About this episode

Angeline Boulley was born into story-telling people. As a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians was first introduced to the art through generational oral tradition. Yet during her childhood, Angeline struggled with her biracial indigenous identity. In searching for representation through the stories in books she was reading, she realized that the examples she found lacked depth and true experience.

"I think there's recognition that publishing is better the more voices are heard, and the more diverse those rooms can be as well –that it's not just a matter of changing the skin tone of a character, it's that culture is all these things that are seen and unseen, and it's in your world building." - Angeline Boulley

It wasn’t until her mid-forties that she realized she could write her own experience into existence. For nearly three decades, Angeline had mulled over a story idea, until she decided it was time to write this story. After another decade of working full-time (like really full-time as a mom of three with a big-time DC job) and seeking out time to write, she debuted with her award-winning novel, “Firekeeper’s Daughter.”

In this episode, Angeline explores her long journey to becoming an author and the themes in her latest work, “Warrior Girl Unearthed.” As Angeline says, it is time for a reckoning with the inhumane treatment of indigenous people’s remains still not repatriated throughout the United States. She shares how writing about her relationship to her culture helped her uncover her true identity and her goal to provide younger generations with authentic ideas of indigenous culture.

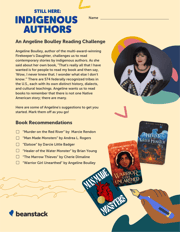

For her reading challenge, 'Still Here', Angeline encourages readers to explore contemporary indigenous writers. While reading these modern stories, she challenges us to compare and contrast what has been taught previously about native cultures. I invite you to check it out, and for Beanstack clients, use the challenge on your site! Reading challenges are always available at thereadingculturepod.com.

In this episode, we’re changing things up for our Beanstack featured librarian. Today we give the mic to Lessa Kananiʻopua Pelayo-Lozada, the current American Library Association president, to share more about the upcoming ALA conference and exhibition. Zoobean has proudly participated in ALA exhibitions for the last eight years!

Contents

- Chapter 1 - Over the horizon

- Chapter 2 - Summers in Sault Ste. Marie

- Chapter 3 - Stranger With My Face

- Chapter 4 - The Fire behind “Firekeeper's Daughter”

- Chapter 5 - We Want Our Ancestors Back

- Chapter 6 - A Collection of Scalps

- Chapter 7 - The weight of educating others

- Chapter 8 - Casting Call

- Chapter 9 - Reading Challenge

- Chapter 10 - Beanstack Featured Librarian

Author Reading Challenge

Download the free reading challenge worksheet, or view the challenge materials on our helpdesk. .

.

Links:

I want to acknowledge that this podcast was recorded on the ancestral lands of the Nacotchtank and the Piscataway people. I invite you to reflect on the complex histories of violence, displacement, migration, and settlements that have intertwined to shape this land.

Angeline Boulley:

I love my community and I think you can only write about it if you love it, because I do tear apart tribal council leaders. We have unpleasant truths in our community, but I know where to draw that line and I know that my community is more than our trauma.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

As a writer, Angeline Boulley was a late bloomer, publishing her first novel, the New York Times Best-Selling Firekeeper's Daughter in her early 50s, but the sudden acclaim didn't surprise her. As she'll tell us, she believed from childhood that she would achieve something special, and she knew that she had real truth and authentic feelings to convey, not only joy and reverence, but also deep anger at injustice.

Angeline Boulley:

I wanted to share my outrage. I love teens because that awakening consciousness, that awareness that this is so wrong.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Angeline described the interview you're about to hear as two friends catching up over wine. So, join us on my virtual porch to hear about her journey to recovering her indigenous heritage, her call for historical reckoning, and how Angeline's latest protagonist was inspired by Laura Croft. Yes, that Laura Croft with the hobby of desecrating indigenous burial sites for money. I promise it all makes sense when Angeline tells it. My name is Jordan Lloyd Bookey, and this is The Reading Culture, a show where we speak with authors and reading enthusiasts to explore ways to build a stronger culture of reading in our communities.

