the blacksmith just laughs in his face. And the reason he laughs in his face is because as adults, we've become immune to these simple truths. We are bored by them. Well, we call them cliches, we think they're so below us. But that is the simple truth in this little boy, this little monk's life.

I think an author's job, in some ways, is to find a way to remystify a lot of these things that we have become bored by, the simple truths that we have. What was it, Alexander Pope who describes poetry as, "True wit is nature to advantage dressed, what oft was thought, but never so well expressed," which what often was thought, but never so well expressed is what he thinks is true wit.

And it's true. We've all had love in our lives, we've all had heartbreak, we've all had that funny moment, whatever it might be, but a writer's job is to make it such that it was never so well expressed, this common thing. So to remystify the world, in some ways, I think... We live in the information age, we live in an age where very few people want to live in mystery. If you're in a restaurant with somebody and you ask-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, everything feels knowable.

Daniel Nayeri:

It's so knowable. And unfortunately, it's so boring. Sometimes, one of my favorite games at a restaurant is to ask a question that's kind of slightly stupid. Something like, "Why do cherries come in twos, what's up with that?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And who's going to pick up their phone and [inaudible 00:23:50]-

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, but and everyone does. Everyone is like, "Well, we don't..." And their immediate move is to, "Well, let me get the supercomputer out of my pocket and I'll find out for you." And I'm like, "No, no, no, no, no. You tell me what you think, you tell." And that's when it's really fun because you're like, "Oh, all this time you've offloaded the world and the mystery and curiosity into this little box."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Is that cherries coming in two one, one that you actually-

Daniel Nayeri:

I don't know, I just came up with it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Now I'm thinking about it, but okay. All right. Go ahead.

Daniel Nayeri:

It's a good one, right? I don't actually know. There's probably some-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's a good one.

Daniel Nayeri:

... reason with the golden ratio or something, who knows? But I think about these kinds of things and these moments as what if we let ourselves live in mystery just a little bit. I don't need the Wikipedia on plant growth patterns. I really just want to think about the fact that maybe those cherries are in love. I don't know, who knows? Just leave me to my un-Googled mystery, please.

The metaphor you'd have to use is signal-to-noise ratio, right? I guess what I'm trying to say isn't that I'm anti information, I just think there's a lot of noise in that kind of space, and I enjoy a quieter, sometimes more mystified space. Obviously, at the end of the dinner, if there's a real question, it's glorious that we can all pull out a computer and answer the actual scientific answer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, you can check our show notes for why cherries grow in two, in pairs.

Daniel Nayeri:

'Cause they love each other. You already answered this.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

All right, all right. Sorry, it's just repetitive. I wonder about schools and students and how some of your works, I don't know if you've been able to do any visits. I know that when Everything Sad Is Untrue came out, it debuted and it was COVID, right? So you probably didn't get to do as many visits, I'm guessing. So I don't know, between either of these beautiful books, have you had any experiences, interactions with kids that are memorable, one or two that really stand out for you?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yes, I've gotten to go to a lot of schools and my favorite thing about Everything Sad students or readers is how many of them are like, "Well, I'm starting to write my memoir now." And I always find it so delightful because you'll have sometimes a sixth grader, seventh grader, eighth grader, and they're starting to say that. And it's delightful because at first we think like, "Ha ha, they've only been alive for 14 years." But what I love about it, in fact, is that not only is it an incredibly great project to take on, but what they end up being is the chronicler for their family.

Because the first task, one thing I always tell them is, "Cool." I have a little thing I do called a one-page memoir with my students when I come to visit. And it's exactly that. It's, "Tell me a memory," it's just one memory, "Where you had other people were there. Okay, tell me what happened. Just who, where, why, and when, nothing too complicated. Make it an event. Don't be alone in the woods. Have it be like a 4th of July celebration, somebody's bar mitzvah, whatever. And now, go to someone else so that that evening their homework is to go someone else who was in that memory and just read them your memory and see what they say."