We dive into their personal experiences, their inspirations, and why their stories and ideas motivate kids to read more. Also, a quick reminder to check out The Reading Culture on Instagram, @TheReadingCulturePod for extra content from our authors and to participate in some very awesome giveaways. All right. Onto the show. All right. Your lipstick's applied. We're ready.

Angeline Boulley:

I know, but I always feel better when I have lipstick on. [foreign language 00:02:28]. Hello, my name is Angeline Boulley. I am Bear Clan, and I am from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, which is also known as the place of the rapids.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Thank you. Do you or have you ever gone by a name other than Angeline?

Angeline Boulley:

Family and very old friends call me Sue, Susie. My first name was Susan and I never liked it. I loved it when my mother would call me by my middle name Angeline. So, I liked it so much that I told her, "When I go away to college, I'm going to start going by Angeline." She was like, "You can't do that." I said, "Oh, yeah, I can. I looked into it. Legally, I can change my name." She was just really blown away by it, but I just chose my middle name as my name, because it felt like a really special name. I guess I just have always dreamed big and felt like there was something special on the horizon.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

What were you like as a kid? You lived in the same town you live in now.

Angeline Boulley:

Yes, yes, it's a block away. So, I was quiet, not confident at all. I was a voracious reader and I was also pretty sturdy, big-boned and athletic, but I think that having a younger sister who was very petite and beautiful in this very elegant way, I felt like an ogre next to her. So, that really did shape my confidence. I think I was always trying to be this grander, greater version of myself. So, I think at a certain point, I just realized that as long as I was trying to be someone else, I would always be a runner up to that. But if I could just embrace who I truly am, that I was worthy and I could embrace life and everything that I bring to the table, that I could just have a great journey.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When you were younger, you said you were a voracious reader. What kind of stuff did you like to read?

Angeline Boulley:

Obviously, I did read all of the Nancy Drew, all the classic mysteries, but my mom didn't drive having grown up in Chicago and my dad was a truck driver. So, he would be gone. Every Saturday, my mom, we would be like a mama duck in our ducklings. We'd walk single file and we'd go to the public library every Saturday. We'd each have our little tote bags and we could check out whatever books we wanted, anything we wanted as long as we were willing to haul it back a mile walk back to our house. So, I do remember checking out historical fiction and these gothic romance mysteries. Even as a young child, I also remember checking out books about roses, English royalty, architecture. So, I love that my parents... My father left school after eighth grade and he is like the most well-read person that I know.

So, I just love that my parents inspired this love of reading and that they embraced the freedom to choose whatever we wanted to read. There were no restrictions. I just think that's a foundation of respect. If a book is too advanced for a child, they're going to get bored. They're going to set it aside. It's why you can reread a favorite book from your childhood and as an adult reading it, see that there is so much that you missed that went over your head. Our brains, I believe, do protect us from things that we're not developmentally ready for. So, I do believe in freedom to read.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Your dad is indigenous and your mom is not and you were, but you grew up in a town that was on Native Lands. It's not in a reservation. So, did you go back and forth a lot as a kid? Because you write so beautifully, I mean, the Firekeeper's Daughter, of course, but then I've just been reading Warrior Girl Unearthed, which I really want to talk about it without spoiling anything, but just with such dexterity and at all ages of all people. So, did you grow up back and forth?

Angeline Boulley:

Growing up in the town that I did, I thought we were the only native family in town. So, what people thought about Native Americans was what they thought about the Boulley family. My siblings and I, we all played sports, just Cub Scouts, Girl Scouts. My mom was a den mother, on the PTA.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Model citizens.

Angeline Boulley:

Every summer, we would spend time in Sault Ste. Marie and on Sugar Island. My grandparents lived in Sault Ste. Marie, and they had a shack really on Sugar Island. It was where my dad was born, and we would spend time there. My dad would take us up there and then he would leave and go back to work. My mom and my siblings and I would stay on Sugar Island with grandparents and cousins. I just remember realizing that when my cousins talked about school, they weren't having the same experience that I did. I also made the connection that the darker their skin color was, the more awful their experiences were. So, that really did shape my identity.

Now, I recognize it as privilege. I have my father's features, but I'm very light-skinned. But for me growing up, there was a bit of an identity crisis like, "Wait, am I Ojibwe enough because I'm not going through the things that my cousins are necessarily going through? Does that mean I'm not as native as they are?" That was my experience growing up is always having a connection to the land, to the family, and some traditions. It wasn't until I was in my 20s where I just really became empowered like I am Ojibwe and however I am, that's Ojibwe. So, really claiming your identity and finding your place in the world, which is very much a young adult theme, which is why although I have written drafts of Firekeeper's Daughter that were not young adult-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, really? That's interesting. I didn't know that.

Angeline Boulley:

Yeah, some earlier drafts were not young adult. I knew that with the themes that were coming through in the story that yes, it was very much young adult.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When you were younger with your cousins and everything, I guess one of the things I've been thinking a lot about right now especially in just reading your books is around just the importance of storytelling and oral tradition. That seems like your dad also maintains a lot of traditions we were just talking about. Do you have a lot of memories of that and did that shape you as a storyteller?

Angeline Boulley:

I always knew that there were people in my family who were just inherently funny or could tell a really great story. Now, I know we indigenous people have always had great storytellers. We just weren't getting the book deals. So, I come from storytellers. My dad is one. My namesake, Angeline Williams, she was a storyteller.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Are there any stories that you would want to share outside of your family and people that you remember or that stayed with you?

Angeline Boulley:

I remember that when I was growing up, I was afraid of thunderstorms and then my Ojibwe grandma, my nokomis, she was visiting us one time. There was this storm coming through and it was daytime. My dad was home and she wanted my dad to put the garage door up. We had a little single car garage and my grandma wanted to sit in a chair at that open garage bay and just watch this thunderstorm just roll through, lightning and thunder. I loved my grandma so much that I wanted to spend time with her even though I was petrified of lightning and thunder. So, I sat with her and then she told me about thunder beings and how we come from the thunder and that our family is connected to it. Thunder beings are these huge birds.

When they blink their eyes, that's the lightning. When they rustle their wings, flap their wings, that's the thunder. Our ancestors travel on those thunder beings to check on us. So, every time there's a thunder and lightning storm, now I think of it's my ancestors coming to visit and check on me. I included a little of that story in Firekeeper's Daughter and had it be Daunis relaying it to Jamie about yelling back up to the storm, "We're okay, we're doing good here."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

That makes sense now.

Angeline Boulley:

I am adopted, aren't I? Tell me. Yes. Mother started to get to her feet, her arms reaching out for me, but I motioned her back. You've lied to me. For 17 years, you've lied. "That's not so," Mother said, "We've never lied. We simply didn't tell you. Why should we? You're our child just as much as your brother and sister. We couldn't love you more if I'd carried you in my body. There never seemed to be any reason to set you to wondering and worrying over things that should have no bearing in your life. Let's go downstairs now, Laurie. Your father can explain it all better than I can."

So, we went down and she got dad out of his office and we sat at the kitchen table, which is where talks in our family are always held. He told me the story. He did not seem as shaken up as mother. It was as though he had been anticipating this moment for a long time. "I always figured someday we'd have to go through this with you," he said, "someday something would come up, a need for medical history maybe, and you couldn't keep thinking your genes were coming straight down the line from the Strattons and the Comptons."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Lois Duncan's 1981 novel Stranger with My Face follows Laurie Stratton, an indigenous teen who discovers she's adopted when her secret twin sister contacts her through astral projection. The story, which is a horror, takes a fantastical turn when Laurie's twin sister takes control of her body. Laurie then has to find her way back into her own body and a parent analogy for finding and accepting this lost part of herself after the discovery of her true identity. The novel was released just a few years after the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978, which was in direct response to the life altering abuse and neglect being inflicted on indigenous children being taken from their families and put into non-indigenous homes.