And they do. And every day, the next day it's a workshop, the next day I come back and I'm like, "Did anybody have anything weird happen?" And I can't tell you how many times someone will raise their hand and be like, "Yeah, my dad said that that wasn't even my memory, it was my grandma and I just thought it was mine and it was just a family story that I thought I had lived." And I'll be like, "What?" These giant things, not small gaps and reversals and people just... Everybody remembers things completely differently, and so to begin asking the questions about where their family comes from, what they value, who they are, I just love that stuff. So yeah, that's my favorite, just when people start going into their own. And a lot of them will write to me and tell me. I get these long, long emails that are like, yeah, they're family histories.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

They're giving you their memoir, they're telling you their memoir?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, they will give me a lot of... And it's hard to write back 'cause you can't just write back, "Cool, thanks for reading."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

"Very good."

Daniel Nayeri:

You have to engage. You have to be like-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

"Excellent work."

Daniel Nayeri:

"Hey, that's amazing that you found that out about your uncle or."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, you're an editor and a pub... Yeah, that's like your trade, right? You can't even begin. What will you do with the [inaudible 00:28:08].

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah. Yeah, the jerk version of me just sends back a thumbs up emoji. It's a good job.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

We've already been given a peek of a few of the upcoming stories from Daniel, but the man has been busy and he's got a few more to tease.

Daniel Nayeri:

It's funny, the way publishing kind of has moved, moved meaning after COVID things slowed down a little bit and some things sped up. And so a lot of the picture book stuff had slowed down and now they're all lined up, so they're all coming out in succession, which is exciting.

But I'll be doing several picture books coming up. One of them is a memory of this Ferris wheel in the desert, the storyteller, and it's very much a story within a story. So it's my story going to that man's house, and then we jump into the fairytale and the art style changes. I'm really excited about that.

And then we're doing another picture book about Persian carpets and the weaving of those. Another one that's not Persian at all, it's almost a little bit like a Legend of Zelda kind of vibe, it's actually a picture book that's entirely a palindrome visually.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh really?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, the boy goes down into this, he starts he's in the dark woods and then goes, and he's going down further and further into these landscapes and places until final dungeons, decrepit castle, where he comes across this monster that he's been fearing this whole time. And then he goes back up and the whole book is a perfect palindrome. So you could take the middle pages, hold them up and look at each of the two paired spreads and they go forward and backward. And it was a real puzzle-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That's awesome.

Daniel Nayeri:

... to put together.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I was going to say, how'd you write that?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah. It's called Drawn Onward, which is itself a palindrome.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Now, we've talked a lot about storytelling, the purpose of storytelling, and why it's important to make the cliche or overdone interesting again. That's something that Daniel has been thinking a lot about recently. So much so that he has another upcoming project dissecting just that.

Daniel Nayeri:

I have a book coming out called How to Tell a Story. It's actually a revision of a project I had done that was really interactive with blocks and for kids. And someone had said, "Have you ever thought about writing a How to Tell a Story just for a general audience, for adults as just a book?" And I said, "No, but that's a great idea." So I've been working on that, and nonfiction about storytelling has been fun.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, that seems it probably gives you a very different perspective on thinking about how you think about an analytical lens and how you're thinking about storytelling, instead of a different view.

Daniel Nayeri:

And it's really hard to answer this question. This is a question I've always wanted to try to answer, how to be interesting. How does anything be interesting, is one of those, you can either become very abstract when you say something like that, or you can become really specific and formal.

So, you'll see some storytelling books and they're like, "Well, how to be interesting is to follow three act structure and you have to follow this template and this." Or they'll say stuff that's really sort of broad. And trying to answer that question without limiting the writer, or the reader in this case who's wanting to be a writer, how do you make sure you're not just being one of these people who's pitching a formula, while at the same time offering something tangible that's like, let us explore how to tell something in an interesting way. That was a proper difficult challenge.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yes, it was. Okay. Lastly, I know you're working on something else that's far outside the realm of picture books or books, period. Can you tell me about your endeavor on the big screen?