But while the novel was widely praised and the themes were in some ways healing, Lois Duncan was not herself indigenous. So, although Angeline was excited to finally read a story with the main character who shared many parts of her own identity, certain descriptions and characterizations felt exclusionary and racially insensitive.

Angeline Boulley:

This story, I think I was so excited when I first started to read it. I was like, "Oh, my God. This is really cool." But then once I got into it, I had different uncomfortable moments while I was reading that I didn't have the words to explain or the words to know that it was appropriated culture, or actually, it was like misrepresentations of culture. For example, there's a part where she describes her looks and her father is a writer. He refers to her eyes as alien eyes because he writes science fiction.

So, he would always draw his characters in the stories like they would all have these almond shaped upturned eyes the way she did. I know that again, the intention was that his daughter's eyes were beautiful and he viewed them as exotic. So, in his language, he would say alien. But as an indigenous person reading the book and having them refer to as alien, it hits a little differently.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's fascinating because this book on the one hand is the first time you saw more literally because the girl is herself also mixed, but that was your first experience of reading a book where you should have seen yourself reflected where I guess by in some way you did, but it was also a moment of seeing this inaccurate, insensitive way that you were being represented.

Angeline Boulley:

Yes, and I just knew that I felt uncomfortable and I just didn't have the words though to put to it until I was older.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

When Angeline was in high school, she had an experience straight out of a movie, when a peer at a nearby school, one with whom she was supposed to be set up by the way, turned out to be an undercover cop. The story stuck with her for decades, but it wasn't until her mid-40s that she figured out how and why to tell it. Angeline used the experience as a jumping off point to write Firekeeper's Daughter, a Nancy Drew meets 21 Jump Street, her words, style novel where she shares the intricacies of growing up biracial and indigenous, sourcing many of her own firsthand accounts.

She worked on that story for 10 years, finding pockets of time to write while balancing her career as the Director of the Office of Indian Education for the US Department of Education and raising three children. The book finally hit the shelves in 2021, and the novel was met with major success, topping bestseller list, winning the Walter Dean Myers Award, the Prince Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature, and various others. The Obama's production company even purchased the rights to adapt the novel for TV. Time Magazine also named it one of the Best 100 Young Adult Books of All Time. Quite a feat for a debut novel. I asked Angeline why she thinks it resonates so well with readers.

Angeline Boulley:

I think that the attention and recognition that telling a story about a biracial mixed heritage teen told from the perspective of someone who is that and knows the nuance of it. I think publishing has come to a reckoning that publishing is so overwhelmingly White that if you have the same type of people making decisions at every level, because publishing isn't just a one-time yes, you don't just get an agent and then you have a book deal. It's like your manuscript is being discussed in many different rooms. If they are all filled with people from similar backgrounds, which publishing is notorious for because there's the belief that "Oh, you have to live in New York and pay your dues with these unpaid internships."

Well, we know that like breeds like. People that get a leg up in the industry are people who have these advantages. I think there's recognition that publishing is better and more voices are heard, the more diverse those rooms can be as well, and that it's not just a matter of changing the skin tone of a character. Culture is all these things that are seen and unseen and it's in your world building. So, I think I happen to come along at the right time when publishing was hungry for a mystery thriller featuring a strong Native American protagonist set on an Indian reservation and written by someone who could write the nuance and go beneath the surface and do so in a way that did not perpetuate stereotypes.

I love my community and I think you can only write about it if you love it, because I do tear apart tribal council leaders. We have unpleasant truths in our community, but I know where to draw that line and I know that my community is more than our trauma. So, the humor, the role of elders, all of these wonderful things that I feel like someone outside of my community trying to tell a story about my community would only see the surface and the story that you would get would be just veneer and it would never get the depth and nuance and authenticity that I can tell a story about my community.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

It's so true. I have to say that after reading your latest book, Warrior Girl Unearthed, I was like, "Oh, my God. This woman is just getting started." I was particularly fascinated by the quote markers throughout the book and realized that they all are actual non-fiction sources and it just makes this story have such a strong educational aspect to it, but at the same time, it's like an absolute page turner. So, you've done an amazing job at imparting knowledge but also keeping it very fun and intriguing. Yeah. Can you tell me more about the story and also just how you've done that so effectively?

Angeline Boulley:

So Perry Firekeeper-Birch is a 16-year-old teen and she intends for her summer before her junior year to be nothing except Perry's summer of slack. She just wants to spend the summer helping her dad in his garden and wants to be fishing and playing with cousins. She encounters a bear in the road and loses a game of chicken with that bear and has to pay back her Auntie Daunis for these Jeep repairs. So, she is forced to take the very last opening in the tribe's summer internship program. She'll be paid a wage and has to work in the tribal museum with this guy they call Kooky, Cooper Turtle. She doesn't want to be there, but he ends up taking her to a local museum, a local college that has a museum. She sees that museums have in their collections, in their archives ancestral remains.

So, they have bones and skulls and teeth that were from grave robbers donated by collectors, all different ways that museums get these items that are ancestors' bones and sacred items that were buried with them. There is a federal law called the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, and that law says museums are to inventory their collection. If there are tribes that believe that their ancestors are part of those collections, they should be able to get those returned to them. Despite there being a law, there's so much heel dragging and delays and loopholes.

Perry is outraged and she decides she's going to be like this indigenous Lara Croft and take matters into her own hands. Each section of the 10-week internship starts with an epigraph and those epigraphs aren't part of the story. Therefore, the reader, because some of the quotes take place after the story took place. So, they are for the reader, not for the story, but they are all actual letters, transcriptions, accounts of ancestral remains and the way in which they are treated.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Are those the 10 books on the list that Mr. Cooper gives her?

Angeline Boulley:

Many of them are, but there are some, like Shannon O'Loughlin is the executive director of the Association on American Indian Affairs. They're the largest oldest nonprofit and she wrote a letter to Harvard saying, "You have more-"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Oh, God. That is like the beast letter.

Angeline Boulley:

Yes. She's like, "You have more deceased native bodies in your museum archives than you have native people on campus. We want our ancestors back."

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

I was like, "Put this woman on a stage."

Angeline Boulley:

Yes.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Through this educational aspect of the novel, Angeline draws attention to the ongoing issue of disrespect for indigenous remains, including the theft and exploitation of remains for scientific research in museum collections. The 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was meant to address this issue, but many challenges still exist in implementing the law and respecting native sovereignty over their cultural heritage. This is an issue that Angeline has a strong emotional attachment to, and her personal experiences have directly informed Warrior Girl Unearthed.

Angeline Boulley:

I spent September of last year, two weeks in Paris and two weeks in Germany, four different cities in Germany. I attended two different international literary book festivals. I took a side trip to Dresden, Germany, because there is a German author, Karl May, who wrote a character that is native and very stereotypical and he's also a collector. So, there's a Karl May Museum where he actually displays scalps-

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Collector. You mean like... Oh, oh.

Angeline Boulley:

Collecting ancestral remains. So, I was like, "Okay, this is book research." You can bet I'm deducting my stay in Dresden. I wanted to see for myself if the Karl May Museum was as awful as I had heard it to be, and it was. People believing that they're honoring Native Americans or they fetishize and love Native Americans, but the ways in which they express that love, if you have scalps and skeletons in your museum on display, that is not honoring. To honor our ancestors is to return them when asked so that we can give a proper reburial.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, you really felt that in the book. Oh, first of all, I remember reading, which I didn't know about something in the book about in Denver, I think it was a Denver opera house maybe. You were referencing how there were remains basically hanging up.