Daniel Nayeri:

Yeah, I'm working on, I just finished a feature film I wrote that may be coming out early next year called Reentry. It's a sci-fi romance about a woman whose husband is an ex-astronaut and he gets recruited to be the first to walk through this dimensional port way. It's like the early days of multiverse theory. We've got all kinds of multiverse movies. This is like, "We need a Neil Armstrong, you're going to walk through, it'll be 10 seconds, it'll be no problem and then you'll be back home."

And she says to him, "Don't do it. I have a really horrible feeling about this." And he sort of brushes it off, to his own chagrin, because the movie begins with her watching as he's about to step through T-minus five seconds, he steps through, he disappears. So the music comes on, this is the very beginning of the movie, and we watch her have to go to his funeral and mourn him and put her life back together over the course of a year.

And as the year comes to a close and as the song comes to an end, we flip back to the lab, the lights come back on and he walks right back through the door. And so for him, it's been 10 seconds, and for her it's been the worst year of her life. And the rest is the sort of marriage story about what do you do when you have had that kind of rift between you?

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You wrote the film?

Daniel Nayeri:

I was the writer and producer.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

And you have this production company now?

Daniel Nayeri:

That's right. And it's called PlotNaut, which is P-L-O-T-N-A-U-T, and it's doing that film next year and two books, and we're publishing books and film and TV at the same time. So yeah, I'm really excited about the venture. We'll see how it goes. Films are very, very different.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

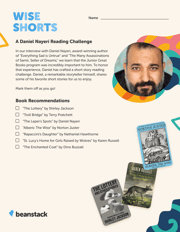

For his reading challenge, Wise Shorts, Daniel takes inspiration from his earlier reading of Alberic the Wise. Despite the story's brevity, it had a lasting effect on Daniel. And now, with our work and life load in mind, he challenges us to explore the power of words in a nice, concise format.

Daniel Nayeri:

The easiest thing to get a group of people to read, because you go to any book club, and I'm telling you, there's three people who are pretending, they're trying to look at the book while you're talking and you're like, "You didn't read this. I know you didn't read this, and now you're trying to catch up while we're in the book club and it's unacceptable." I've been in that seat before.

Yeah, so I went with the short stories, short stories I think are really interesting to discuss. Obviously, Alberic the Wise by Norton Juster is on the list, but the greatest American short story writer, Shirley Jackson, she's got to be on the list. There's all kinds of them.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Today's Beanstack-featured librarian is one of my closest friends growing up, Nikki Hayter. She's the library manager at the Franklin Avenue Library in Des Moines, Iowa, my hometown. Nikki tells us about a program that highlights the deep impact libraries have on their communities.

Nikki Hayter:

One of the services that we've recently started to provide, because there is such a food insecurity issue in our community, is we have a community fridge that is accessible to the public when the library is open. There is a merchandiser fridge and a pantry that we stock through donations. And also, we have some pretty phenomenal relationships with agencies in the community that do food recovery. It'll be a year in December, and it's been kind of mind-blowing to see the response. It's also been probably, I think one of the things that we've done recently that's closest to the parts of our staff because they see the impact.

But one of the other things we've been doing, is we've been getting out to all of the second grade classrooms in our service area just to spread the love of reading, to engage with kids and teachers, and really just support teachers as well. One of the things Miss Erica, our outreach librarian, does is when she's in that classroom is she mentions the fridge.

We know that kids talk about what they hear at school and what they learn at school with their families and so it's just another way to spread awareness. And she has been amazed at how many children have raised their hands and said, "We use the fridge." No stigma just, "We come after school on this, this, and this day," but we know that kids can't learn if they're hungry.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture, and you've been listening to our conversation with Daniel Nayeri. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and currently I'm reading Amina's Voice by Heena Kahn, and Monsters: A Fan's Dilemma by Claire Dederer.

If you've enjoyed today's episode, please show some love and give us a five star review. It just takes a second and it really helps. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com. And remember to sign up for our newsletter at thereadingculturepod.com/newsletter for special offers and bonus content.

This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media, and script edited by Josia Lamberto-Egan. Thanks for joining and keep reading.