Angeline Boulley:

It's very graphic. Yeah. Some of these historical accounts that I used as epigraphs, I was outraged to read it and I was like, "Wait, they strung what body parts of women?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Pubic hair, is it?

Angeline Boulley:

Scalps but of your private parts of indigenous women and they were strung across a theater stage.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Disgusting.

Angeline Boulley:

The callous disregard and disrespect and inhumane treatment of indigenous people, living and dead. I think that's a reckoning our country is overdue for.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yeah, I could not agree more. That's a very heavy thing for you to be taking on and just trying to educate a lot of people about this issue. Do you feel that weight, especially now that your book Firekeeper's Daughter and hopefully Warrior Girl Unearthed has become so popular or is it something that you just really embrace?

Angeline Boulley:

I'm outraged that there are more ancestors that have not been returned since NAGPRA was passed than have been. There are 108,000 ancestors still in museum collections. We're talking Berkeley, Harvard. There are more of our ancestors there than have been returned back to the tribes that are requesting them. I wanted to share my outrage and I love teens, because that awakening consciousness, that awareness that this is so wrong and Perry was just the perfect narrator for this and for the reader to be right there beside Perry and feeling her outrage and her call to activism.

For example, the day that we're recording this, Wisconsin had their Supreme Court election and it galvanized so many young voters voting for the first time to vote overwhelmingly for a candidate that is pro-choice or is of the party that is protecting bodily autonomy. I think I want to do whatever I can to speak to those teens that I hear you, we need your voice and your energy and your don't give an F.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right.

Angeline Boulley:

I love it.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Yes, I love that energy too. I know the teens, they love you. So, I'm curious about your experiences visiting them, visiting schools. I know you have a lot of readers who are not indigenous themselves, so what do you hear from the students that you visit?

Angeline Boulley:

The author James Joyce wrote, "In the particular, we find the universal." I see that experience happening in the school visits that I do with students who say, "This is the first time I ever saw myself in a book." They're not even native, but being biracial, feeling like they don't fit in or have to code switch. I think Angie Thomas did so much with The Hate U Give to introduce a wider audience to yes, that's called code switching and this is what you do. Garden Heights star is very different than private school star.

When I hear a student say that they never read a story like mine, they never rushed to finish a story or stay up late reading it, I think that's one of my favorite things that I hear is when a teacher says a reluctant reader or a student who struggles to finish reading assignments that they zipped through my book and had so much to say about it. I love that and I love that for all of the work that I did in Indian education, even at the national level, I was the Director for the Office of Indian Education at US Department of Education, that even at that national level, the power of a story to share, teach, show lives different from our own and for students who have never read a story about a modern native protagonist and to learn all of these things.

I talk about skin color, I talk about casinos, I talk about pro capita. I talk about all these different things and I think I'm able to educate more people through the pages of a story and characters that they care about than I ever could at that federal level.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Do you have a favorite school visit you've ever done?

Angeline Boulley:

There was one school visit and it cracks me out, because sometimes at a school, they will vet the questions. So, they'll have students write their questions on index cards. They vet them and then they curate the questions that are going to get asked of me. At this one school, they didn't. I honestly prefer unvetted questions. This young man, after I get done talking about my journey, my path to publication and what's next, and he said, "Can you get me a part in the Netflix series?" I just cracked up and I was like, "Oh, what part do you think you should play?" He said, "Oh, I don't know. I didn't read the book." Yeah, I just thought he was so funny.

I said, "Well, come up to the stage afterwards. I'm going to give you my business card. You read my book. When you finish, you reach out to me and let me know what part you think you should play and what part you think you are so not suited for." I have yet to hear from him. But I just loved that whole refreshing like, "Hey, get me a part," and then me being humbled by the guy didn't even read the book.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Right. Their ears perked up Netflix like, "I'm listening."

Angeline Boulley:

Yeah.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

But hey, that's going to be... We're all waiting for that.

Angeline Boulley:

Miigwech, thank you. Chi-miigwech, big thank you for having me on the podcast and just thank you so much for this opportunity. It was so good talking with you.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Angeline's work is meant to open eyes across America and really around the world to the treatment and experience of indigenous cultures, but she also wants readers to understand that one culture does not represent the hundreds across this country. Angeline is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie tribe of Chippewa Indians. That experience shapes her perspective. So, for her reading challenge, she wants readers to open themselves up to other contemporary indigenous writers.

Angeline Boulley:

I challenge readers to read another indigenous author and contemporary story, not a story set in the past. I want readers to read more indigenous stories from indigenous storytellers and compare and contrast. As an educator, that's what you want your students to do and to start thinking about, "Why didn't I know this history? Why didn't I know this before?"

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

You can check out Angeline's challenge and all of our author reading challenges at thereadingculturepod.com. Typically, at this point in the podcast, we feature a Beanstack librarian doing awesome work in their community, but today, we have the honor of welcoming Lessa Kanani'opua Pelayo-Lozada, the current American Librarian Association President, to share a bit about the upcoming ALA conference and exhibition.

We, my company Beanstack has exhibited at ALA for the last seven years, and it's always such a joy to connect with our clients and to participate in a lot of the incredible programming that they offer. You can check out this year's program and the speaker lineup at 2023.alaannualconference.org. I think in person is best, but there is actually also a really awesome digital experience available that you can check out at that site. Here's Lessa telling us a bit about the conference and what to expect this year.

Lessa Kanani'opua Pelayo-Lozada:

So our annual conference this year is in our hometown of Chicago. We are so happy to be returning home. It's going to be June 22nd through the 27th. As the world's largest and most comprehensive library event, ALA of course brings together thousands of librarians, library staff, educators, authors, publishers, friends of libraries, trustees, special guest exhibitors, and of course, library lovers into one space. One of my favorite parts about annual conference is being surrounded by all of the amazing literary lovers in addition to the library lovers.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

Honestly, if you love books, which you probably do if you're listening to this podcast, then ALA Annual is just a really neat place to be because there are so many authors in attendance. I also ask Lessa about what some of the themes of the conference will be this year.

Lessa Kanani'opua Pelayo-Lozada:

At this conference, we will of course be discussing intellectual freedom and the right to read. We'll also be talking a lot about digital equity and what our digital life looks like in a post-COVID world. We're also going to focus on leadership and innovation in libraries. Through all of the change that we've been through over the last few years, we need strong leaders now more than ever. In relationship to that, we are also going to be talking about health and wellness and the trauma that we've all experienced and how we can move forward as library professionals and library lovers to be able to support and help our communities.

Some other really important topics that we're going to be discussing are small and rural libraries and all of the opportunities that are happening in those areas, as well as the challenges and how we can look towards digital equity and connecting that with our small and rural libraries as well as prison libraries. Our folks have been doing a lot of work on updating the standards for prison libraries. So, those will be coming forward at our annual conference to really set the stage in a historic moment for those who are incarcerated.

Jordan Lloyd Bookey:

This has been The Reading Culture and you've been listening to our conversation with Angeline Boulley. Again, I'm your host, Jordan Lloyd Bookey. Currently, I'm reading Before The Ever After by Jacqueline Woodson and This Other Eden by Paul Harding. If you enjoy today's show, please show some love and rate, subscribe, and share The Reading Culture among your friends and networks. To learn more about how you can help grow your community's reading culture, you can check out all of our resources at beanstack.com and join us on social media at The Reading Culture Pod.

Be sure to check out The Children's Book Podcast, the teacher and librarian, Matthew Winner. It's a book podcast made for kids ages 6 to 12 that explores big ideas and the way that stories can help us feel seen, understood, and valued. You can find it wherever you listen to podcasts. This episode was produced by Jackie Lamport and Lower Street Media and script edited by Josia Lamberto-Egan. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode. Thanks for joining and keep reading.